Plastic Man Turns 80: Paying my respects to Jack Cole a second time

Words By Dominic Loise

The hotel my older brother was working at in Rosemont, Illinois was having a comic book convention. It was back in the 1980s so about a decade off from the convention center comic cons here in Chicagoland. It was my first ever convention. I had a local comic shop where I would spend my weekend lawn-mowing allowance on current issues, but this hotel basement opened up a new world to me. My brother paid my entry fee but told me to make my money last because I had to hang out his entire shift. My wallet was empty by the time I hit the first comic book dealer’s table.

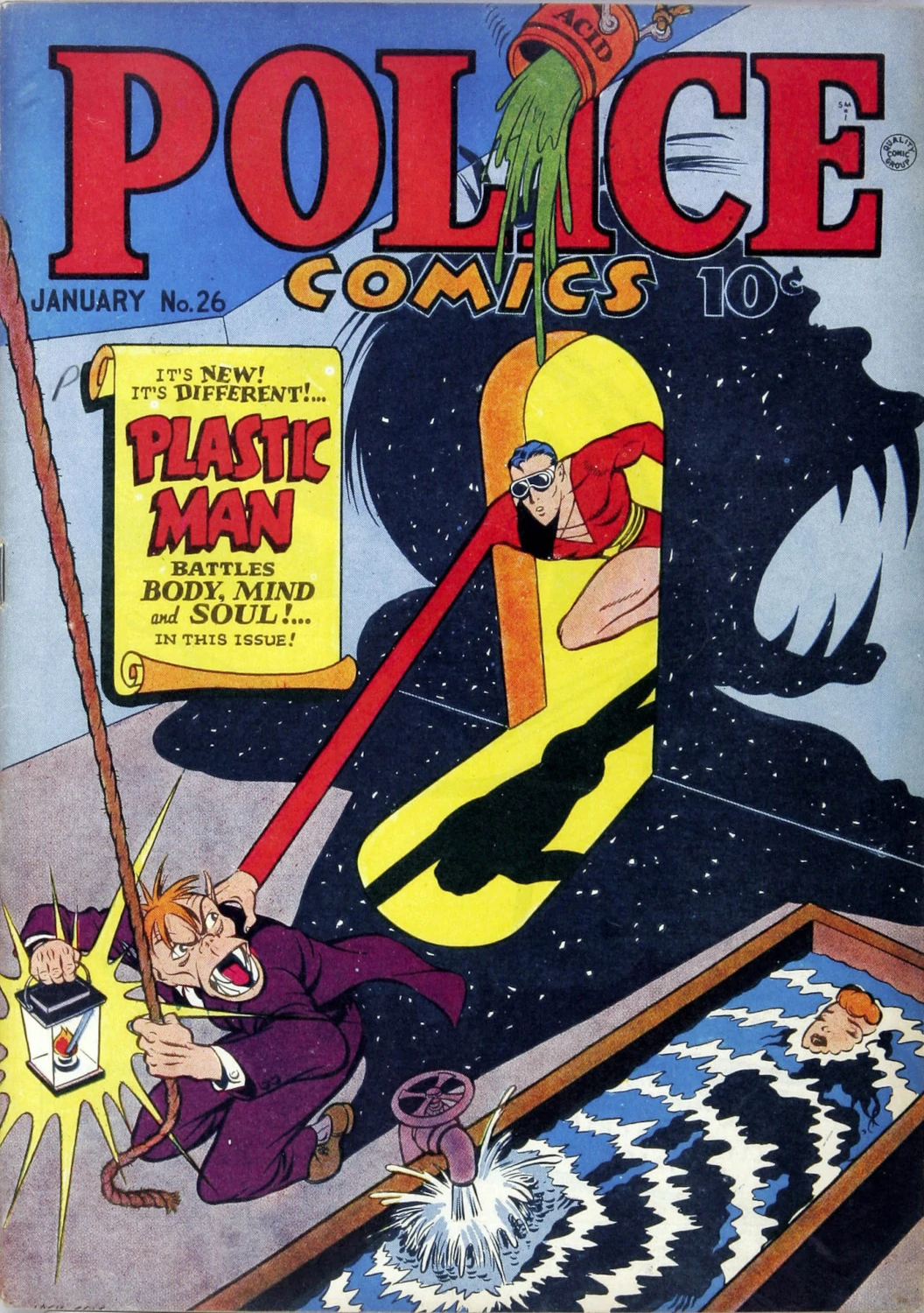

Up close, I had seen Silver Age comics from the 1960s and Bronze Age comics from the 1970s, but I had never before seen Golden Age comics from the 1940s, which saw the introduction of comic books to the marketplace. Craning my neck to see the wall of comics behind the dealer, I looked up at a beat-up copy of Quality Comics’ Plastic Man #26. Maybe it was the primary color scheme of the cover or that the page dimensions were larger, the draw of “52 Big Full Width Pages” next to the price tag of ten cents. Maybe it was the familiarity since I grew up watching The Plastic Man Comedy/Adventure Show. But mainly, I think it was because of the cover art by Plastic Man creator Jack Cole, showing Plastic Man fully stretched, his face stoic and calm, not the wacky, Jim Carrey-esque caricature we sometimes see in the DC Comics issues and animated versions of Plastic Man. In this essay, I want to go back to the beginning and look at a man named Patrick “Eel” O’Brian, a former gang member transformed into an iconic superhero. For the eightieth anniversary of Plastic Man, I would like to take a look at the first appearance of the character and the ways my mental health awareness aligns with Patrick “Eel” O’Brian becoming Plastic Man.

