Quixotic Philosophy: An Interview with Antoine Wilson

Words By Dani Hedlund

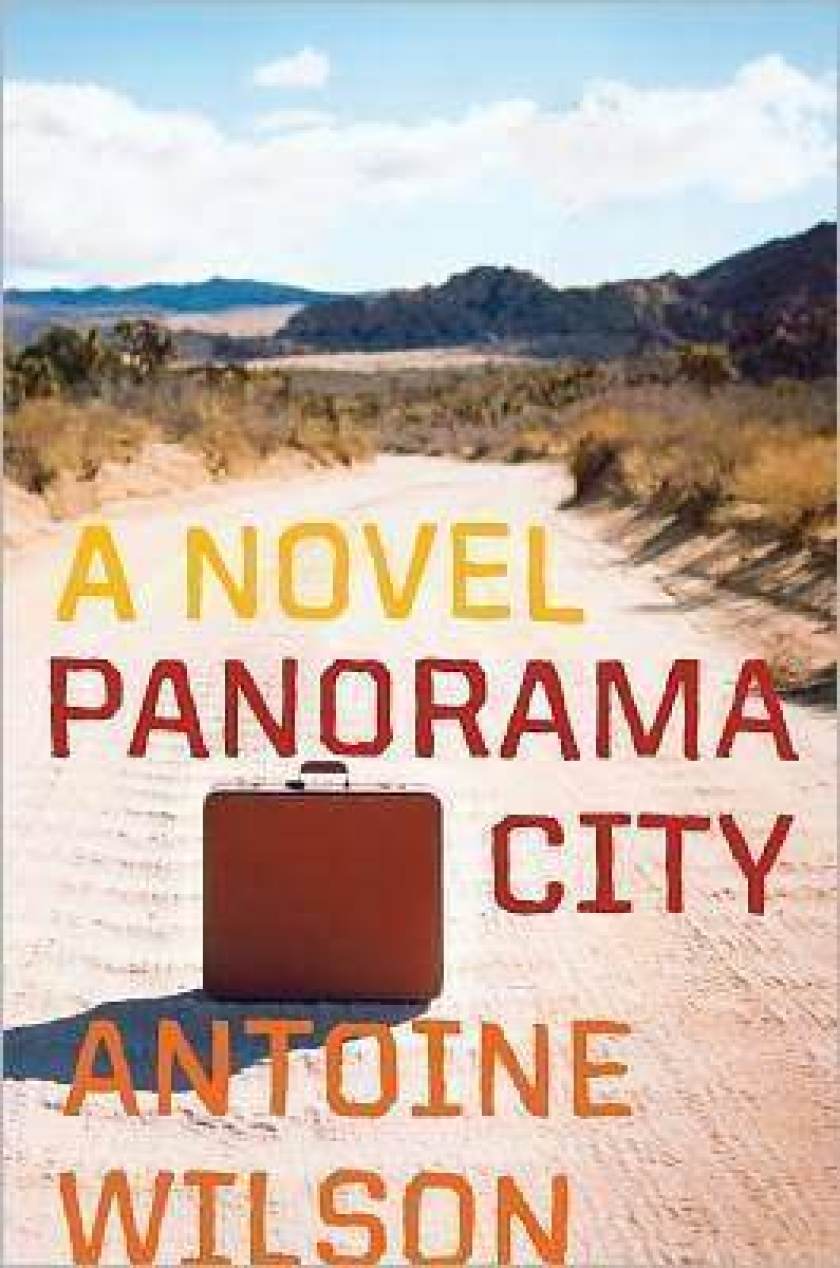

Oppen Porter, the protagonist of Antoine Wilson’s Panorama City, is dying. Currently, he’s covered neck to toe in a white plaster cast, strung up in the hospital, waiting to take his last breath. But instead of enjoying his last few days with friends or his pregnant wife, Oppen is talking into a recorder, rushing to tell his unborn son the story of his life, his philosophy, and the strange events that led to him to Panorama City.

