Schadenfreude: Why We Revel in the Downfall of the Rich

Words By Hannah M, Art By George Cruikshank

Tragedy relies on a cast of characters at the pinnacle of their lives, whether that’s through wealth, fame, or social status; it’s what makes their downfall so compelling.

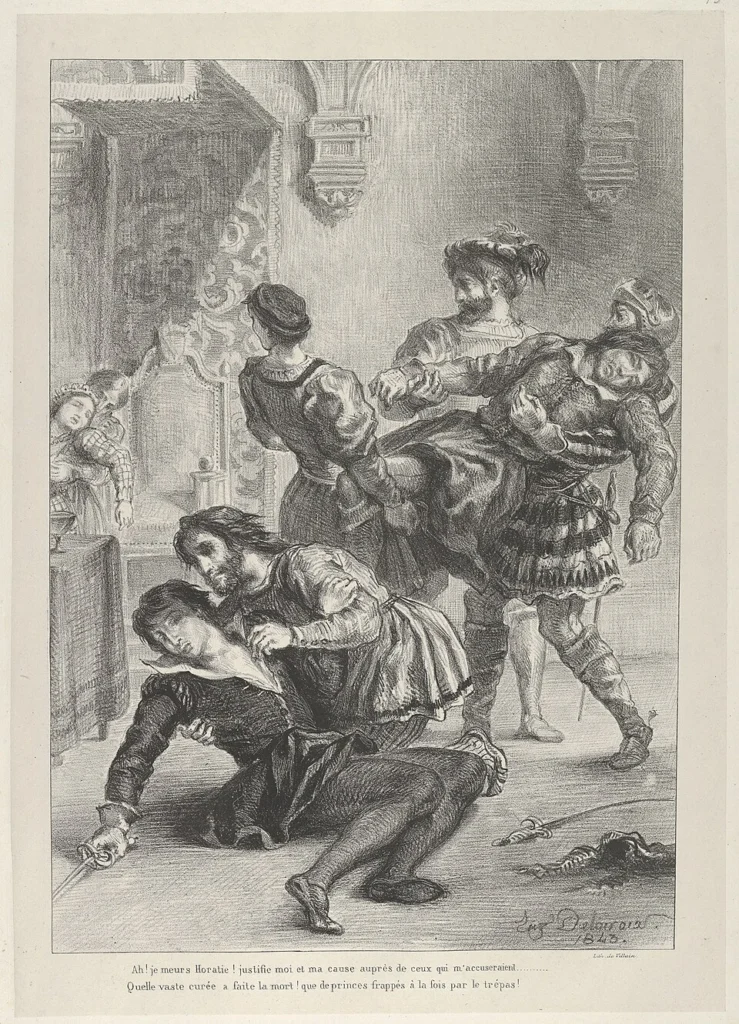

Shakespearean and Greek tragedies share a commonality with those of our time: a character’s hamartia (fatal flaw) causes their destruction, and we witness the rise and fall of a tragic hero. However, while we may sympathize and feel pathos for literary characters like Othello and Oedipus Rex, this doesn’t translate to onscreen and reality, where we relish in the downfall of the wealthy.

For the Greeks, tragedies traditionally used to serve as a morality play of sorts, warning the public of the consequences of yielding to vices. It was a caution to the everyday man, yet it now centers on the greats and serves as entertainment. Why? Because we feel that such a drastic tragedy cannot befall us; we are immune. We do not indulge in this excess wealth; therefore it cannot blind us.

We’ve reveled in the downfall of the rich since the beginning of time: from Marie Antoinette to the Redstone family. Moreover, with the ongoing crisis surrounding Rupert Murdoch and his empire, this conversation has never been more relevant. But what is it about these shows that hook us?

Why the Rich Make the Best Characters

Shakespeare wrote his plays at a time when less than 20% of the general population could read. Their everyday lives revolved around work, which was why the aristocracy and upper-class were typically the target audience for these tragedies. Since they had the money to afford such works and more free time during the day, Shakespeare wrote about them.

