Editor’s Note

Words By Dani Hedlund, Art By Various Artists, layout arranged by Ejiwa "Edge" Ebenebe

Dear lovely reader,

You thought this editor’s note was gonna be about comics. But you’d be wrong. It’s about tampons.

Specifically, about the instructions on the back of the tampon box.

You see, dear reader, I struggled to read growing up. The letters were more interested in wiggling around than being deciphered. Phone numbers were impossible to remember. I couldn’t spell anything to save my life. Little b’s and d’s conspired to look identical. Beads of sweat formed on my forehead at the mere mention of reading aloud in class.

Stubbornness became my strongest ally. Dani Hedlund, I told myself, wasn’t going to admit she couldn’t do something, that she had a problem. She was going to be just like everyone else, and even if she wasn’t, if she was “behind,” she was just gonna fake it ‘til she made it.

But having not cracked reading by the age of twelve—and having gotten past the humiliation of being the one kid in my class who went to special ed—I started to think I could just live without the skill all together. My little town was too small and too poor to have a proper special ed teacher, to even know what the word “dyslexic” really meant, so I’d instead been branded with the title “slow.” Well, by the teachers anyway. My peers had other words for it.

So, the game became not about learning to read, but about pretending. I’d mastered asking my dad to read my homework to me at night, memorizing anything I might need to “read aloud” in class. Not to worry my parents, I would sit between them as they read in front of the roaring fire and stare down at my Goosebumps books, carefully turning pages when they did, eyes running back and forth over meaningless words.

And really, the pretending wasn’t that hard. Sure, my grades weren’t great. Despite studying all the time, I lived in a world of Cs. And yeah, I dreaded school, dreaded failing, dreaded the sympathetic looks of my teachers even more than the mockery of my peers, but hell, it was just school. How much did school even matter? Like my parents, I wasn’t planning on going to college. Just the thought made me feel nauseous. No way I’d willingly subject myself to four more years of torture.

But then, everything changed.

In the locker room, I heard about a girl in my class getting her period. And although I hadn’t yet, I panicked. Later that night, sitting on the floor of my parents’ bathroom, I realized my hack of having Dad read things to me wasn’t going to work this time. I remember staring at my mom’s pink tampon box, trying over and over again to make the letters form words, to make those words form sentences. To understand what the hell those sentences meant.

I was so sure they would explain away the horrifying black and white diagrams on the box (so much scarier than the illustrations in my Goosebumps books), that the words held secrets to being an adult, to being independent, that I just couldn’t unlock.

And I started to wonder: How many other things would there be like this? Things I wanted to know privately? Or what about the times I needed to read something, and my dad wouldn’t be there? In a small farm town, we didn’t really have street signs—or, well, streets—but the city, what if I wanted to move there some day? Surely, I would need to read the signs? Figure out which bus goes where?

Soon the tampon box was even harder to read, my tears making the wiggling letters even wigglier. And like those letters, I felt the promise of independence grow blurrier and blurrier… until I couldn’t see it at all.

A few days later, I knocked on my Dad’s office door, where his bear of a body was hunched over the table, glasses slid down, nose nearly touching the fly he was tying. Dad tied the best prince nymphs in town, always eager for a break to take us fishing. But when he couldn’t get away—which was most of the time—he’d sit up in his office and stockpile flies, like a man who longs to travel but can only pack bags he’ll never take to the airport.

“What’s up, pumpkin?” he asked, not looking up.

I don’t know why I didn’t go to my mom about this. It was a girl thing, after all, but my mom was always so put together, never a wrinkle on her pink blouse, never an eyelash uncurled, and I feared that perfection. Someone like me would never be able to live up to that standard.

But Dad? Dad was messy, funny, weird. His hair was always wild, like he’d been driving with the windows down. His Hawaiian shirts were often buttoned incorrectly, flip flops held together with electrical tape. And it wasn’t just his appearance. Dad didn’t think or talk like the other parents. Dad thought Dune was way better than the bible, that lightning storms were better than the movies, that school would never be as important as the Rolling Stones and a great mayfly hatch. Surely, he wouldn’t judge me.

“Dad, I… well, the thing is… ”

“Take your time, kid,” he said, finally looking up to see me blushing. “And hand me some thread.”

“Which color?”

“Surprise me.”

I walked over to the wall of thread spools, all neatly organized, a rainbow of possibilities. Dad knew that always calmed me. The colors. Being creative. Not having just one right way to do something.

He also knew that talking was easier for me when I had something to do with my hands, when I didn’t have to make eye contact.

“I think… I’m… bad at reading,” I finally confessed.

“Why do you think that?”

