September Staff Picks: Intern Picks!

Words By F(r)iction Staff

Eliza Browning

As autumn approaches, I’ve been enjoying listening to Lili Anolik’s podcast Once Upon a Time… at Bennington College. The podcast focuses on the intersecting lives of three literary Brat Pack writers, Donna Tartt, Bret Easton Ellis, and Jonathan Lethem, at their remote liberal arts college in the 1980s. A fictionalized version of Bennington appears prominently throughout their later works, making a closer examination of their college years critical to tracing their literary trajectories. Anolik’s extensive research and engaging voice, along with interviews with the major writers and their friends, classmates and professors, makes this a fascinating listen. The isolated setting, literary intrigue and unsolved mysteries of their shattered friendships also make this the perfect podcast for spooky season.

Sam Burt

Granted, I’m seven years late to the party but I have to say that the first season of Master of None gave me more feels than any other cultural product I’ve consumed of late. Despite my initial doubts—Ansari’s public fall from grace? A show about funny people with nice clothes and attractive New York apartments? Netflix comedy?—I loved the loose feel of the opener and was won over by the second episode, which manages to be both laugh-out-loud funny and strike a poignant note on communication difficulties within families between first- and second-generation immigrants. The characters are so well-written and acted that they make great company, but Noël Wells’ Rachel stood out for me as the love interest who manages to steal scenes even from Ansari’s Dev—their on-screen chemistry and the slow-burn unfolding of their romance felt fresh and authentic. Many have praised the show’s formal experimentation and willingness to take risks, such as the second episode’s extensive use of flashbacks and digressions to give us the backgrounds of fairly minor characters. The makers have a firm grasp of how the Netflix platform allows for narrative innovation. It’s by no means perfect—the second season drifted for me, and I think it’s fair to question the squeaky-cleanness of Dev’s character (not because of the actor’s off-screen behaviour but just because it makes him less rounded). Nevertheless I found the first season a much-needed daily caffeine boost (with extra dopamine).

Azalea Acevedo

Ever late to the hype, I’ve recently started and finished The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. It follows a young, Jewish woman, Midge, in 1950s New York who accidentally begins doing stand-up comedy after her husband leaves her for his secretary (he was not the most original man!). From seedy bar to seedy bar, her astute and sometimes crass observations of family life and social convention earn her either applause or arrest. Every episode drew me in, as even Midge’s life outside of her stand-up routine is full of comedic material. She has nosy in-laws, parents who are both nosy and astoundingly clueless, wild children and a curmudgeonly manager. The show is a brilliantly funny and irreverent look into what life in the 1950s was like for women who bucked social convention and carved their own futures.

