Editor’s Note

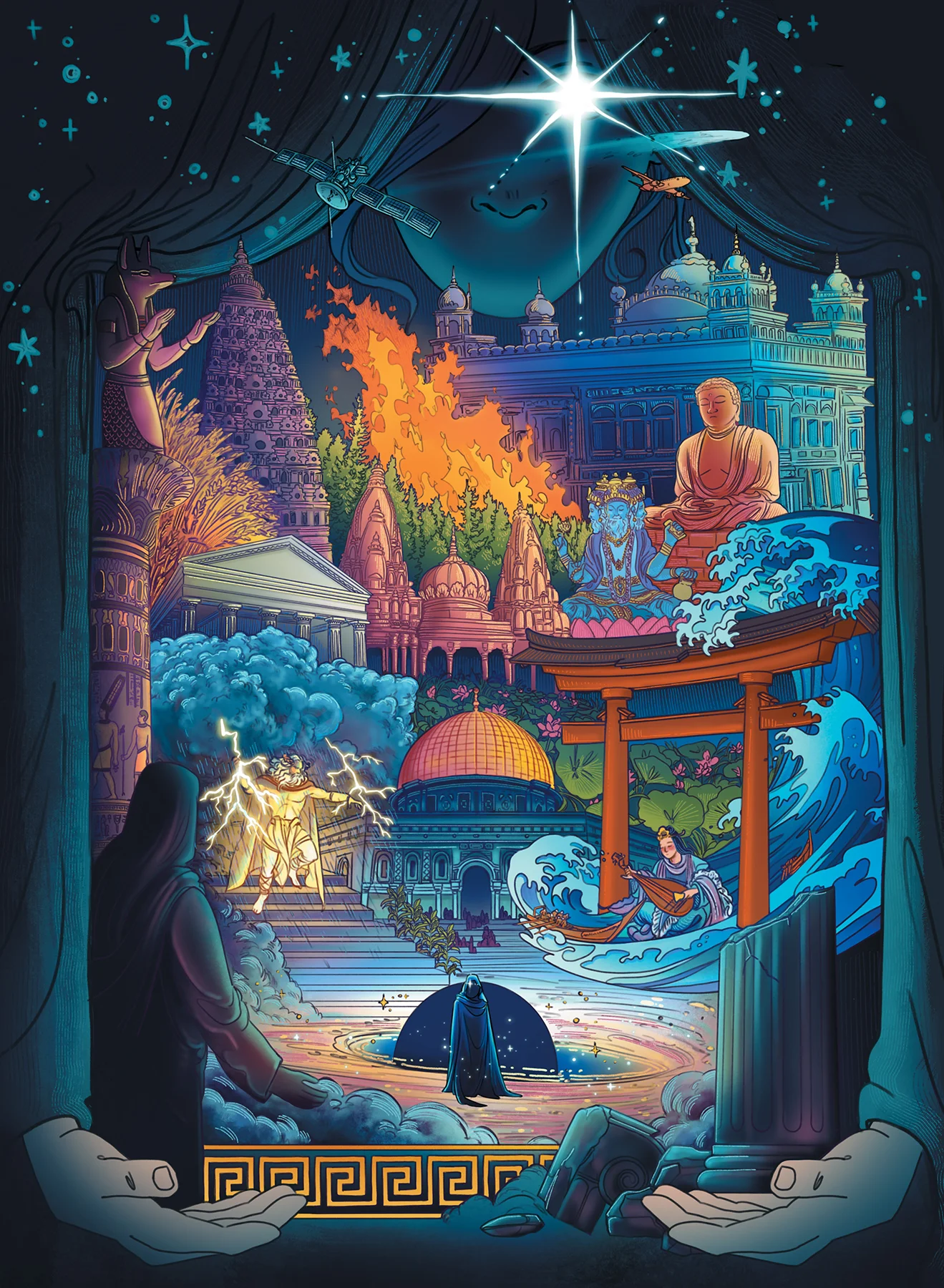

Words By Dani Hedlund, Art By Kayla Rader

Dear lovely reader,

To understand our fascination with gods, please step with me into this handy-dandy time machine I’ve conjured. We’ll press a few impressive, sci-fi, glowing buttons—beep-boop—and gasp as the metal craft shakes, hurling us back in time. Three thousand and twenty-four years fly by—and many, many miles, depending on where you’re cracking open this tome—and we’ll step out onto the dusty roads of Ancient Greece.

