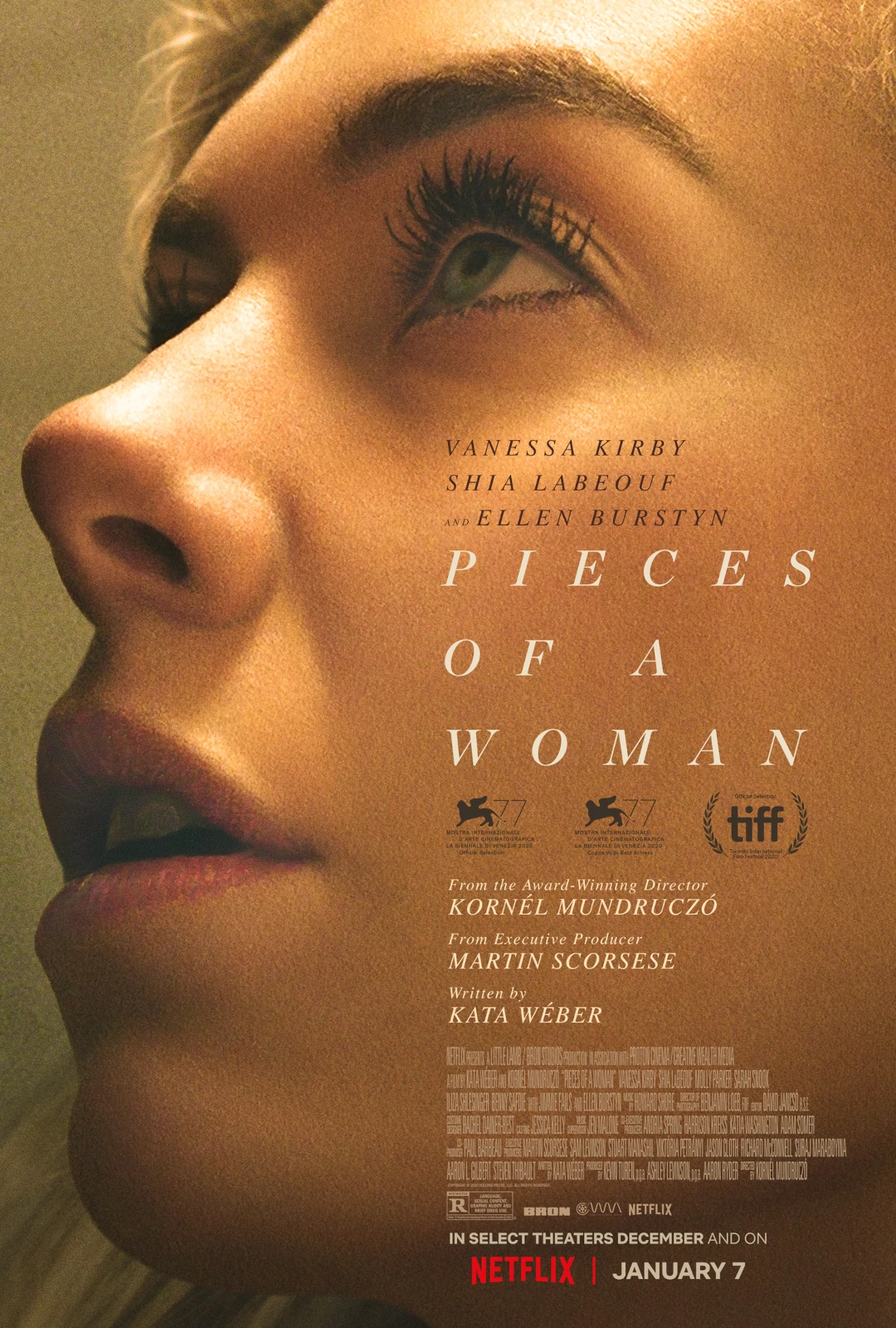

Piecing Women Together: The messy grieving process in Pieces of a Woman

Words By Maria Swiatkowska

When a woman I love lost her boys to miscarriage she planted pine trees in her garden and waited for them to grow. When Vanessa Kirby’s character in the film Pieces of a Woman, Martha Weiss, lost her girl right after she was born she put apple seeds between moist cotton pads in her fridge and waited for them to sprout. The former is not my story to tell, on the latter, however, I can elaborate freely. All of us, whether imaginary or flesh and blood, have our own weird, winding ways we embark on to process our grief. These pathways are difficult to trace back or explain, but the urgency of putting them out there remains potent. Art conveys the stories we want to be told but can’t quite get around to telling. Ones that are filled with awkward silences and uncomfortable questions.

Like, how do you mourn for something that never got the chance to truly be?

In grappling with that question Pieces of a Woman emerges as a fine piece of storytelling art, even if the story it tells seems filled with peculiar rituals the meaning of which we don’t fully understand. But it doesn’t seem wrong or out of place: after all, the grieving process is often murky, opaque to those around the bereft. At first glance, Martha may come off as difficult to those who try to provide her with an emotional support network. She refuses the comfort of intimacy to her visibly suffering partner, leaving him to balance on the brink of relapse and turning the blind eye when lapse he does. She fobs off her concerned sister, acts defensive towards her increasingly demented mother, and kisses a (token black) colleague at an office party. Her grief is not a neat linear process and for most of the film she’s not even visibly processing anything. And this excruciating, tedious quality is, I would argue, the best thing in the whole film. Too often we get stories that are clear-cut and task-oriented: the bad thing happens, you process it, with perhaps just one minor setback occurring around three-quarters of the movie, and—bang!—you’re good to move on with your highly functioning life.