On the first page of Police Comics #1 (August 1941), we open on a robbery underway at Crawford Chemical Works. Just as Eel cracks the office safe, the chemical plant’s security guard bursts in on the gang. Eel, the last one out of the office, takes a shot from the security guard’s pistol, throwing him off balance. An unstable Eel tips a vat of acid over himself and into his open gunshot wound. He is still able to escape capture but misses out on the gang’s getaway car, who all wave “adios” as they drive off without him.

My first mental health takeaway (which is a term I will use going forward to connect Plastic Man’s character arc and my work on myself in therapy) is to know who my true friends are. When I got to the point where I had to check myself into inpatient care for self-harm, I filled out paperwork asking me who I would turn to if I got to this point again. Unfortunately, the friends I put down on the admission paper weren’t there for me going forward. I remember asking my family on visitor’s day if they contacted them as I looked to the doorway, waiting. And when I got out of the hospital, they weren’t willing to be part of my healing process. They were the people I wanted to be there for me—I admired them, wanted to impress them—but not the people I needed for healing, those who I didn’t have to don a persona for in order to receive support.

Abandoned by his gang, Eel escapes through swamps and up a mountainside till he passes out. He wakes to find himself in Rest-Haven, a retreat of monks. The monks who discovered Eel give him a bed to recuperate in. They also give him a second chance by turning the police away, who are on a manhunt for Eel and his gang. When Eel asks why he wasn’t turned in, a monk explains that Eel needed a chance to not be burdened by his past, and the monk listens as Eel tells the story of what hard knocks led him on his path of crime. How he grew up an orphan being beaten down by everyone, learning that the only way to make it in the world was to take what you wanted. It is in Rest-Haven that Eel reshapes himself and discovers his stretching powers to become Plastic Man. Eel learns that he does not have to always push back at the world because sometimes there is a helping hand instead of another slap down. Unburdened by his past, Eel literally stretches to relax after talking to the monk and notices his arms extending.

The next takeaway is to find my Rest-Haven; self-care is important. I have learned the benefits of talk therapy to help me be in the moment mentally and not lose myself to racing thoughts of “what if” scenarios or be haunted by past trauma. Being in my head with these thoughts, I do not focus on the conversations around me, which leads me to miss out on my life and its enjoyable moments. Those that know me can even recognize my tell when I am too much in my head, how my lower jaw juts out and I look like a caged gorilla at the zoo (I’m a very large man for those who have not met me). I may not have the elastic powers of Plastic Man, but through talk therapy, I have slowly been stretching myself over the years into being present. It was trial and error in the beginning to find a therapist who was a right fit but once I found that person, I was able to reshape my perspective of the past and be present. Sometimes I am totally drained after these sessions. It is like being wiped out after a gym workout. So, I give myself the time needed after sessions to recuperate. I always make sure that therapy days are on my days off and give myself the remainder of the day afterward for a walk wherever the sidewalk takes me, taking in the world around me and seeing what I can capture on my phone’s camera. There are also the options of writing (I am a big fan of art therapy), reading, or TV. If I need a nap after therapy, I view it as necessary restorative sleep and not depression sleep. Even Plastic Man needs to pull himself back together.

The remainder of the issue sees Eel “rejoining” the gang for a heist only to one-up them as Plastic Man and turn them into the police. Eel demands to drive the getaway car on the next caper. When the gang enters the building, he shifts his face and body into Plastic Man. As Plastic Man, he stretches up multiple floors to get ahead of the gang, such as morphing into a rug at the bottom of a flight of stairs to catch them up, frazzling them, and making them think that Plastic Man is everywhere in the building almost at once. When the gang returns, he jumps back into the getaway car, changes back into Eel, and drives them straight by the police station. Then, the new “long arm of the law” sneakily grabs the gang members from outside the driver’s window, pulling them around the car to drop the crooks off at the station. Eel is ironically believed to be the only one to get away this time, allowing him to have a secret identity that infiltrates criminal gangs only to bust them up as Plastic Man.

My final takeaway is to ground myself in the room I am currently located. Through grounding—a practice where I work on being present in a situation when I feel overwhelmed or manic—I’ve learned how to be present in each room, to not anticipate my next move or be triggered by past trauma. By focusing on my breathing and feeling my feet on the floor, I can prevent myself from being uprooted and remain in the moment without pulling myself away with anxious thoughts or soaking in the toxic energy of others. For myself, I find I don’t have the power to bend the universe to my will, nor do I wish to, and my reacting manic to a situation is a sign that I don’t wish to deal with reality, but grounding allows me to be present in a moment and focus on the situation at hand with a clear head. I need my focus to be with me and where I am currently at in the present moment.

