Kitchen Table MFA (Dogfish): The Handless Maiden

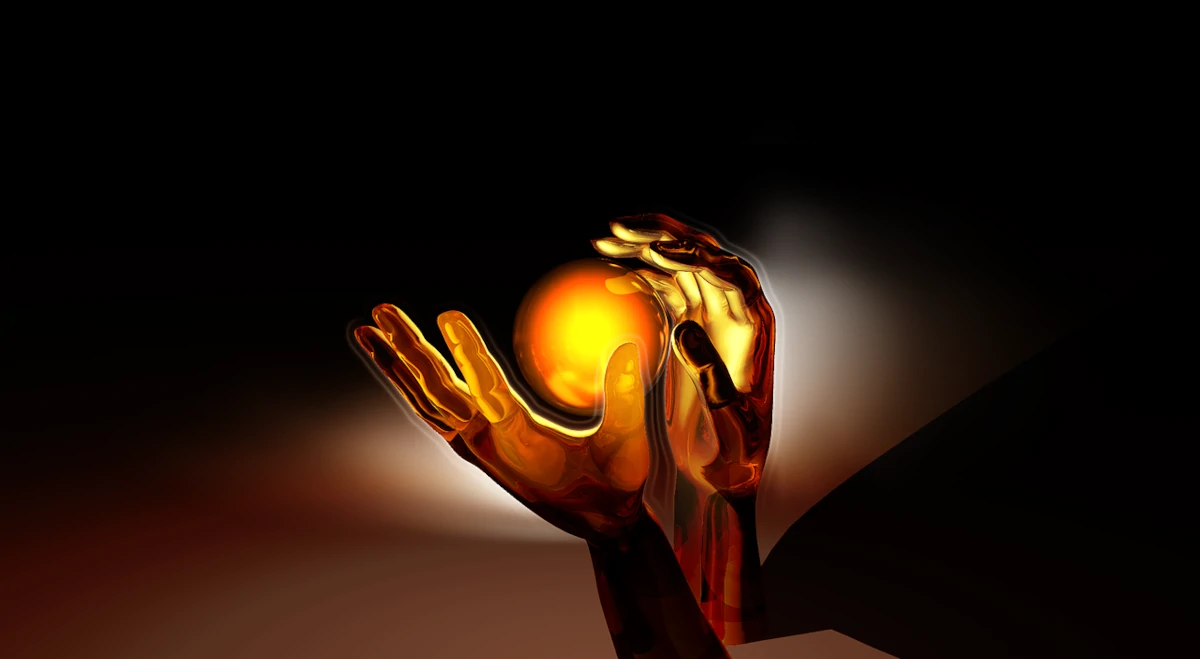

Words By Laura Mattingly, Art By Rafael Zajczewski

This poem is part of the Kitchen Table MFA, a series that showcases writing communities through interviews and creative writing.

I.

Her small hands learn through pleasure

coiling like sea shells’ pale swirls, a shushing,

fumble and feel around.

The textures are a foreign pallet.

Her baby fingers lay like chubby matchsticks—then splay.

They learn what they want

reaching by interest,

survival and self-gratification—thrill of following the tedium to see where it goes—fresh and fantastical.

Touching and touching,

feeling and knowing.

Outside herself

the dry, crumbly-veined leaves,

soft cloud-cotton clothes,

the sharp pain of cold snow.

Inside herself

mysteries, and swamp monsters,

wet branches that gleam,

poke and shake.

Then older, her own worst life-planner,

she makes a bargain in a moment of weariness.

Cut the hands off

and where do the seeds of the story go?

Cut the thought off, amputate its flailing creativity at the base and afterwards asks herself in what soil shall she plant the hands, in what patch of swirling swamp reeds?

Instead of please

she goes walking.

After the ax crosses her wrists, the entire world fills with ringing. The sun knows this. And so does the ocean and every tree.