At this time, Athens is the peak of civilization (in the West), the birthplace of society, of democracy, of philosophy. Sure, the Indus Valley and Mayans were arguably more technologically advanced (thank you, actual flushing toilets and intensely complex timekeeping!), but what was special about the Greeks is that they were one of the first civilizations that wanted to find answers to everything, from how the elements mixed in our bodies to where knowledge comes from. They were thinkers, philosophers, scientists, sociologists, psychologists—all the things we hail as highly intellectual, highly grounded in fact and method. And in terms of lasting influence, man, they kicked ass and took names. Everything from modern-day democracy to the first concepts of atomics (the idea that stuff is made of littler stuff that we can’t see) and heliocentrism (that our planets revolve around the sun) was influenced by these toga-clad thinkers.

But at the same time as this science was on the rise, faith—what we’ve been told is the antithesis of science—not only thrived but also was needed to make everything else work.

For example, let’s strap on our sandals and wander up the rocky pathway to the Parthenon. It’s not in ruins.

The roof is intact and painted gloriously. The Ottomans haven’t used it to store explosives that “accidentally” go off. It’s beautiful, a sixty-two-foot-tall acropolis overlooking the city full of sun-bleached roofs.

Rain starts to patter on the stone. A storm is coming. Now shudder with me as a bolt of lightning blazes through the sky, scaring the bejesus out of us both. Someone beside us mumbles, “Zeus must be angry.”

Our modern-day brains are tempted to judge this person. Surely for such an advanced civilization, a big old shirtless god in the sky tossing lightning bolts feels foolish… but let’s think about where science was at the time.

Advanced as they may be, the Ancient Greeks have no understanding of weather patterns, of the cool air in the clouds that conjures rain, of colliding positively and negatively charged particles creating flashes of light to carve open the sky. They know only what they can observe. They see enough to know there are four seasons but not why some years are wetter than others. They can observe a healthy body corrupting, but they have no microscopes, no way to understand the many, many ways we can decay on a cellular level.

You see, the Greeks are smart, they are method-centric, they believe in logic… but when there are that many question marks, logic simply doesn’t cut it.

Without modern-day physics, chemistry, astronomy, if you look at the sky broken open by a bright, blinding light and a crack so loud it shakes your bones, what explanation makes more sense than god?

And, for the Greeks, a whole pantheon of them! Don’t understand the movement of the sun? It’s Apollo, dragging the sun along behind his chariot. Are your crops doing better than your neighbor’s? Well, Demeter just likes you better. Are you struggling to get pregnant while your sister can’t seem to stop? Better get your ass down to the temple and pray to Aphrodite.

Like the Greeks, most ancient civilizations used gods to explain natural phenomena that people could observe but not fully understand. Gods, you see, have always been a convenient Band-Aid we toss over anything we just don’t understand. But more than that, in Ancient Greece, science and religion are, in many ways, one. They aren’t competing for dominance. Instead, they team up to explain the biggest, most complicated elements of our world.

But, of course, like any powerful coupling, science and religion were bound to break up.

Now let’s jump in our time machine and cruise forward to the first century CE and the birth of Christianity. For anyone who’s studied the history of religions, you’ll be sick of talking about how much Christianity disrupted the entire field, but think about it: before Christianity, almost all the major faiths’ pantheons— certainly, Greek, Roman, and Norse—all had warrior gods, gorgeous, sexy, capricious bastards who only took a shine to the most magnificent of mortals. The Achilles and Minamoto no Yorimitsu of the world. The 1% of the 1%. Only they mattered to the stars of the big soap opera in the sky.

Those religions, dear reader, were not made for the masses. They were made for the few. Not everyone, after all, is invited to dine forever in Valhalla.

But then, here comes Jesus, who loves you just the way you are, every last one of you. And you don’t need to be great—in fact, being great might be quite bad for you. The meek, he tells us, will inherit the earth.

