Nuclear Fallout, Strange Science, and Demonic Imagery

Words By F(r)iction Staff

Carolyn Janecek

Cherry-syrup blood, homemade flamethrowers, and nuclear fallout. That’s what my favorite franchise, Mad Max, has in common with Netflix’s new original teen drama, Daybreak, where high school cliques form into warring clans when all the adults are killed or mutated by the missiles’ bioagents.

Daybreak’s protagonist is by no means Furiosa (or even a Max Rockatansky). He’s Just Josh––an extra-entitled, straight, white “nice guy” with a skateboard and a katana. I took to calling him “Boring Josh.” When I’m that annoyed with a protagonist, I rarely get past episode two. Daybreak is different though. It’s kitschy and chaotic. Josh speaks directly to the viewer, at first, appearing to be the only “sane” kid left in the world, who isn’t out murdering people for funsies.

But soon enough, even the viewer is questioning reality and most importantly, questioning Josh. The world expands beyond Josh and soon the other protagonists are taking over his narration and presenting this post-apocalyptic setting through their own television tropes––whether it’s a celebrity voiceover or a laugh-track sitcom. Josh sees himself as a knight in shining arming, but the audience gets to see him tarnished.

In comparison, the broken and traumatized minor characters who start out––in Josh’s eyes––as antagonists, have satisfying character arcs. The ten-year-old, genius/pyromaniac Angelica confronts her abandonment issues and finds a her mother figure in a world where all adults are flesh-eating ghoulies. Ex-Jock Wesley Fists seeks his “samurai redemption” and eventually has to face the many personas he’s had to play in his public and private life as a black, gay football player. Even the star quarterback, who is a clear homage to Mad Max: Road Warrior’s Lord Humungus, shows his humanity (just before impaling one of his enemies in a pit of spikes).

In Daybreak, everyone has a story to tell and almost no one is telling the whole truth. The show is tropey, campy, and very extra, but it left me fascinated by the way these high schoolers struggle to create elaborate and flawed ways to cope with loss.

Andrew Jimenez

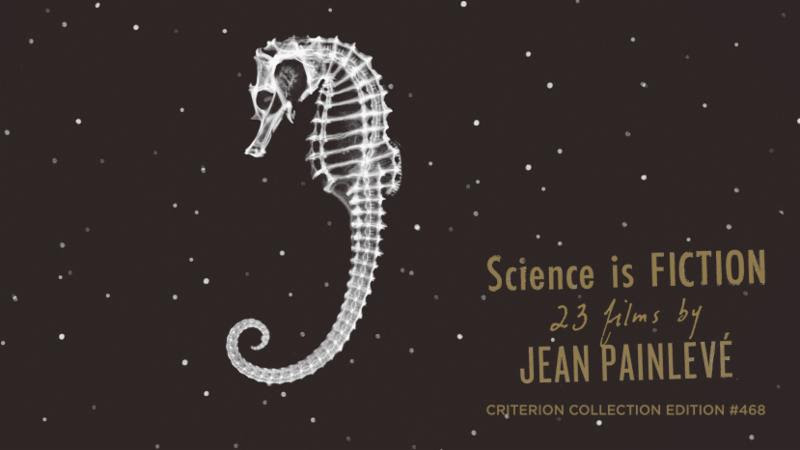

Lately I’ve been mesmerized by Science is Fiction: 23 Films by Jean Painlevé. Covering topics ranging from diatoms to sea urchins to pigeons, these surrealist shorts seem too artful and abstract to be real, but with them Painlevé—a scientist and inventor who combined those two skills into a career as a filmmaker—ensures that they are serious science. The earliest of his films, covering various sea life, were made in the 1920s and 30s, and were technological feats for their time. But the work modern viewers will find most satisfying were made in the 60s and 70s. With an experimental score by Pierre Anglès, Diatoms, in particular, is a delight. Anyone with a Criterion Channel subscription (or who knows someone who does) can view the films now.

Eileen Silverthorn

The spooky season is still going strong in my house! I’ve been watching CBS’s Evil. This show gives you the foreboding creepiness of The Exorcist mixed with the analytical qualities and moral dilemmas characteristic of a crime drama. We follow Kristen, a clinical psychologist, who is hired by the Catholic church to help priest-in-training, David, assess whether miracles and demonic possessions are real, or are just medical anomalies and mental illnesses with a spiritual guise. A true exploration of the overlaps between science and religion, heavily seasoned with chilling demonic imagery (whether you believe or not)!