JP Legarte

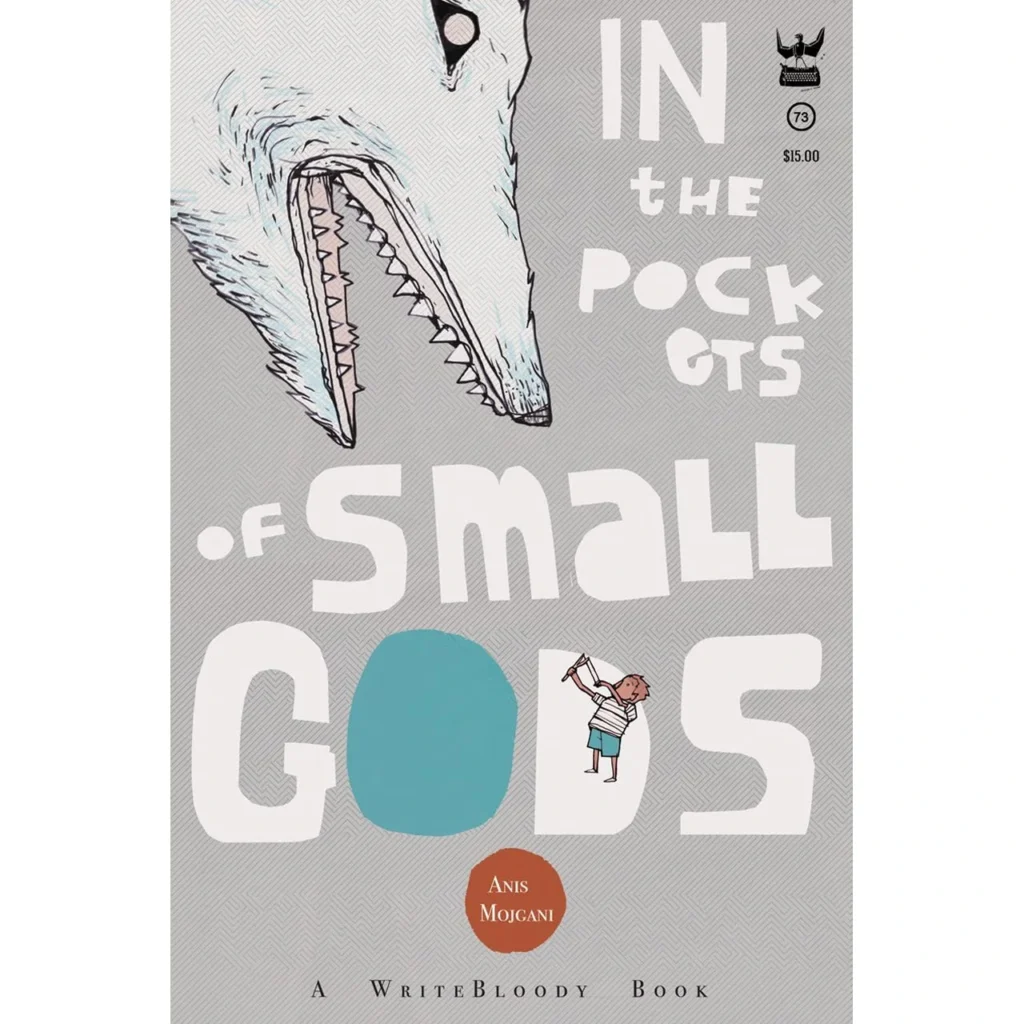

While I haven’t read many works under the genre of horror recently, I do believe that one aspect of life that is often scary as it is sudden to face and process when it arrives is grief. In my current binge of reading and exploring different poetry books, Anis Mojgani’s In the Pockets of Small Gods truly stands out for the way its poems effortlessly permit readers such a personal look into how Mojgani himself has faced and processed grief. From mentions of Greek gods and goddesses and references to the status of our very broken, complex world to thorough insight into the deaths of a friend, a marriage, and even peace and reason, readers are afforded the opportunity to process their own grief in a space filled the beauty and vividness of poetic language.

In this book, the poetic language is not firm or forced but rather flexible, almost sounding like a natural conversation at times that enhances the authenticity of what Mojgani is communicating. Yet, simultaneously, there is an appropriate softness and lull that blankets the whole book as if providing that silence to grieve while still acknowledging the hope naturally embedded in the future. Ultimately, I really admire the authenticity that shines through every poem and these worlds that Mojgani so willingly invites us into, all the while displaying the power of poetry as space for both mourning and movement into what lies ahead.

Sarah Westvik

I’ve been enjoying the recently-released The Rings of Power on Prime Video. It’s a visually stunning, musically luscious, and incredibly well-acted interpretation of the Second Age in Middle-earth, a period set thousands of years before the events of The Lord of the Rings. I choose the word “interpretation” rather than “adaptation” given the sparse material in the books that can be directly adapted, which has generated a lot of conversation about the relationship between faithfulness to source material and plain old good storytelling. For my part, I tend to privilege the latter, and I can say that anyone comfortable with doing the same will find that—beyond some teething problems with pacing—the series achieves that.

After watching my favourite realm (Númenor) and favourite characters (the eventual king Elendil and his son Isildur) come to life in ways I did not expect to see in my lifetime, I’m sold on the show’s ability to incorporate the Second Age’s themes of mortality and power through moving and complex character moments building towards both heroism and tragedy. And of course, the heroes aren’t the only thing done well—the terror and horror of the villains and the more morally uncertain characters is being chillingly realised. I always return to Tolkien because I love my fantasy full of heart with compelling characters, beautiful worldbuilding, and resonant storytelling, and Rings of Power has thus far been a much-needed return to magic.