Judaism, Islam, Sikhism, and Christianity all share this ground-breaking idea of a God who loves anyone, anyone, who is devout, who follows divine laws, and who loves and celebrates their religious values.

These religions no longer try to explain natural phenomena, largely because society was starting to get a grasp on them. During the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods, science had at least some explanation for the movement of the stars, for weather, for the human body. Certainly, it wasn’t always right—Earth as the center of our solar system, leeches pulling toxins from the body, flies spontaneously manifesting—but an authority figure could stand before you and deliver an explanation that lined up with your lived experience.

Instead, the question mark centered on the unseen world: Do we have souls? Where do we go after we die? How should we live?

And man, oh man, did the birth of modern-day monotheistic religion tell people all those things and more. Not just how to live and die, but who to love, who to hate, who was worthy of forgiveness, and who was too far gone. Across the globe, religion became one of the most successful forms of government, of community, of moral order.

And suddenly, the days of the Greeks were over. Faith and science didn’t work hand in hand to help us understand the world. They were enemies, destined to battle it out to the end. And so began the wild escalation of murdering scientists and philosophers. Of “Us versus Them” thinking. Of holy wars and the massive, massive, money-making machine of the church.

Let’s skip over the dozens of centuries of religious wars and blood-soaked battlefields and cruise right back to the modern world of Starbucks caramel macchiatos and smartphones. Statistically, in the West, religion is losing its hold. In America, less than half the population reports being religious, with 20% considered devout, weekly churchgoers. Europe is even lower, with only 40% identifying as religious.

Every decade, these click a little further down.

Of course, there are strong exceptions beyond the West, with South America, Asia, and the Middle East still largely identifying as religious, but from the places where most of us are reading this Editor’s Note, it certainly looks like science is winning the war. And that a deep exploration of gods—say, in a lovely little lit anthology like this one—is growing less and less relevant with each passing year.

But, let’s face it, I just accidentally wrote four pages about the history of gods—and I’m not even at my favorite part yet! Because no matter what the stats about the decline of religion tell us, we are, as a people, fascinated by it. Look at the best-selling fantasy novels of the last fifty years: Circe, Percy Jackson, The City We Became, Dune, Good Omens. We are fascinated by the idea of the divine, from police procedurals starring Lucifer to Bruce Almighty generally sucking at playing god.

So, as with all issues of F(r)iction, we listened to our readers, our students, and our own passions, and started putting out calls for submissions about gods. As a lover of world religions, I expected lots of retellings, wild fantasies where old gods try to walk among us. Or perhaps new gods who mimic what we fret about today, Gods of Instagram and our nightly worship in front of our God of Televised Entertainment.

But like every issue, I’m always surprised by what our community conjures. A first glance at this content will show a big fascination with death—in many ways, a question mark that makes even the most devout Christian or fervent atheist hold a sliver of doubt. From a ride-share app for ghosts to complete their “unfinished business” to a pastor using crazy sci-fi tech to find a way to die that won’t destroy the faith of his flock, death was everywhere.

It’s even seeped into our “In-World Interview,” in which bestselling author Neal Shusterman is interviewed by his own characters from his Arc of a Scythe books, a rad sci-fi series in which a god-like AI has cured all the world’s woes, including death… but in a world without death, someone needs to keep population growth in check, thus introducing a world of modern-day Gods of Death who can “glean” a select number of the immortal humans.

There were also far more works rooted in modern-day Christianity than I expected, including creative nonfiction grappling with the guilt and pressure of standing strong in that remaining 20% devout church demo. We’ve got poetry, essays, and stories that bravely explore contrasting belief systems and how damn hard it is to balance joy and obedience.

And, of course, there are some profoundly hilarious pieces too. I’m particularly tickled by the opener feature by F(r)iction alum K-Ming Chang, exploring how gods evolve to stay relevant, and an utterly fantastic comic by Kieron Gillen in which two tech bros try to disrupt the oldest industry out there… badly.

However, of all the pieces in this journal, the one that takes gods and makes them so deeply human and relatable for me is “Good as God,” a comic memoir from one of our justice-impacted students.