George Bernard Shaw said, “Hamlet’s experiences simply could not have happened to a plumber.” No one wants to see what an ordinary working-class character does in a day. Simply put, we’re nosy. We love to glimpse into the inner workings of the wealthy; what they eat, what they wear, what they do in their day-to-day lives. But it causes resentment in us.

Onscreen media like Succession, Knives Out, and The Fall of The House of Usher act as modern-day retellings of classic tragedies, often Shakespearean in tone. They possess all the typical Aristotelian tropes. The hubris, the sabotage, the greed, and deception. The generational greed of the Roy’s breeds ego, insecurity, and entitlement; the Thrombey’s unravel due to selfishness; and the Usher dynasty crumbles under the weight of their moral rot. And worst of all: they never seem to get what’s coming to them. So when we see them struggle, albeit on a different scale to the working-class, it’s satisfying. We believe their hamartia is much worse than ours, making us feel better about ourselves, or feel, in the words of the Germans, schadenfreude, our innate malevolence at seeing the misfortune of others. These characters undergo a peripeteia (reversal of fate) in a way that seems impossible in the real world. We’re entertained by the fact that money can’t buy happiness; that they suffer from the same affairs, daddy issues, and betrayals like the rest of us.

We have a “just-world” bias: we want to believe the world is just and people get what they deserve. However, it’s becoming increasingly obvious this is impossible. With billionaires evading justice, rights being stripped, and class inequalities growing, it seems like the world has gone topsy-turvy. Literature and film traditionally acted as a means of escape, and in a way, they still are. We love watching the uber-wealthy being dealt bad hands, because, for the first time, we’re not the ones suffering.

No Pathos for the Wicked

As the American Dream becomes increasingly out of reach for modern Americans, with 74% unable to save for the future, we are infuriated by the sheer and grotesque display of wealth. While so many live paycheck to paycheck, the wealthy can afford to gallivant in private jets. We’re angry at those who can indulge in such luxury while we suffer. In America, where the average family cannot sustain themselves on minimum wage, class disparity has sky rocketed. We’ve grown fatigued at the excess wealth: in 2020, viewership for Keeping Up With the Kardashians exponentially decreased to just over one million; at its peak, 4.8 million people were tuning in.

A Shift in Selective Sympathy

But why has this shift occurred, in which we are selective towards whom we feel pathos? Take Jay Gatsby, a rich literary figure who meets his downfall. Instead of feeling triumphant over his suffering, we mourn him. We don’t resent his wealth, because he is an outsider who will never be a part of the social elite no matter how hard he tries. His struggle reminds us of the rigidity of social hierarchy, and the fantasy of class mobility, proving that we don’t hate wealth—we hate unearned wealth.

This ties into one of the internet’s favorite phrases: “nepo babies.” In an age of wealth disparity, the Roy family in Succession are perhaps the most well-known example. Entitled, egotistical, and out of touch, they are not “serious people,” yet they believe they deserve control of their family business purely because of the virtue of their birth.

They hand-pick the President—a man scarily reminiscent of a certain someone in power today—demonstrating the reality of the wealthy who don’t seem to care about how decisions affect those below. When a self-made man claws to the top and is crowned, we delight in the fact that the siblings meet their downfall, losing to “one of our own,” even if he is equally conniving and wealthy.

As billionaires blast into space on the backs of exploited labor, we watch from below, angry and disillusioned. Just as Roman Roy once watched a failed space launch with casual detachment, the wealth gap is quite literally astronomical. So it’s no wonder we find comfort in the fictional lives of the wealthy onscreen. Schadenfreude is no longer seen as something shameful; we gloat as it gives us the temporary justice we desperately crave. The skyscrapers these billionaires inhabit are emblematic of how untouchable they are, making their fall all the more sweet. Are we not entertained?