How Memories are a Catalyst for Creative Prose

Words By Thomas Chisholm

As the sum of a person’s history, the foundation of their identity, memories are inherently meaningful. They can be the reason why a person or a character behaves a certain way. They also work as creative vessels for narrative. An author unleashes a memory’s creative power through stream of consciousness writing and a recollected memory splinters the mind into different moments. A light shines on what was once forgotten. The stream of consciousness becomes a series of discoveries. When put to paper, the expanses that stream can cross and connect are endless.

In writing, a memory is a deviation from the forward momentum of a story. When a character recalls the past, an opportunity arises in the narrative for off-kilter prose. The crooked nature of an old memory creates an opportunity for embracing the surreal. The memory-deviation creates an opening for the stream of associations. But stream of consciousness writing takes the reader down a rabbit hole and exhausts them. There’s a fine line between astonishing prose and total self-indulgence. Utilizing it specifically in the depiction of memories prevents the prose from straying into indulgence. Showing a reader how unusual a mundane memory is can help them understand why it’s worth exploring.

Realism, though put on a pedestal, is still genre fiction. It’s often seen as the default mode of writing in literary fiction. We hold highbrow fiction to such a high standard. And as Zadie Smith once so dutifully pointed out: the genre is beyond its saturation point. In both fiction and nonfiction memory can be the vessel that breaks the mundane spell of realism’s supremacy. The past informs the present; deviating away from the main plot into the past is a standard device in storytelling. For the sake of prose, let memory be a way to break the spell.

I’m developing a short story about a kid who attends a funeral for the first time. When he tries to remember the deceased great uncle he barely knew, it comes through a little patchy. I let the memory take on a quality like magical realism:

I’m sitting on the floor with the TV at my back and Hot Wheels in my hands. I look up at the tall adults clouded in a fog of cigarette smoke. Uncle Howard cackles with faceless companions, beer cans in hand, all three of them have slicked over salt and pepper hair.

It’s not meant to be spooky or metaphorical. The memory is fuzzy because the character doesn’t know who the other adults are, and much like a dream, they don’t have faces. I’ve invited the surreal into the narrative and created a moment of intrigue for the reader.

Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, the book our friend Zadie Smith once championed as a better path for contemporary novels, offers a different take on memory writing. In it, a man does everything he can to live his life in memory. He comes into money after a mysterious accident causes him severe brain trauma. He uses the money to recreate and sustain moments that felt meaningful for him. It requires him to buy buildings, renovate them, and hire actors who live in adjacent rooms and rotate through routines. All the while he floats in a euphoric sense of presence, in a reproduction of the past.

McCarthy exploits the absence of the present moment for an entire novel. He scratches a nostalgic itch: what happens when we can get that beloved moment back? It’s deliberately indulgent without being stream of consciousness.