“Well, the words… I… they don’t stay still. I can’t… I don’t understand them. They hurt my head.”

“All the time?”

“Yeah.”

I heard him lay his tools on the table, click, click, then the creak of his chair as he sat up straighter.

“But your Goosebumps books?”

I swallowed, fingers shaking over a bright yellow spool of thread. “I’m just… looking at the pages.”

“But… you seem to genuinely enjoy them? I’m always looking up and you’re smiling.”

“Oh, yeah… I’m, ah… I’m making up the stories in my head, from the illustrations.”

“But you aren’t reading the words?”

I could feel myself tearing up, shame burning through me. I remember being so sure my dad could see my whole body blushing, the skin on the back of my neck like a red stop light. Turn back. Go no further, the sign said. This girl is stupid. Worthless. Unlovable. Stop before you get tangled in the wreckage.

“How long?” he finally asked.

“For… ever. Always.”

“Hmm.”

I remember how long the silence felt. Endless. Finally, I heard him stand up, walk over. I was too afraid to turn around, to see how disappointed, disgusted, his face would be. Something lifted in front of my line of sight: the nymph he was tying. I remember its fluffy gray body woven around the hook with a little green feather coming out the back, like a bird’s tail.

“What do you think?”

I knew the question wasn’t about the quality of the fly (Dad was the best) but about the color to add next. Fish aren’t entirely color blind, but the conditions of the water affect how their sight has evolved. Freshwater fish, like trout and salmon, can see reds, oranges, blues, and greens, and you want to make a fly that catches their attention.

I looked from the fly to the wall of threads, carefully selecting a burnt orange and then a shimmery, metallic purple. “Orange first, on the body,” I said. “But maybe a stripey layer of purple on the very top? So they get to see the glitter, and we get to see the cool colors.”

“Magic.” He took the thread, and unlike me, his hands were big enough to hold both spools in one hand. “Listen, Pumpkin, I don’t know about the reading thing. Let me think on it. But…” He waited until I looked up at him to finish. “I do know something already.”

“What?”

“You’re not dumb. I promise. It’s like what Mick Jagger said, ‘Different isn’t dumb.’”

A smile cracked on my face. “Did Jagger really say that?”

Dad shrugged. “Probably… at some point. He’s a talkative fellow.”

A week later, I was summoned up to Dad’s office and handed a present. It was summer, but Dad still wrapped it in Christmas paper. Taped to the front was the orange and purple fly with the green tail. When I tore the paper away, revealing the cover of a book beneath, I was instantly disappointed. How in the world did Dad think I’d be able to read this? Was he telling me I was just lazy? That I just needed to practice more?

But then I flipped it open, and there weren’t walls of daunting text. There were illustrations everywhere.

And not the sporadic black and white sketches in my other books, but big, colorful drawings on shiny paper. Some of the illustrations had words in text bubbles or in boxes, but it wasn’t overwhelming.

“It’s called X-Men,” Dad said. Then he leaned behind him to pull out another identical comic book. “I got one for me too, and I thought we could read them and then talk about them. Like a book club.”

“But… what if…”

“It’s okay. The images will do most of the work, showing you what’s happening. But try to work on the words, okay? I think it’ll get easier.”

And it did.

Dad didn’t know any of the amazing research about how comics are an incredible tool for low-literacy and reluctant readers. He didn’t know that the lack of justified formatting of the text makes it infinitely easier for people with dyslexia to read. He didn’t know why I struggled, but he knew that I loved stories, and if I could just find a way to engage with them, to get pulled into the plot and characters, then I would have enough passion to try, to really try, to get past the fear of doing it wrong. To create a system that worked for my brain.

Decades later, when you ask my mom what my struggles with reading were like, she always tells the story of me running through the house, loudly and frantically reading everything—cereal boxes, postcards, the back of her tampon box. That’s always the one she remembers, me standing in front of her in my My Little Pony pjs, reading the entire back of the tampon box like it was Shakespeare.

“It was like a lightbulb turning on,” Mom always says, “and then you couldn’t stop.”

But Mom was wrong. It wasn’t a lightbulb. Wasn’t an “ah-ha” moment. It was a long road. A road paved with brightly colored panels of superheroes. And like my favorite X-Men, Rogue, mastering her mutant powers, it took eons to learn my limits, to practice, to be strong enough to not despair. I learned to look for patterns instead of individual letters, to use the easy-to-identify words (nice short ones) as anchors to more effectively guess at the bigger ones—just as I had used the illustrations to anchor the text in my comics. With a strong coding framework, I could read most words as long as they were in context, even when all the d’s looked like b’s and all the n’s masqueraded as r’s.

