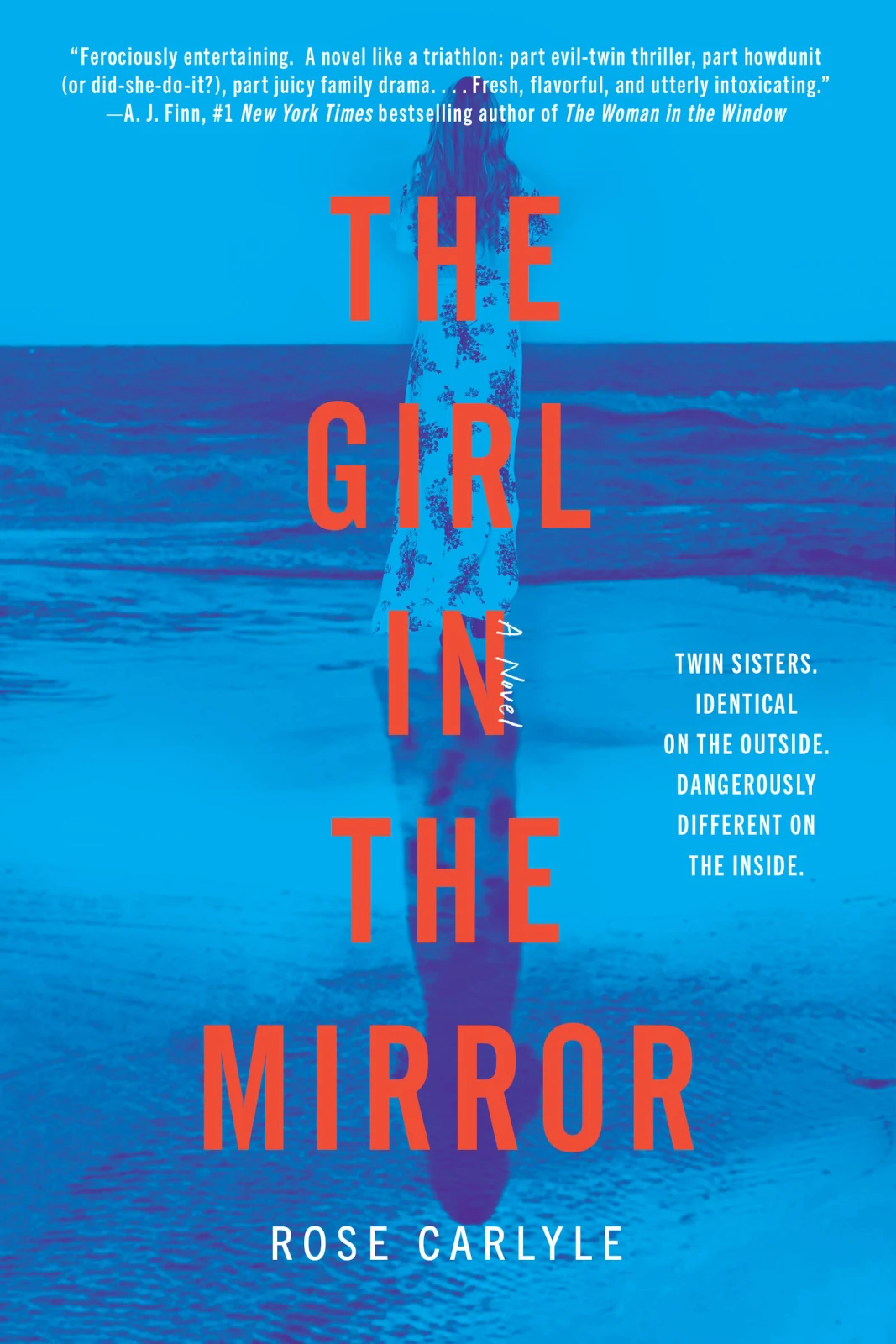

Sailing Away: A Review of The Girl in the Mirror by Rose Carlyle

Words By Cassandra Perez

Published on October 20, 2020 by William Morrow

Female-penned thrillers about bat-shit-crazy women have seen a sort of Renaissance in the last decade. From Gillian Flynn’s ubiquitous Gone Girl to Paula Hawkins’ hallmark The Girl on the Train, female rage and revenge is, well, all the rage right now. But why? Have women writers identified some deep-seated desire in suburban moms to tear their close relationships a new one? Have female audiences finally tired of the tepid, clean-cut morality offered by the works of their male counterparts? Whatever the reason is, I’m totally here for it, and welcome Rose Carlyle’s The Girl in the Mirror into the fray with open arms.

The debut thriller by the New Zealand author, The Girl in the Mirror tells the story of twenty-three-year-old twin sisters Iris and Summer Carmichael—uncannily alike on the surface, but dizzyingly different when the layers peel back. Though they are identical, Iris has always been envious of Summer and her seemingly perfect life. But when a sailing trip across the Indian Ocean goes wrong and Summer disappears, Iris finds herself stepping into her sister’s shoes. Suddenly, she has everything she coveted in her sister: her family’s prized yacht, Bathsheba; Summer’s perfect husband, Adam; and the knowledge that she’s one step closer to the hundred-million-dollar Carmichael fortune. The only problem: she needs to produce an heir before any of her step-siblings, all while navigating the mine-field of her new double life.

At first glance, The Girl in the Mirror seems to have all the elements of a saucy and successful thriller: a sibling rivalry with a sharp edge, a family inheritance with archaic stipulations, and a picture-perfect marriage fraying at the edges. Easily digestible and full of tropical flair, The Girl in the Mirror is the perfect beach read. As a narrator, Iris’s voice is intoxicating; her unapologetic-ally vain ambition and cynical outlook on life holds the reader in enraptured suspense, wondering just how far she would go to secure the Carmichael fortune. It’s a car crash you can’t look away from, in all the best ways. Her voice is emboldened by the twist, which takes your breath away, and a final line whose impact reverberates long after the book is shut.

But where The Girl in the Mirror succeeds in its intriguing premise and the potency of its female lead, it falls victim to a lack of thematic cohesion. Is it necessary for every story to have a moral? Perhaps not, and one could very well argue that its lack of morality is a function of the sphere of privilege the characters inhabit. But even after the book’s end, it’s hard to come to settle on any definitive take-away. The cut-and-dry dialogue and flat secondary characters compounds this effect. A dark current runs through the relationship between Iris and Summer, but the origins of this rift aren’t explored in full. The same stands for Iris’ relationship with her brother Ben, whose appearance is as underwhelming as it is short-lived. The illusion of Adam as the perfect husband shows signs of cracks, but stops short of showing us the full picture. In short, The Girl in the Mirror is commercially satisfying, but it fails to get to the crux of the complexity of the glittering world it creates—the intersections of pain and privilege.

The pandemic-induced social isolation sucks, which is why the escape offered by The Girl in the Mirror comes at precisely the right time. Carve out a weekend, lift the sails and dive in. Taste the sea-salt in the air, let your hair tangle in the wind that rolls off the tide, and steer your boat into uncharted waters. But don’t take your hand off the wheel— you might find yourself thrown overboard.