Resurrecting the Monster Myth: An Interview with Isaac Marion

Words By Issac Marion, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

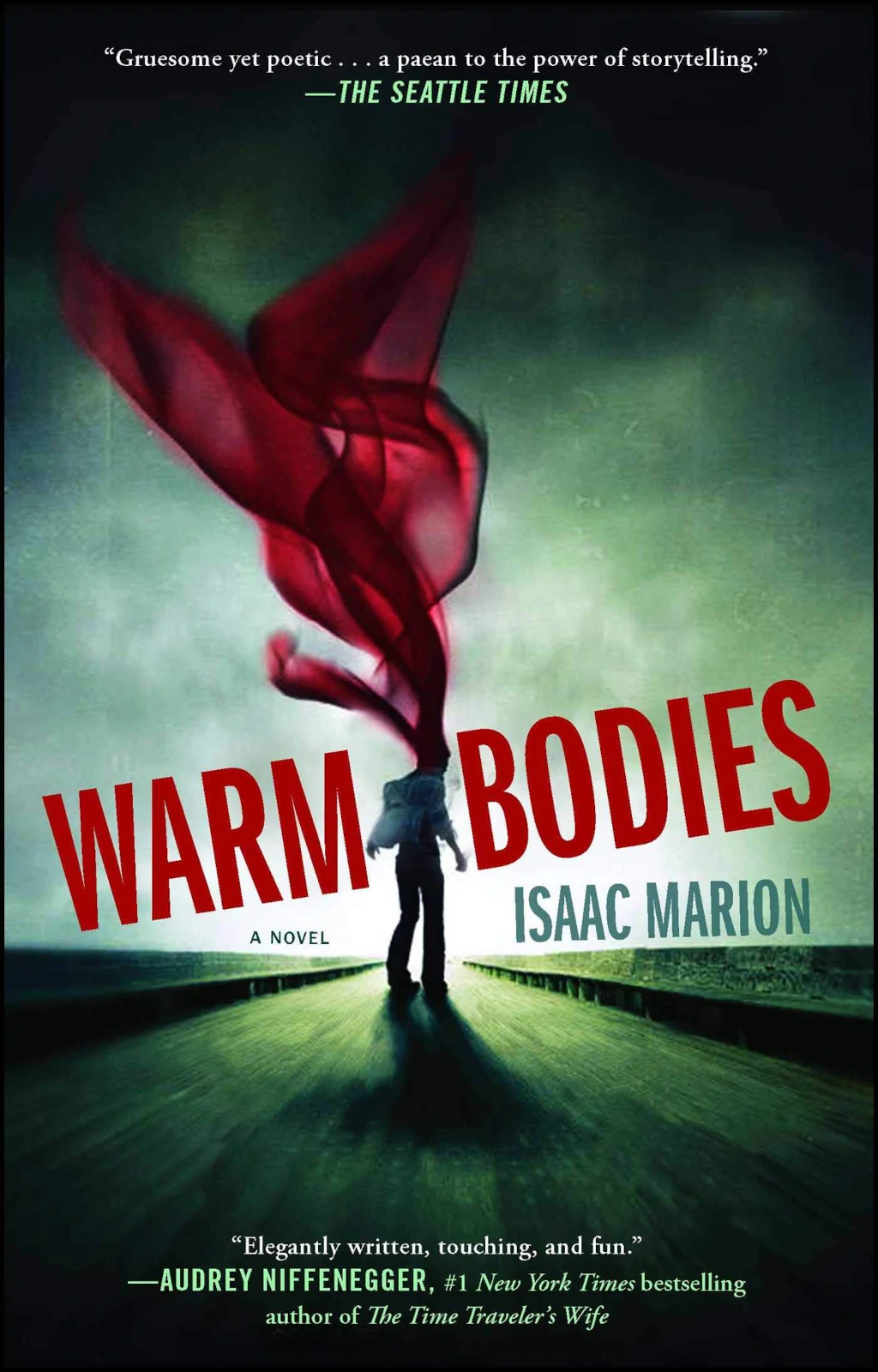

In the last ten years, the world has become obsessed with resurrecting old monsters, flooding our bookshelves and televisions with new-age vampire, zombie, and werewolf lore. Unfortunately, this frenzy has led to the production of a worrisome amount of sex-saturated and painfully campy fiction and now, the mere mention of a zombie romance will have erudite readers turning away. However, in the case of Isaac Marion’s debut novel, this would be a mistake. For instead of drowning in modern clichés, Warm Bodies defies the monster genre, creating a novel with a startling degree of emotional and intellectual ingenuity.