Feeling with memory, and also, now, feeling with feet. Swinging her stumps in numbed shock between the trees, hair mussed as a quick spring nest. Callousing after the severance from the idea of a whole, a woman is made of many things. Sensitivities and absence, wild patience, haphazard endurance, her parents’ strength and conscience,

and the great alchemy of mistakes,

time makes and makes

II.

Off as in completely gone

Off—how birds swim swirls in the sunset evening at a distance

Off—never again. Don’t even call anymore

Off—in the middle of the river, drunk or very sober, hoping the barge lights don’t just sneak up

Off—more dark than it’s ever been

Off—a free day, time belongs to no one, no need to report

Off—to be, unexpectedly, and despite earnest intuition, entirely wrong

Off—the lover sheds clothes in absolute certainty

Off—departure without expectation of being found, where no one will even look

Off—way out there

Off—you missed the mark, dart hitting wall half a mile from the board

Off—the edge

the glass hydroplaned in a lake of condensation.

Now I’ve make you mad.

Off—the phone goes directly to voicemail

Off—left the room completely, though the light smell of breath probably clings

Off—removal of clothes for the shower, think no one will enter the room now that he is gone, and then dry

Off—my shoes on the ground beside the bed, always get pushed under

Off— turn the knob to the music in summer and hear the neighbors’ roaring chorus of window units

Off—in the distance sailboats seem stale, I can’t hear the canvas flapping

Off—I remove your guard for the first time like a swirl of evening birds taking off, and you smile back without control

Off—the fingernail, now so sensitive I can’t touch anything

Off—the way I pushed into water with no one watching—the way I enjoyed the sun on the water all by myself through an afternoon, curved and waiting. When the rain caught me blinded I laughed and laughed Off—my head.

III.

For three years after I sold myself to the devil

without knowing

I waited without anything but myself, I

cried every day and did not sing.

The river is a slow mirror before its drop

into hell.

The grandmothers gone send me words,

spontaneous sourceless sprouts in my ears at night

you are strong but you have no courage

you are so strong and the strength of your self-hating

negates you

I bathe frequently

I dress in white,

eat raw white onions to singe and scour me out inside.

My safety lies within a thin white line. Circles, well,

they’re perfect—a stick of chalk

traces a small rotation, a thoughtful wrapping.

My dead grandmothers comb my hair.

If I love myself is that enough

to send even the devil himself

back to hell without me on his arm?

His message is this: you will die.

You will die

and your mother and father

your sisters and brothers, they will die too,

and the flowers and trees

and the fields and fields of grasses,

all the thoughts like winding reeds,

all the thoughts, lush, pushed up from the soil,

their green heads spinning—gone—fields and fields

of thoughts felled

every cell in my body yelled and yelled

with wooden marimba-key resonance

though they produced no sound.

Take my hands off—tattoo my face,

free my wrists,

if you want a bargain, I’ll bargain like this

Devil won’t want me without fingers to hold his dick.

I’ll fill my mouth with leaves

and I’ll fill my cunt with twigs,

I’ll fly hell in the sky like a kite

and I’ll bury heaven deep and safe where

no one can touch it.

Won’t be choppin’ no wood no more, no,

no, I won’t be sweepin’ the fallen needles no more,

no.

And her innocence broke up like a boat made of paper,

innocence that had crowded and clouded her eyes.

Now she’ll see everything very clearly for the rest of her life.

No more working.

No more working.

No more working.

She’ll walk around the world dissolving motes with her will,

eating pears that bump her cheeks, reaching

down from their branches.

No more work but walking,

she’ll survive by sight.

She will marry a king who will craft her silver hands

that will shine for the world like

a river mirrors at the confluence of awe,

silver fingers ginger enough to play another song on the piano,

strong enough to strangle the devil or

any bad man.

Read Nancy Reddy’s interview with Dogfish here. Be sure to also read the work of Dogfish member Benjamin Aleshire.