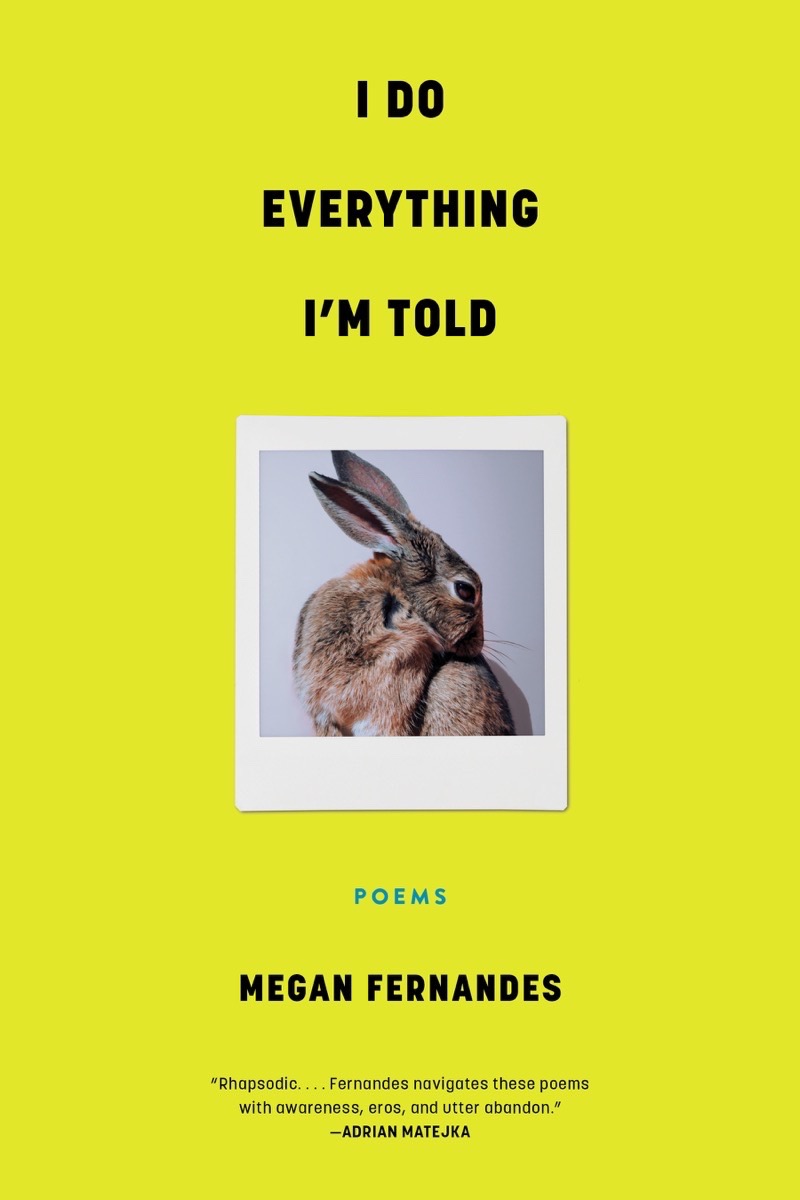

Review of I Do Everything I’m Told by Megan Fernandes

Words By Alex Schotzko

Published by TinHouse on June 20, 2023

In I Do Everything I’m Told, poet Megan Fernandes curates a sweeping photo album of a restless life—church pictures and nudes alike. Her witty nihilism feels instantly familiar and appropriate for the strange time period from which this book emerges: the suffocation of mid-pandemic isolation contending with the unmoored freedom of a re-opened world. A weary but relentless infatuation with life coats these pages, yet Fernandes stops short of any definitive conclusions—rather, she leans in and claims the questions. “Where am I supposed to be at this age?” she asks in “Phoenix.” With language as imaginative as it is casual, as funny and self-aware as it is heartbreaking, she creates a space of intimacy and approachability that I haven’t experienced in many books of poetry—one I deeply appreciated as a novice poetry reader.