Through the eloquent narration of our main character, a zombie known only as “R,” we are transported into the post-outbreak world. Like all zombies, R has lost the memories of his former life, yet he mourns that loss. He hunts, kills, and decays like the undead around him, but beneath his rotting flesh, a vestige of humanity remains. When he consumes the brain of a young boy, this internal disparity is pushed to the surface, the sudden flash of memories inspiring R to protect his victim’s girlfriend, Julie. After smuggling her back to the heart of the zombie civilization, he and Julie form an unlikely alliance, one made exceedingly hilarious by R’s communication deficiencies and Julie’s caustic wit. But despite their innate differences, the two grow closer, and R must learn to distinguish his budding affections from the residual emotions of her dead lover, still clamoring for attention long after his brain has been digested.

As the lines between the living and dead begin to blur, Warm Bodies transports the reader from the strange society of zombies—one where old social programming is carried out meaninglessly—into the gated fortresses where the uninfected live. Narrating R’s delve into this world, voices of his past victims rise up like a Greek chorus to retell the origins of the zombie outbreak and how the remaining humans are becoming as lifeless as the creatures from which they hide. Determined to live for something greater than survival, R, Julie, and their motley crew of companions battle to regain what they have lost, setting both the zombies and humans on a collision path that will reshape the apocalypse.

Amidst the bombardment of inane zombie revivals, Marion’s novel dares to resurrect old lore, and through it, ask the hard questions about what truly makes us human. Finding the answer in the most unusual of places—love between enemies, the lyrics of the Beatles and Frank Sinatra, and the courage to break away from social conventions—Warm Bodies is a deeply touching, frightening, and humorous tale of the end of the world and the beginning of discovering why it’s worth saving.

Marion on Warm Bodies:

Most writers draw on their own life experiences, and Isaac Marion is no exception. When I asked him if he identified with his protagonist, R, Marion stated that—although he was no zombie—he felt like a combination of R and his alter ego, Perry—the young boy who’s memories live on inside him—and that the zombie’s slow transformation mirrored a similar change in his life. Alluding to that post-teen phase where people tend to lose their passion, Marion began writing Warm Bodies when he was trying to revive his own enthusiasm for life. In this way, the themes transform from nihilistic and apathetic influences in the beginning to the exact opposite by the end: “what it means to be alive and what it means of be human.”

While the characters in Marion’s novel answer these challenging questions in a variety of ways, one of the most interesting involves both R and Julie’s obsession with music. Curious about how this theme so thoroughly proliferates through Warm Bodies, I asked Marion why he chose this art form—in contrast to literature, paintings, or film. He explained that music has always been incredibly influential in his life and that for many years he played in a band and made various solo efforts. Furthermore, because “young people are notorious for their love of music,” Marion felt that this fixation was authentic for his characters. When question about his specific choice in iconic musicians—like the Beatles and Frank Sinatra—Marion said that “it just seemed to make sense that in a world without culture that they would latch onto this older generation of music. A nostalgic afterthought when the world was still fun and had culture. It’s their only way to connect with the old world.”

Balancing these monumental themes with the gruesome end to humanity was difficult for Marion, especially given how light and humorous the text remains. “It was tricky,” he explained, “I didn’t know how it was going to play out. I went from scene to scene, working my way through it, editing as I went along, adding some different elements to balance the tone.” Even when the content shifts between absurd, deeply intellectual, and absolutely hilarious, Marion finds the transitions satisfying, stating that they produce “a relief from this deep emotional place, creating a new level of humor when it comes out of something really intense.”

The experience of reading Warm Bodies follows the same pattern. The reader goes in unprepared for the philosophical and emotional depth, and when we suddenly shift from common conceptions of the zombie story to this new realm, we are completely unguarded and shocked by the content. When I pointed this out in my own reading experience, Marion said how universal that reception was, stating that countless people have told him they thought “it was going to suck” and then were surprised when it didn’t. Instead of being angry, Marion says that he understands: “If someone described this book to me, I probably wouldn’t read it. Unfortunately, the marketing of things like this has to go one way or another, so it’s been my responsibility and [the responsibility of] people who like the book to explain how good it is. I’m always on this crusade to convince them to read a couple pages because it’s not what they think.”