You see, when this theme was just a random thought, I brought it up in one of our Frames Comic Program courses last year. We were teaching a class for formerly incarcerated and justice-touched folks, particularly those with felony drug charges. As it turns out, our students spend a lot of time thinking about God, not only because many of our students are religious themselves, but also because selling drugs is its own form of god-like power. Many of our students were high up in the trade—big money, big influence, lots and lots of worship by their communities… and goodness me, does that sort of power leave a mark.

The class discussion was a Great Flood of questions: How do we redefine ourselves without this power? How do we fight the temptation to go back? How do we accept that there is something or someone bigger than us, and will that make our lives better?

And as our students started delving into their own turning points—moments in their lives when their choices most deeply impacted the trajectory of their lives—one of our students, Jaron, was particularly drawn to the theme. You see, Jaron was writing about growing up in his father’s drug empire, but he was struggling to really land what it was like to feel so in awe of that power, so taken by it even when it killed those he loved.

I won’t ruin the memoir for you, dear reader, but as one of his teachers, I can tell you that the lens of Greek mythology finally helped Jaron express what it was like to be split between his father’s powers and his legit family, a demigod torn between two worlds.

And as I watched Jaron and the amazing artist, Shan Bennion, bring this memoir to life, I thought again and again of that time machine we traveled in. Of the question marks in my students’ lives that they needed gods to answer.

In fact, in all the stories, essays, and poems in this issue, that same lesson applies. Gods—whether of a mystical power source or the power we find within our mortal reach—are still the go-to answer when we can find no other explanation. When our senses fail us. When logic breaks. When the microscope just can’t zoom in anymore. When there is a question mark, God lingers.

And as you read these stories, looking for the question marks in each work, wondering about the question marks in your own lives and experiences, I wanted to leave you with one last mini-jump in our time machine… This is only a wee step back, to the 60s.

Science is having one hell of a heyday, the world marveling as science fiction finally becomes fact. We’re sending people to the moon, “discovering” quarks, inventing things that will shape our modern world: weather satellites, video games, robots. And, as a result, religion is starting to get pushed around. Creationism starts to be replaced with evolution in school curricula, and the world starts to change.

But then… something happens. A crack in the trend.

It starts with the split electron study. For those non-science nerds out there, this theory purports that an electron can exist in multiple states (wave and particle) until it is observed. If you haven’t heard of that, you’ve surely heard the thought experiment that popularized it (Schrödinger’s Cat, in which a cat and some murder toxins are put in a box… and until we open the box, the cat is both alive and dead).

Now this might seem simple, but this idea—that something needs to be observed to actualize—is actually pretty earth-shattering.

Now, of course, most people believe in the Big Bang. Hydrogen, helium, and lithium collide in the universe, and suddenly, stuff exists. Atoms, elements, planets… life. It all appears as a powerful chain reaction, when just a millisecond beforehand, we had empty space… certainly there was nothing “conscious” kicking around in that oblivion. Something from nothing.

If we are to believe modern-day science and accept two facts: one, that the Big Bang happened, and two, that everything needs to be observed in order to happen… there seems to be only one explanation.

Something with consciousness needed to exist when there was nothing… and this thing needed to “watch” the Big Bang happen. But science has no way to explain what or who that thing is.

You see, dear reader, another question mark formed in some of the most advanced scientific minds… and we all know the best fix for a big, old question mark…

So, science invented a “first observer,” some being that witnessed the start of the universe, somehow living outside of time and space (sound familiar, dear reader?). This theory, that observation is needed for everything to transition from the “possible” to the “actual”—called the Copenhagen Interpretation—is currently the most commonly adopted explanation by the scientific community to explain how the quantum realm functions. Think about that. The smartest, most skeptical minds in the world, with the most knowledge, openly adopt a theory that needs a “first observer” to work.

Reminds you a bit of our first time-traveling adventure, does it not? When we looked up at the cosmos from Ancient Greece, and lightning couldn’t be solved just with science or religion… we needed both.

And as you read these amazing stories, dear reader, I hope you remember how much humanity’s question marks have changed… but also, how much they haven’t. And I hope you discover your own question marks and think about how you best can find those answers.

Cheers,

Dani Hedlund

Editor-in-Chief