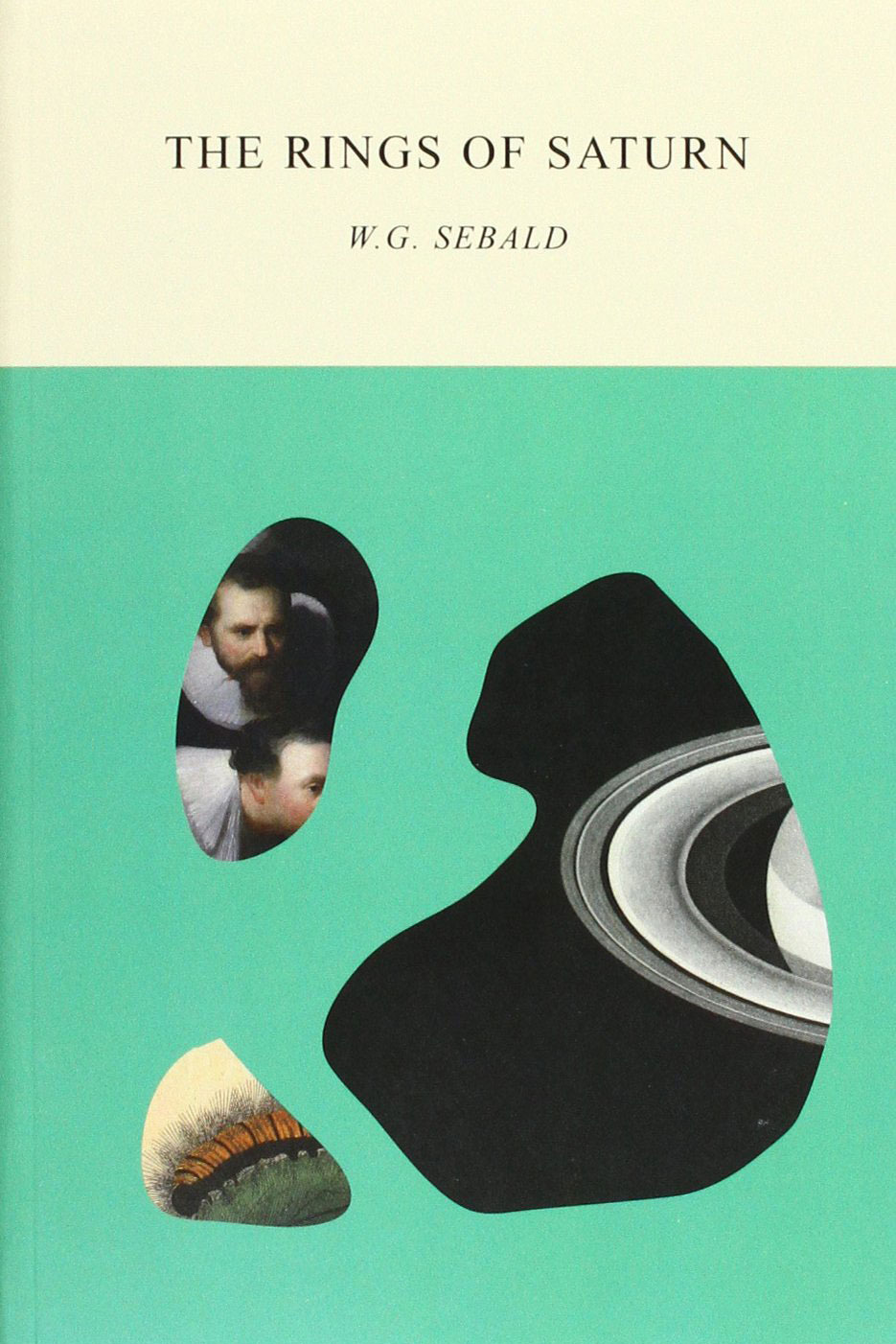

Yet memory’s greatest strength is its associative nature—when it reaches out and brushes up against infinity. Authors use memory as a jumping off point to explore endless possibilities. W. G. Sebald offers an especially associative take on memory writing in his novel The Rings of Saturn. Association writing is how memory enters a stream of consciousness. Sebald tames the narrative impulse to expand outward without end by rooting his novel in a walking journey along the eastern coast of Britain. The Rings of Saturn successfully expands and contracts because it always returns to the same place: a man walking up the coast. In the following section from the novel, the main character sits on a beach and a memory triggers another about a dream:

[T]he storm . . . had broken over Southwold in the late afternoon. For a while, the topmost summit regions of this massif, dark as ink, glistened like the icefields of the Caucasus, and as I watched the glare fade I remembered that years before, in a dream, I had once walked the entire length of a mountain range just as remote and just as unfamiliar. It must have been a distance of a thousand miles or more, through ravines, gorges and valleys, across ridges, slopes and drifts, along the edges of great forests, over wastes of rock, shale and snow. And I recalled that in my dream, once I had reached the end of my journey, I looked back, and that it was six o’clock in the evening. The jagged peaks of the mountains I had left behind rose in almost fearful silhouette against a turquoise sky in which two or three pink clouds drifted.

In this one short section, Sebald blends geography and meteorology with personal experience, dreams, and landscape descriptions. His text creates a moment of dreamlike fusion; a network of infinite connections with unpredictable outcomes, reminding the reader of a world full of connections that we can access at any time.

Sebald’s narrative works so effortlessly because he anchors his ruminative text in a place. By doing this, his narrative can wander as far and wide as he can imagine, and keep the reader engaged, because it keeps returns to the geographic place of the trek. With his place always shifting, Sebald is able to repeat this cycle over and over again until he reaches the end of his journey. The place of Sebald’s text acts as a vessel for containing his associations within.

Without the set up of a walking trip, the novel would be a pulpy mess of freeform associations. Though beautiful and philosophically stimulating, it wouldn’t be much of a pleasure to read. Instead, Sebald gives his readers a tidy box containing the infinite nature of one human’s mind.

If your writing suffers from a lack of ideas, turning to specific memories can help immensely. Memory writing is exploratory and if it doesn’t result in an experimental piece worth developing, it will at least reveal a story worth telling.