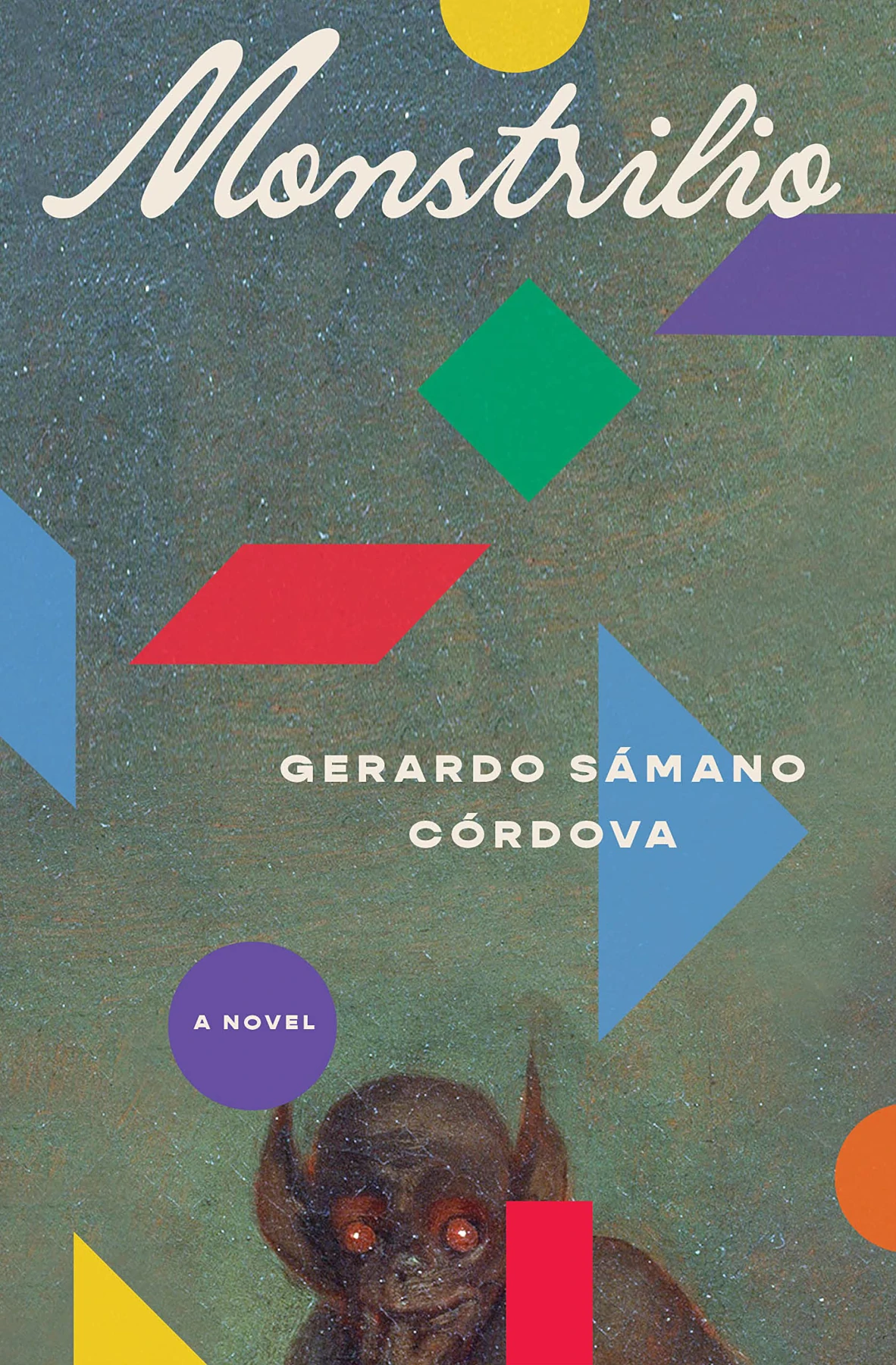

Not Your Average Frankenstein: Exploring Grief, Sexuality, and the Monster in Gerardo Sámano Córdova’s Monstrilio

Words By Corrine Watson

Published by Zando Projects on March 7, 2023.

For readers with a soft spot for unconventional monster fiction, Gerardo Sámano Córdova’s debut novel Monstrilio is packed with metaphor and nuanced layers of horror and humanity. The novel draws the reader into the raw, intimate spaces of mourning and creates something distinctly original as the story effortlessly blends speculative horror with grief, sexuality, and what it means to be human.