But Mom was right about it being impossible for me to stop. Once the passion turned on, I was hooked. For me, reading became a portal to other words, to other experiences. And although it was hard, although it took me so much longer to read anything than my peers, I loved it. Not just to the act of reading. But what it gave me, how it changed who I was. For the first time in my life, I wasn’t the scared one, the quiet one, hoping to go unnoticed.

I was the girl with her hand raised in class, the girl who knew the right answer.

And that became addictive, being good enough, smart enough, knowing things. Not just how tampons worked (which, it turned out, was just as horrifying as the diagrams), but also how the world worked. Physics. Mathematics. Politics. The economics of why “spice” was so valuable in Dune. How Winston Churchill conducted meetings in the bathtub. How hard it was for Banner to control the Hulk. How, in all those stories, a single person, with enough stubbornness, could actually change the world and make it better.

It’s not surprising that I wanted to grow up to be like them.

Nearly a decade later, I sat across from a white man in a black suit at the University of Oxford and finally got diagnosed with dyslexia. I remember his shock, eyes moving from my transcripts to my newly printed cognitive reasoning score. I finally received official confirmation that I wasn’t slow, I wasn’t lazy. My brain was just a bit different.

I remember watching his eyebrows furrow, an unspoken question written in their confused curves. “How in god’s name did you get into Oxford?” those eyebrows asked. But he didn’t ask me. Instead, he took

a deep breath, saying instead, “Of course, reading and numbers are obviously a challenge. Anything with sequencing. But you can avoid that.” He picked up a paper before him, presumably my transcripts covered in firsts. “I assume you’re studying… arts? Painting? Maybe dance?”

I smiled, proud, stubborn. “English, philosophy, and maths.”

He laughed because he thought I was joking. I laughed because I wasn’t.

I was in the last year of my degree, and I’d decided to turn down every smart-move job offer to instead keep running a little dream of a nonprofit. A dream of books and storytelling and people like my dad, who looked past the obvious to find the potential hidden within.

I think of my laughter every time I step into a classroom, comics like the ones you’re about to read tucked under my arm. From low-income high schools to max-security prisons, we use comics to teach low-literacy and reluctant students, from dyslexic kids like me to those who have fallen through societal cracks in far more drastic and heartbreaking ways.

These comics don’t just help improve literacy, critical thinking, and communication; they can give us the biggest and most important gift of all: the ability and desire to change the story we tell about ourselves. To be heroes in our own narratives. To discover our own superpowers, to nurture them, to develop the resilience and stubbornness to fight for our future, even when the world tells us we don’t have what it takes.

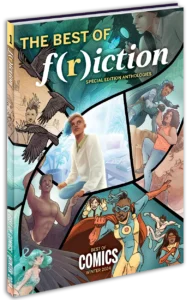

In these pages, you’ll find nine amazing stories that do just that: make us think differently about the world. All of these works were first published in Brink’s publishing imprint, F(r)iction, a collection of amazing stories, poems, essays, and comics that we teach in all our nonprofit education programs. Spanning nearly a decade of publishing, these original short comics are our favorite and most effective teaching tools, helping students think differently about themselves and the societal norms that try to shape us.

Some stories are fantastical, saturated in family curses, apocalyptic worlds, long journeys to the stars. But, like the X-Men comics I first fell in love with, real themes and hard lessons live beneath the fantasy. Characters explore the difficulties of accepting their bodies, of finding hope in the darkest times, of letting go of the past to carve a new future. We see how caring more about success than the people around us can transform even the strongest hero into a villain, that fear can erode the good in our lives, that accepting our flaws is the only way to embrace our strengths. Others are steeped in reality, like the comic memoir that closes the issue. “Brilliance” came out of our Frames Comic Program, a story from a formerly incarcerated student who spent nearly a year reading and discussing comics with us as he sculpted his own powerful memoir.

For the comic lover, you’ll see some big names from your favorite comics and novels, but the majority of these stories are from emerging and debut talent. New, brave creatives whom we’ve mentored to make sure that the next generation of readers can be inspired by diverse, incredible voices.

I hope, as you read these stories, that you think of your own story. Of the decisions you’ve made that have created the person you’ve become, both the good and the bad. I hope you embrace the parts of you that you love and have the courage to acknowledge and accept the parts you don’t. And remember, above all, that you have the power to decide who and what you want to be. We might not have mutant powers, but we are all powerful. We all have unique talents and perspectives, and we can do truly incredible things with them.

And when in doubt, remember what Mick Jagger probably never said: “Different isn’t dumb.” Different can be a magic all on its own.

Dani Hedlund

Editor-in-Chief