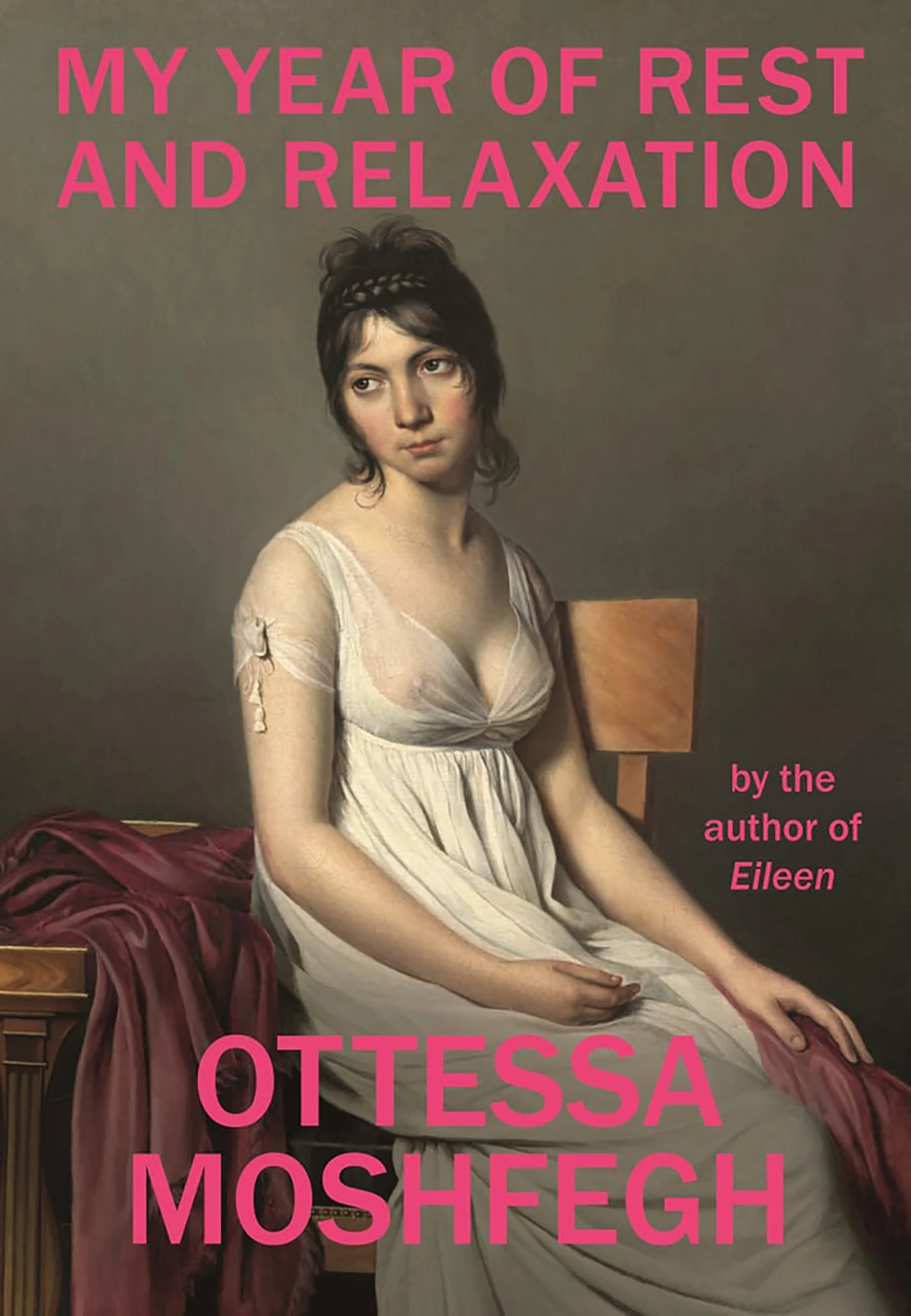

On My Year of Rest and Relaxation

Words By Ariel Fagiola

I can honestly say I’ve never read anything like My Year of Rest and Relaxation. There’s no adventure or mystery. No conventional story arc, not a highly satisfying conclusion. What’s there is a masterfully written pseudo-memoir of a woman who decides to sleep for a year.

Ottessa Moshfegh’s protagonist is not a hero—she is not even very likable. Her self-destructive and neurotic behaviors made me laugh, contemplate, clench my fists, and grind my teeth. Unlike so many distraught female characters who seek reformation, Moshfegh’s narrator never apologizes for her actions. Everything she does is calculated, focused on personal gain rather than emotional need or desire. She knows what she wants from her hiatus from “normal” life and refuses to let anything or anyone get in her way. Moshfegh emphasizes her protagonist’s ill-advised behaviors not by normalizing them, but by presenting them without the possibility for reformation. The intent of the narrator is so strong that the reader has no choice but to follow along her destructive path.

The narrator has opinions and thoughts that can be classified as conventionally shameful, further separating her indulgent behavior from “normal,” more functional members of society. When discussing details of her romantic relationships, instead of swooning or focusing on the qualities of the man, she talks about what she gets sexually or materialistically out of the arrangement. When she must attend a funeral, instead of feeling remorse or sorrow for those affected, she acts selfish and needy, requiring constant attention and naps. I was sucked into her world of shamelessness and absurdity, nearly cheering her on by the end. Her frustrations and honesty were oddly refreshing and forced me to think about the human condition in a light that was highly uncomfortable at times—Moshfegh’s narrator is highly privileged; she has a deep inheritance and a nice apartment; these are all things that allow her to embark on her year of rest. This privilege causes her sharp indifference towards both her surroundings and really anything not directly related to her.

The way the narrator handles friendships and lovers isn’t admirable. She treats those around her like pawns in a plan that only concerns her wellbeing. At the same time, she isn’t concerned for herself; her attitude seems to stem from a lack of real emotional depth or the will to feel connected to others. She wants to rest, forget her surroundings, and in essence forget herself. The few people close to her are absolute enablers. Yet there’s still so much thought forced upon the reader about the complex relationships the narrator chooses to keep. Why does she bother maintaining friendships if she refuses to show a deeper interest? Despite her destructive actions, she’s able to stay attached—though the other characters, like her supposed best friend Reva or on-again-off-again, borderline-sexually-abusive partner, are hardly what I’d call supportive. The narrator does offer reflection on her past, focusing on the sedated relationship she had with her parents, to give the reader context for her ridiculous actions. However, she does not use the reflections to grow in any way. They provide necessary background and severely interesting memories, but that’s it. In contrast, the narrator’s interactions with others add depth to her otherwise very private behaviors, allowing the reader to view her more as a recluse than completely heartless.

The narrator seeks professional help from a psychiatrist throughout the novel, not as a means for improvement but to gain access to a seemingly endless amounts of pills to aid her sleep. Moshfegh does something extremely crafty with her use of prescription drugs. The narrator doesn’t take them simply to get high or to forget it all; she continually states they are to aid her rest, lying constantly to get more and stronger doses, convinced her sleep is still not enough. Her dramatic need for drug-assisted sleep forces the reader to consider the current epidemic of prescription drugs in America, despite the plot taking place prior to the rise of pharmaceutical prices. This extra layer is pertinent for the progression of the narrator, while planting a little seed of query that grows throughout as the reader explores the nuances between reality and fiction.

My Year of Rest and Relaxations allowed me up and pressured me into truly letting this narrative’s quirk and absurdity take control. Moshfegh is a powerhouse, and this latest novel is truly remarkable. It doesn’t depend on charm and refuses to apologize for its absurdity—I cannot stop talking about this book.