Late to the Party: A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin

Words By Jaclyn Morken

I’ve been an avid fan of speculative fiction for as long as I can remember, but I’ve always tended to stick to rereading my favorites. The sci-fi and fantasy genres are massive, and I have decades—if not centuries—to catch up on. Sure, I’ve read TheLord of the Rings, but what are the other foundational books in this realm? The game-changers? The “classics” I ought to have read by now? I’m clearly late to the party, but hey, at least I’ve made it, right? Now that I’ve arrived, here are my thoughts on the classics.

***

“The island of Gont, a single mountain that lifts its peak a mile above the storm-racked Northeast Sea, is a land famous for wizards.” – A Wizard of Earthsea

I knew nothing about this series before I picked it up, and little more about Le Guin herself. I’d read one of her series—Annals of the Western Shore—too long ago to remember properly, so I went into this with no idea what to expect. All I did know was that Le Guin was considered a brilliant, boundary-pushing legend in the science fiction and fantasy (SFF) genres. So, I may not have known her work, but I certainly knew her name.

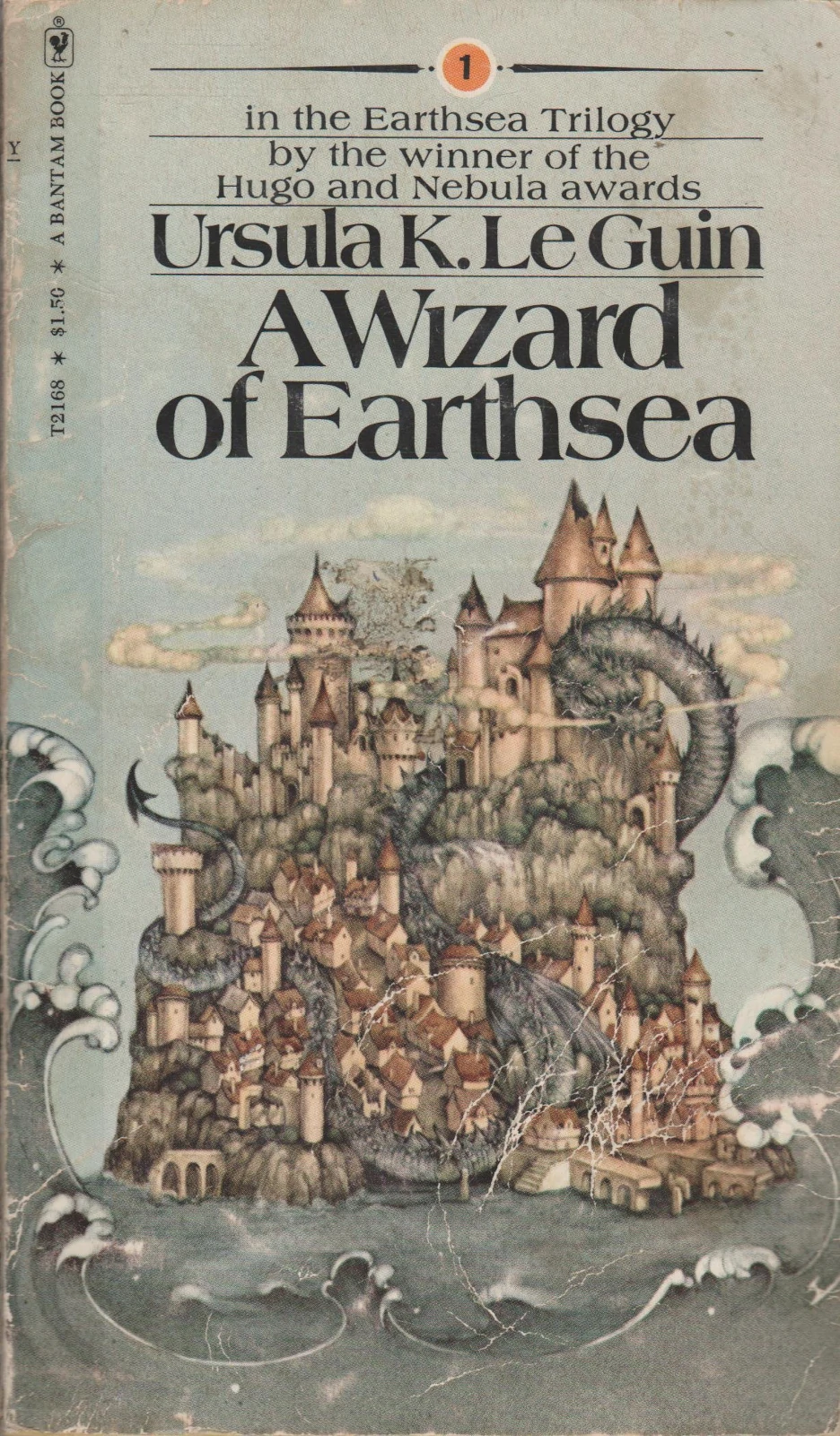

A Wizard of Earthsea was published in 1968, launching a series and career that has had a profound impact on SFF literature over the past fifty-three years—and it’s hard to believe I knew so little about it for so long, given that Le Guin’s influence is so prevalent. For example, some critics credit her for popularizing the “magic school” story long before Rowling. So many of my favorite authors, influencers of my own writing—Rick Riordan, Christopher Paolini, Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman—have acknowledged Le Guin and her Books of Earthsea as favorites of their own. And, in science fiction, Le Guin was a pioneering voice for women; The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) is considered a “breakthrough for female authors,” offering a revolutionary perspective on gender roles and cementing Le Guin’s place in the genre. She amassed a stunning oeuvre of novels, short stories, poetry, translations, and essays that won her dozens of awards, including the Boston Globe-Horn Book award for A Wizard of Earthsea, among many other prestigious honors for SFF writers.