Granted, when I say “approachable” here I certainly don’t mean shallow or easily understood. There were enough references to Rimbaud, Rilke, and Brooks to keep Google within grasping distance as I read—and even then, several poems still went over my head. I wouldn’t call this a “beginner” book of poetry by any means, but I also wouldn’t let that stop you from engaging with it if that’s where you fall as a reader. There is so much to be seen and felt in this book, even if you don’t know what a villanelleis or fully grasp the nuance with which Fernandes employs her heroic crown of sonnets in Part II. Even at its most formally and intellectually dazzling, this book remains a three-a.m. conversation with your slightly wine-drunk friend about the beauties and infinite frustrations of life.

And I Do Everything I’m Told has all the frankness and vulgarity you’d expect to tumble out of that wine-drunk friend’s mouth. Fernandes’s poems tote titles like “Fuckboy Villanelle,” “Get Your Shit Together and Come Home,” and “How to Have Sex in Your Thirties (or Forties).” She treks through abortion, divorce, masculinity, Catholicism, and “white girl gentrifiers / having their white girl epiphanies”—all with an egalitarian informality. There’s a sense that nothing is too sacred to probe and dissect, not even herself. “I go low some days,” she acknowledges in a poem about looking for dignity at the grocery store. At first, this “lowness” might read like simple irreverence for life, and I found a lot of joy in the chain-smoking badassery of that feeling.

But it’s more complicated than that. Fernandes contorts her poems in such a way that irreverence begins to feel like prayer. “I watch your film about fisting,” she begins a piece, before continuing several lines later: “To be taken apart is as important as being put together. / Near-annihilation reminds you of a limit / and ask yourself, who do you trust at your limit?” The sacred bleeds into the vulgar, and the vulgar often leads to revelation. Fernandes’s unkempt honesty doesn’t take away from the intimacy of this book—it multiplies it, draws you closer, and invites you to reimagine what constitutes a meaningful life. “I do not track the world by beauty but joy,” she writes in “Love Poem.” “Even if it was ugly, it was joy.”

The book itself is separated into four sections, each with different tendencies toward form and theme. While I found favorites in each, the most incredible section to me as a whole was the aforementioned Part II, “Sonnets of the False Beloveds with One Exception OR Repetition Compulsion.” It contains eight full sonnets—each named after a different city—and eight “broken” versions of those sonnets with missing words and new meaning. This gave me a sense of traveling through space and time, of uncovering loves in many different forms and places, and of feeling it all change in the fragments of memory. Now, did I have to remind myself what a crown of sonnets was? Yes. Did I have to read through this section several times to discern what was happening on the page? Yes. But my limited grasp of Fernandes’s skill and boldness didn’t stop me from being moved by her words and their form. In fact, the attention they required of me deepened their impact.

The precision of Fernandes’s imagination—and the freedom with which she releases it onto the page—creates spaces of magic and mysticism within everyday scenarios. “Space Cowboi” begins with a divorce lawyer and ends on the icy rings of Saturn; “Shanghai” begins in…well, in Shanghai, but ends in an alternate dimension where Fernandes’s “beloveds multiply, / and with them, their laughters.” I could never guess where a poem would end, and I loved the disorientation of it. It felt so cathartic, so aligned with the nonstop chaos of our post-Covid world. “Optimism plus despair // is the soup of our time,” she says in “Too Much Eliot.” And I think we all might be getting a little tired of soup.

I Do Everything I’m Told is equal parts a celebration of and formal complaint against the dirtiness of life. It’s a tome of ostensibly conflicting moods: goofy and tragic, wrathful and zen, irreverent and sacred. The best part about it, though, was realizing partway through that these moods aren’t really conflicting at all—they balance and inform each other. And even if imbalanced, “not everything / holy has to hurt or cohere.” This book reminded me that a life’s value isn’t found in control, perfection, or logic. It’s the opposite, really. “Contradictions are a sign we are from god.” And god is in the ugly, joyful thick of it.