As he tells his son, Oppen’s story begins in Madera, where he enjoys a humble life, one well suited to a self-proclaimed “slow absorber.” However, when he comes home to find his father dead, Oppen makes a mistake that shatters this simple life. Instead of calling the police, he sets to work honoring his father’s wishes, burying him in the yard beside his late hunting dogs, Ajax and Atlas. This act, which sparked a great deal of controversy and government involvement, also gave Oppen’s aunt the ammunition she needed to declare him unfit to take care of himself. Convinced that his father let him “comport himself like the village idiot,” she insists that he move in with her and begin a life as a responsible member of society.

Thus begins Oppen’s quixotic quest to become “a man of the world.” Confronted at every turn by someone else’s philosophy—Paul Renfro’s search for original questions, the Christian Fellowship’s scripture, his fast-food employer’s “happy customers” policy—he navigates an unfamiliar world, often with laugh-out-loud results. As everyone tries to thrust their convictions onto Oppen, he proves that he is not nearly as impressionable as his plain speech leads them to believe. Balancing hilarious satire with the honest, insightful philosophy, Oppen shows us the world through fresh eyes, discovering both truth and ridicule through his gaze.

Just like Wilson’s protagonist, the language of Panorama City is simple yet pithy. Eschewing almost every grammatical marker save the comma, Wilson creates a story that is told rather than written, Oppen’s thoughts pouring into one another in an addictive flood of narration. Since the entire novel is “recorded” on cassette, we are also privy to wonderful verbatim conversations with those at the hospital, his sleepy wife occasionally popping in to make corrections or additions to the tale. These instances create a perfect anchor to the present, never allowing us to forget the fatal conclusion awaiting our narrator at the end of the recording.

It is with great excitement that Tethered by Letter’s recommends this unique novel. Simultaneously philosophical, satiric, and literary, Panorama City revamps the quixotic quest, creating a story that stands out as starkly as its six-and-a-half-foot narrator. Just like Oppen, Panorama City may struggle to find a place where it belongs—after all, it is quite different—but in the end, whoever settles down with it, will find a new love and an astute worldview within its pages.

Wilson on Panorama City

Changing gears from the dark themes of his first novel, The Interloper, Wilson wanted to try something new with Panorama City. Inspired by Don Quixote, he fell in love with the idea of “the big sprawling comic novel,” and decided to combine this idea with his desire to write a story that reflected his philosophical outlook. “I wanted to write a big, new, contemporary road comedy,” he explained, “which was not was Panorama City turned into, but that was always the emphasis.”

Just as Don Quixote meets new adventures on his travels, Wilson planned for Oppen, his main character, to encounter new characters on his quest to “become a man of the world.” Each of these individuals has a very defined philosophical outlook, which is where much of the satire comes to life in the book. Wilson explained that, “early on, part of what interested me, as a basis for a comic novel, was this idea of competing ideologies and people who define themselves by those philosophies and try to impose those ideas on others.” Thus, instead of encountering new lands, as Don Quixote did, Oppen is confronted by new outlooks, having to battle against their control with his mind rather than his sword.

With the comedic quest fixed in his mind, Wilson needed to construct his hero. When I asked what inspired Oppen’s unique character, Wilson explained that before he started the book—“when I had the ideas bouncing around in my head”—he essentially met the real-life Oppen: “He was very tall and he said that he had a lot of friends in a lot of different places and he asked if I wanted to be his friend. He had this really open, naive, friendly character. He was really there, physically walking down the street, and he was really the inspiration for Oppen.”