Le Guin’s seminal fantasy novel opens on the island of Gont, in the Archipelago of Earthsea, the birthplace of a boy destined to become the great wizard Sparrowhawk. The boy, whose true name is Ged, discovers his powers at a young age and seeks to realize his full potential, first under the tutelage of the wizard Ogion, then at the school on the island of Roke. In an impulsive display of his prowess in front of a rival student, Ged inadvertently lets loose a malevolent shadow into the world. The shadow knows him intimately and will pursue him to the ends of the world to possess and destroy him. Ged is the only one who can confront and defeat this unnameable evil, and no place will be safe for him until he does.

On the surface, this is a timeless epic tale, a classic Hero’s Journey through the dichotomous battle of good versus evil, light versus dark. A little formulaic, perhaps, but that’s not necessarily a criticism; there are reasons the hero’s journey appears here, not the least of which being that Le Guin was intentionally subverting some of the fantasy conventions she grew up with—as she explains in her afterword to the 2012 edition of the book. Specifically, she says, she questioned the conventions of featuring a white hero—which Ged is not—and using a grand battle to define and defeat the story’s villain. Le Guin pushed past those conventions in A Wizard of Earthsea, adding an unexpected (and thoroughly welcome) nuance to that traditional light versus dark formula: namely, that light and dark exist in balance with one another, and that a person cannot be whole without elements of both.

Such introspective subversion drives the narrative, offering unexpected complexity and realism to this children’s book. Power ought not to be wielded for its own sake, nor is mastery of anything achieved through shortcuts—these lessons are impressed upon Ged as he struggles to control his impatience and pride during his magic studies. But what resonated most strongly with me is the value repeatedly placed on apparent mundanity, and the respective roles all things play to balance the world. Altering even the most trivial of things disrupts the equilibrium and may have untold consequences, and for that reason, everything—rocks, sand, even silence—is equally important. This lends a fascinating dynamic to Le Guin’s world: it is at once complex and simple, huge and small. We learn of the legendary power of dragons and the ancient magic of true-names, but so too do we spend time walking in silence and enjoying fellowship. The quiet, contemplative moments in Ged’s life are just as profound as the grand epic unfolding around him.

As a result, Le Guin does not sacrifice attention to her characters for the sake of the plot—something she discusses at length in her essay, “Science Fiction and Mrs. Brown.” At the heart of this fantastic narrative is a very human story. Ged is impulsive, proud, and prone to jealousy, much of which arises from his humble upbringing and desire for his peers to value him as an equal. He makes a cataclysmic mistake in boastfully attempting magic beyond his abilities, letting the shadow and its evils loose onto the world. The incident leaves him scarred and shaken to his core, and we watch as he must choose between securing his own safety and that of others, pushing him to the brink over and over again. He struggles, triumphs, fails, and doubts. Like the heroes we love in our stories today, when he is rocked to his very foundations, he finds within himself the strength to rise, and grow, and overcome.

I was pleased to find that most of the characters, and the rest of the Archipelago, are not white, which was a welcome surprise from a book published in the mid-twentieth century. I was much less pleased to discover that very few of those characters are women, and fewer still have any significant role in its unfolding—and I’m not the only one. The women of Earthsea remain in their homes, away from the happenings of Ged’s adventures, so I’d hoped to encounter more dynamic women as the narrative progressed. Thankfully, we meet Yarrow of Iffish, the precocious and witty younger sister of Ged’s closest friend Vetch, but even she appears late in the story and stays behind as her brother and Ged depart for his final confrontation with the shadow.

The words “Le Guin” and “Feminism” had always hovered close together in my mind, and I wondered, disappointed, why A Wizard of Earthsea did not seem to meet those expectations—even if the following novel, The Tombs of Atuan, switches to a young woman’s perspective. But I found the answer from Le Guin herself. At the time A Wizard of Earthsea came out, fantasy stories written about women—and unapologetically by women—were unprecedented. As Le Guin explains in her 2012 Afterword, she had to be “deliberately sneaky” with her subversions of the conventional fantasy narrative.

However, as Le Guin explained in a 2004 interview with The Guardian, she was able to bring a new perspective to the later Earthsea books because of her growth as a writer during Second Wave Feminism: “One of the things I learned was how to write as a woman, not as an honorary, or imitation, man.” And, she has said in an interview with Karabatak, reclaiming her own voice in a male-dominated genre enabled her to explore her Archipelago more deeply and thoughtfully, seeing the world through the perspective of “the powerless.” I’m eager to see how the women of Earthsea appear and develop in the rest of the series, as I now feel certain they will.

Reading her interviews and essays, I’m increasingly delighted by Le Guin’s wit, her passion, and her sagacity. She was a remarkable and talented woman, and it’s no wonder her work has had such an impact on SFF literature. After finishing A Wizard of Earthsea, a pleasant enough read that continues to resonate after setting it down, I’m left wanting to read more of her work. Perhaps it’s time to revisit Annals of the Western Shore, or delve into the ground-breaking The Left Hand of Darkness—or stay in Earthsea for a while longer, which promises to get even better as the series progresses. Regardless, I now have a much longer reading list.