The novel follows a grieving family after the death of their son, Santiago, who was born with one lung. In her grief and desperation to hold on to part of her son, Magos cuts out a piece of the lung that both sustained and failed her child. Magos’s inspiration came from a play where the actress lapped up her dead son’s blood as she wept over his body, and as Magos cuts into her own son, “She savors her Santiago’s blood, a taste of iron and warmth. She could suck more blood out of his veins, but she won’t; she’s not a vampire though now she understands the impulse—the craving to drink deep and thirsty in her bowels.” Magos’s choices here are disturbing, but awkwardly justified as Córdova draws the reader into her grief, and this over-the-top, ghoulish action resonates with the raw desperation and tenderness of a mother clinging to her child. As this piece of dead flesh takes life, and morphs into a human-like creature, this desperate thirst and unsatiated hunger follows Monstrilio throughout his life and separates him from humanity.

The reference to folklore and reincarnation, while not particularly subtle, quickly brings the reader up to speed and takes some mysticism out of the equation when the lung takes on a life of its own and transforms into something more in line with a deformed animal than a child. Magos is determined to raise the creature she names Monstrilio in place of Santiago in spite of his violent nature and the pressure from her family to kill it. From Monstrilio’s unusual beginnings, the tension of the narrative often flourishes in the undefined spaces where his evolution from monster to man intersect in ways that might remind the reader of Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein. This stands out when Monstrilio learns how to speak. As language connected Frankenstein’s monster closer to humanity, it also sways the rest of Magos’s family into seeing Monstrilio’s potential to evolve. While Victor Frankenstein’s creation was an act of pride, crudely cast aside in horror, Magos pours her desire into the lung and focuses on his capacity for good. Like other monster narratives from the genre, Monstrilio plays with the monster’s sense of belonging and maintains a sense of tension in regard to how Monstrilio will be accepted by society but offers a steady foundation of support and love rather than regret and alienation from his creator.

Although their marriage cannot recover, Magos and Joseph maintain a coparenting relationship and are determined to “weed out whichever Monstrilian instincts remained” as they coax the creature into evolving into something closer to human. Córdova packs layers of tension and nuanced emotion throughout the book as we see Magos and Joseph work through the stages of grief, but there is also a sense of loss as Monstrilio is forced to mask or suppress the inhuman parts of himself. This identity crisis is muddled by his name as Magos begins to call him Santiago in public, while he prefers M to distinguish his transformation and personal identity from the idyllic son that was lost. In Monstrilio’s early phase, Magos’s best friend, Lena, admires the monster. “It opened its mouth wide, revealing the fullness of its fangs. Two rows extending halfway across its body. I was jealous of the monster, how it didn’t care what it was or did. No shame. It held itself up with a certain pride.” The balance between fear and admiration for the monster carries across the horror genre, and Monstrilio stands out in the ways Córdova leans into the emotional complexities of the characters’ lives.

The story is split into four sections, each featuring the perspective of one of our protagonists: Magos, Joseph, Lena, and M. While Monstrilio’s transformation and the fear of his inhuman nature is the central tension, each perspective is distinctly personal and introspective, and the text resonates with a longing from each character to be seen, loved, and understood. There is a primal sense of desire that manifests as both hunger and consumption, but also as sexuality, which is a place the characters are often their most vulnerable selves. Our four protagonists are LGBTQ+, but Córdova doesn’t spend his time exploring the build-up to this aspect of their personality as many novels often do. Rather, it is stated as a fact, which was incredibly refreshing to see, and left space to explore nuances of sexuality beyond sexual orientation. This opens the door to kink and fetish as Lena describes how she regularly hires women to bathe her, an act that is both sensual and allows her to explore the part of herself that longs to be cared for. When Monstrilio starts dating, the sense of vulnerability is complex because he wants to be loved and accepted as himself—perhaps not as human, but as the individual he’s grown to be. But despite his best intentions, he is a predator and his desire to bite his partners often toes the line of consensual kink and an act of violence. “I say I’m hungry because my hunger is what makes everyone scared,” Monstrilio notes. He wants to partake in the raw, unashamed, ruthless consumption of a predator consuming prey, but knows if he doesn’t resist the temptation, he can’t maintain the illusion of his humanity or live up to the idealized reincarnation of Santiago he’s meant to be.

Córdova masterfully blends the elements of literary horror and folklore to create something distinctly modern and unique. Monstrilio might not be a typical monster story, but it draws the reader into the fold of a family moving through the stages of grief, and it resonates with hope for new beginnings. Córdova creates a classic sympathetic monster with Monstrilio as he writes him with a deep sense of humanity, understanding, and desire to be good, but also a desire to be his true self. There is a sense of freedom in acting on predatory instinct and giving in to his ravenous hunger because “hunger can be magnificent.” Perhaps the real question Monstrilio poses is not what makes a monster human, but why we would want to change him to fit our mold of humanity.