Meanwhile, the strenuous work of grieving is not the stuff of action movies. Those who try to come to the rescue often end up doing more harm than good, adding to the griever’s pain their own frustration about the inefficacy of help they—as rescuers—are trying to provide and failing to realize that there is no quick or easy fix. Such is the case here. To Martha’s family circle, what is perhaps the most frustrating part of her messiness is her refusal to blame the stand-in midwife; the woman who helped deliver the baby and for a split second partook in the joy of her flash-like motherhood. It is especially Martha’s mother who tries to push her own agenda, fixated on the idea of getting some kind of revenge for the death of her grandchild. This brings me to the two directions that I think the story could have developed more, which might have made it an even more compelling film to watch. The first is how the generational trauma of the Holocaust is brought up by Martha’s mother as leverage and how Martha is clearly reluctant, if not altogether unwilling, to partake in her difficult heritage as a Jewish woman. The second is how the prosecution of a midwife by an affluent family plays into the social-class conflict. Mentions of the former are scattered throughout the movie but never explored in a thorough way that a sub-plot of this gravity deserves. Of the latter there is but one indication, in a scene when Martha overhears news coverage of the trial while sitting in a cab but refuses to listen, turning her head away to stare blankly out of the window.

As she detaches from what the TV reporters are saying, the viewers can feel locked out of this other story. All throughout the movie we can sense another tragedy unravelling, not before our eyes but beneath the surface—the life of Eva, the midwife, being implicitly, systematically dismantled by the investigation and the court proceedings. This could also be a potential source of frustration for some viewers; in particular, the awareness that all the while somewhere out there another story is taking place. One that could provide more dramatic, tear-jerking—and maybe even cathartic—moments. What could be this juicy courtroom drama turns into a long-winded, psychological journey, or perhaps a trip, given that the main characters seem intoxicated by their mourning, tightly cocooned in soundproof grief. But even though some sort of overt conflict or confrontation between Martha and Eva could have given the movie more dramatic impact, the movie takes a different approach—a more empowering and less obvious one. Through the entire film, Martha’s family circle puts increasing pressure on her to punish Eva, pitting the mother against the midwife to orchestrate a battle that the bereaved woman wants no part of. A battle in which her personal tragedy becomes compartmentalized, supposed to serve as a pretext—which is what, ultimately and bravely, she refuses to do.

There is another movie that echoed in my mind while I was watching Pieces of a Woman, particularly the scene that took place in the courtroom where Martha finds her own voice and refused to cast the blame on Eva. The exchange between Eva and Martha—admittedly nonverbal, but intense nevertheless—reminded me of a scene in Love & Other Impossible Pursuits, where still-bitter wife #1 (Lisa Kudrow) confronts much-maligned wife #2 (Natalie Portman) tormented by the cot death of her newborn daughter. Rather than using this moment of vulnerability to her advantage, Kudrow looks at the other woman and pointedly tells her, “You did not kill your baby.” There is something quietly moving and powerful when characters refuse to play by the rules of the world that incentivizes them to hate each other and teaches them that the downfall of one will be the triumph of the other.

The whole shtick of pitting women against each other is older than cinema itself. Our pop culture, much like our history and our media, is rife with examples of putting women on trial to shine on them the spotlight of shame. A cold, blinding light that they either internalize or choose to avert to other women. The often source of conflict is the man, because of course it is. The infamous Bechdel test has demonstrated time and again that in most screenwriters’ minds no thing is of more concern to women than male attention. But when the core of potential conflict is not a male, but the particularly female experience of motherhood, that is where things become interesting. The ultimate manifest solidarity between two women positioned by circumstance to be rivals is a much-needed relief to the viewer. Especially since, at this point, we have witnessed a fair share of blame-tossing aimed both at the invisible midwife and the bereaved mother, who for the most part refuses to pull herself together and play according to the fixed rules of orderly grieving (whatever those might be).

Given the poignant beginning and the interesting (though at times underwhelming) development of the movie, its end might ring a bit off-key. After the pivotal (if a bit melodramatic) courtroom speech comes a teatime reunion with Martha’s mother and sister. It’s a final bright-green shot of hopeful days that could lie ahead once the apple seeds sprout and grow into tall trees. Seems a bit corny, like a technicolor-tinted cliché found in feel-good movies, which this one manifestly is not. But there is a deeper truth to all this, which is that, in order to heal, women should not let themselves be systemically antagonized and pitted against each other to provide an easy fix for what they know is unfixable. Martha’s child does not resurrect, her mother’s dementia does not retract. Life is still pretty tough as it is. But there is hope in forging those bonds and refusing to give in to revenge. Ultimately, the film shows us Martha’s reward for that refusal is the opportunity to piece together her womanhood by returning to the vital relationships with the women in her life. And maybe, in the years ahead, the possibility of creating a new life, a new beginning, a new woman. The final credits left me wondering whether that was cheesy, but it felt true, nevertheless. And if sometimes the truth comes with a whiff of cheese, so be it.