Although the inspiration for the theme and characters came easily to Wilson, he struggled initially with the voice. In early drafts, he toyed with different narrators, turning to a third-person storyteller since Oppen himself can’t read or write. “But then there was a point,” he explained, “where I realized that I wanted Oppen to tell his own story, and I wanted him to be telling it verbally…there was just something exciting to me as a writer to try to write something that’s spoken.” After making that crucial choice, he decided that having Oppen record his story on cassette tapes made the most sense. Yet, since this was a relatively experimental form, it took Wilson several drafts to balance all of the possibilities. For example, when he first started out, he said that he included a lot of background noises from the hospital in brackets: “it just got really distracting and they looked more modern than they were…little dazzlies dazzilies that needed to go away.” However, these “dazzlies” did give him the idea to record Oppen’s conversations directly with his wife, which make for some of the most interesting narrative passages in the novel.

Wilson on Writing

Over the four-year period Wilson wrote Panorama City, the novel changed immensely. “Early on,” he explained, “there was this huge road novel section where Oppen and Paul Renfro got into Renfro’s crazy car and they drove through Vegas, planning on going to the Institute for advanced study in Princeton.” He was full fifty pages in before he realized that it wasn’t working. “I tried to take the show on the road,” he summarized, “but it didn’t work out.”

This type of significant rewriting is not uncommon for Wilson. Speaking of his writing in general, he explained that “in the first drafts, after I have all my ducks in a row, I get to about one-hundred pages, and then I realize ‘oh, this is all coming apart,’ and then I do another draft, and I get to about 130 pages—or some reason, 130 is a big hunk for me—and then that one falls apart too…but then the third time, I had everything lined up…which is a really painful process to go through, but I think it yields something with texture.” In fact, Wilson spoke out against writing ‘just to get to the end’—without making sure the novel is working—even though he understands the urge: “It’s painful to create something out of nothing everyday so sometime it seems like a good thing to just get to the end. You think that if you do, you’ll finally have something…but usually it turns out that that thing is just going to end up being a deleted file.”

Panorama City was no exception to this rule. In fact, after working on it for two and a half years, Wilson end up “throwing away everything and just starting over.” He took a whole month off from the project all together, and then started again from scratch. “But you know,” he added, “it was those two years of accumulated knowledge and writing that allowed me to move through and write the manuscript in another few years.”

Excerpt from Panorama City

If you set aside love and friendship and the bonds of family, luck, religion, and spirituality, the desire to better mankind, and music and art, and hunting and fishing and farming, self-importance, and public and private transportation from buses to bicycles, if you set all that aside money is what makes the world go around. Or so it is said. If I wasn’t dying prematurely, if I wasn’t dying right now, if I was going to live to ripeness or rottenness instead of meeting terminus bolted together and wrapped in plaster in the Madera Community Hospital, if I had all the time in the world, as they say, I would talk to you first of all about the joys of cycling or the life of the mind, but seeing as I could die any moment, just yesterday Dr. Singh himself said that I was lucky to be alive, I was unconscious and so didn’t hear it myself, Carmen told me, I’ll get down to so-called brass tacks.

First of all, ignore common advice such as a fool and his money are soon parted. Parting with money is half the pleasure, and earning it is the other half, there is no pleasure in holding on to it, that only stiffens the vitality, especially in large amounts, though the world will advise you otherwise, being full of people who would make plaster statues of us. Second, I haven’t made knowledge of life yet, I’m only twenty-eight-years old, when you get to be my age you’ll know how young that is, and if you’re a man of the world by then I salute you, the road isn’t wide or straight. Everything you need to know is contained in my experience somewhere, that’s my philosophy, but I’m afraid you’re going to have to make the knowledge out of it yourself. The world operates according to a mysterious logic, Juan-George, I want to illustrate some of its intricacies, so that you can stand on the shoulders of giants, not, as Paul Renfro used to say, the shoulders of ants.

For the first twenty-seven years of my life nothing happened to me. I rode my bicycle into town every day from our patch or wilderness, I rode into Madera and asked my friends if they had any work of me, everyone called me Mayor, even Tony Adinolfi, who was the real mayor, called me Mayor. Then came my so-called mistake…