Marion did not originally intend on creating Warm Bodies when the idea of his protagonist, R, first came into his mind. Instead, he wrote the short story, “I am a Zombie Filled with Love,” which he published on his blog. While very different from his novel today, this Marion on Writing and Publishing: story received a flood of positive feedback, and Marion decided to expand it into a novel. However, before he even submitted the manuscript to publishing houses, his freelance editor began showing it to people in the film industry and Marion was asked if he’d be interested in selling the movie rights. It was only after Warm Bodies entered the film industry that a literary agent expressed interest in the novel and pushed it to major commercial publication. While this is certainly one of the most unconventional publishing processes we have heard of here at TBL, Marion simply smiled and shrugged at my disbelief. I had not yet realized that Marion had an unconventional writing career long before Warm Bodies hit the shelves.

Although Marion wrote his first novel when he was still a teenager and created another in his early twenties, his primary focus became short fiction. Marion explained that he began by creating HTML interactive stories before he transitioned into more traditional short stories. However, instead of pushing these for commercial publication, he immediately published them on his blog, enjoying the instant gratification of his small internet following. “Without that,” he confessed, “it would be pretty discouraging to write anything because I’d know that I can maybe try to get some dedicated friends to read it. Even if, best case scenario, a publisher snatches it up, it wouldn’t be seen by anyone for a year or so and by then I might be done and tired of it.”

Although Marion’s publishing history is somewhat irregular, his creative process is one shared by most writers. Marion states that he likes to go early to coffee shops and start writing before he has “distractions or interactions with the real world” and he can just dive in when he’s “still semiconscious.” Ideally, he likes to turn off his phone, completely immerse himself in his fictional worlds, and write until two or three in the afternoon before he re-enters society and “tries to have some friends.” But since the overwhelming success of Warm Bodies, Marion confesses that this has become more difficult, stating that he’s “surprisingly busy for someone who doesn’t have a day job or any other particular anchors.” In addition, he finds it difficult to explain to those eager to spend time with him—friends, family, and love interests alike—that, even though he doesn’t have a conventional day job, he has to be strict with his writing schedule. “I feel kind of pretentious when I call it work,” he explained, “because they all know that I’m just going to a coffee shop to stare at a computer for six hours and they’re thinking, ‘Yeah. Work.’ But it demands a certain amount of understanding and respect and needs consistency to be effective.”

Aside from learning to tell your friends “no” when they want to hang out during your “work hours,” Marion also used his own experience to advise our writers here at TBL. Commenting again on how he started publishing his work early on his blog, he pointed out how important and helpful it was to have an instant readership and strong deadlines. While he advises that writers also follow the conventional routes to publishing—cold calling and submitting—“by getting your work out there, there’s always a chance that someone that can help you will stumble upon it.”

Excerpt from Warm Bodies:

I am dead, but it’s not so bad. I’ve learned to live with it. I’m sorry I can’t properly introduce myself, but I don’t have a name anymore. Hardly any of us do. We lose them like car keys, forget them like anniversaries. Mine might have started with an “R,” but that’s all I have now. It’s funny because back when I was alive, I was always forgetting other people’s names. My friend “M” says the irony of being a zombie is that everything if funny, but you can’t smile, because your lips have rotted off.

None of us are particularly attractive, but death has been kinder to me than some. I’m still in the early stages of decay. Just the gray skin, the unpleasant smell, the dark circles under my eyes. I could almost pass for a Living man in need of a vacation. Before I became a zombie I must have been a businessman, a banker or broker or some young temp learning the ropes, because I’m wearing fairly nice clothes. Black slacks, gray shirt, red tie. M makes fun of me sometimes. He points at my tie and tries to laugh, a choked, gurgling rumble deep in his gut. His clothes are holey jeans and a plain white T-shirt. The shirt is looking pretty macabre by now. He should have picked a darker color.

We like to joke and speculate about our clothes, since these final fashion choice are the only indication of who we were before we became no one. Some are less obvious than mine: shorts and a sweater, skirt and blouse. So we make random guesses.

You were a waitress. You were a student. Ring any bells?

It never does.

No one I know has any specific memories. Just a vague, vestigial knowledge of a world long gone. Faint impressions of past lives that linger like phantom limbs. We recognize civilization—buildings, cars, a general overview—but we have no personal role in it. No history. We are just here. We do what we do, time passes, and no one asks questions. But like I said, it’s not so bad. We may appear mindless, but we aren’t. The rusty cogs of cogency still spin, just geared down and down till the outer motion is barely visible. We grunt and groan, we shrug and nod, and sometimes a few words slip out. It’s not that different from before.

But it does make me sad that we’ve forgotten our names. Out of everything, this seems to me the most tragic. I miss my own and I mourn for everyone else’s, because I’d like to love them, but I don’t know who they are.