Plastic Man catches a lot of crooks by taking in his surroundings, morphing into objects, and waiting things out. Plastic Man is sometimes posing as inanimate objects and needs to not be an anamorphic object if he is going to come across as what he is turning into. (Meaning, a walking, talking briefcase wouldn’t fool anyone in a ransom money drop-off.) As Eel, he has to stay in his own lane to keep up the appearance of a criminal to remain undercover. The magic of Jack Cole’s Plastic Man is that it’s a kooky world, but Plastic Man adapts and morphs to meet each outlandish situation. Plastic Man gets misconceived as a walking cartoon character instead of the dual identity of Eel O’Brian/Plastic Man, a former criminal identity who changes into a heroic persona as a means of adapting to the world around him. The malleability of Plastic Man allows him to be more of a reed than the mighty oak he was before the accident and his time at Rest-Haven, someone who wasn’t going to budge for anyone. Now, Eel can go with the flow and adapt to the situation instead of being a tough guy bending the situation to his whim, or breaking under the pressure.

Another way I stay present is by observing pareidolia around me when I am out walking instead of being caught up in my head. Pareidolia is noticing shapes or faces in inanimate objects, like cracks in rocks that look like a smiling face or crumples in a discarded napkin that look like a dog. It’s like when you look at the clouds to see shapes, but without trying to Rorschach Test an image and instead stumbling on the moment naturally in the wild. Crooks in the comics don’t notice Plastic Man taking the form of an inanimate object because they are not focusing on their surroundings, only their actions. So, in these early issues, Plastic Man is not a human cartoon disconnected from the real world: he connects to the world in the comics by blending into his surroundings to wait out criminals; he processes but does not absorb shots or punches from others, they bounce off him; and most of all, he knows when to be Eel and when to be Plastic Man.

The tragedy behind Plastic Man is that Jack Cole died by suicide on August 13, 1958, in Crystal Lake, Illinois. At the time, he was working as an illustrator for Hugh Hefner at Playboy. Cole’s suicide note to Hefner can be found in the book Jack Cole and Plastic Man: Forms Stretch to Their Limits! by Art Spiegelman and Chip Kidd (Chronicle Books, 2001). I remember being hit hard by that read to the point where I drove almost an hour to Crystal Lake. After the biography’s publication, Jack Cole was being discussed and how his death by suicide left so many questions. But I wasn’t at the lake looking for answers. For me, though I wasn’t able to verbalize it at the time, I needed to be in the space not just because I was a fan of Jack Cole, but because I didn’t feel there was anywhere I could go to talk about my own thoughts of suicide.

Jack Cole was not being selfish to take his life by suicide—he was dealing with mental health issues, and society in the 1950s was not in a place where men could talk openly about those things. I took the afternoon to apologize to Jack Cole that mental health awareness wasn’t better during his time. I walked back to my car repeating to myself that I wanted to live. On the drive home, I thought about that same persistent stigma waiting for me as I looked for help for myself—I had a doctor who told me there was “nothing wrong with a nap” when I said I was too exhausted to do anything. My family and my employer facilitated my need to mask my struggles with a plastic grin out of a fear of breathing in their toxic positivity and gaslighting when what I really needed was their unbiased support. My own path of mental health wasn’t instantaneous. I did not just snap back like a rubber band after that trip to Crystal Lake. It was facing the stigma of getting help as I was growing up, it was that emotional drive home from Crystal Lake, it was having one day years later where I thought I couldn’t handle things anymore, it was finally asking for help that same day, and it is now diligent daily upkeep on my mental health. And it is worth it.

Jack Cole created some visually stunning advisories for Plastic Man, like the giant who walked on his hands (Police Comics #11) or when we first met future sidekick Woozy Winks (Plastic Man #13) whose supernatural good luck causes an unreal infallibility to his crimes. I found the trick to Plastic Man was that he wasn’t the zaniest one in the room but adapted to the oddest things Cole could think up. In the end, Plastic Man would pull himself together returning to form. Deep down, having that Plastic Man comic under his arm helped that grade school version of me as he left the basement convention. He kept at it, reading and supporting the non-mainstream superheroes. The next decade, that kid would be older and go to the comic convention at a large event center down the road. Decades later, he would see that convention move downtown, everyone cosplaying as their favorite characters and people on the street wearing superhero T-shirts from blockbuster movies. The world has become that hotel basement. That kid in the hotel basement picked up a few things from Plastic Man, adapted to our own off-kilter world, and lived to see fan conventions take the hint as well, expanding to not just talk comics, but to address mental health awareness and the necessity of suicide prevention with booths for suicide awareness organizations on the convention floor and panels for mental health on their schedules. Seeing comic conventions as a place I sought to escape from my problems now becoming a community to end the stigma around mental health, I couldn’t think of a better eightieth birthday present for Jack Cole’s Plastic Man.

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 800-273-8255

Trans Lifeline: 877-565-8860

The Trevor Project Lifeline: 866-488-7386

Find your closest crisis center: suicidepreventionlifeline.org/our-crisis-centers

Psychology Today Therapist Finder: psychologytoday.com/us/therapists