Come to Mars

Words By R.A. Roth, Art By Tyler Young

Ted lived in Blandville where everybody was so bland and inconsequential they left no impact on anything or anyone. He and his wife, Belinda, had two children, Kid A and Kid B, who, like all Blandville children, were part of an endless procession of stupefied expressions and bland tastes repeated infinitely. They all ate the same sugary breakfast cereal, packed the same sack lunch, went to the same brainless movies made by talentless hacks who prided themselves on churning out garbage, watched the same reality TV shows that were secretly scripted and edited to infuse false drama into the bland proceedings, and listened to the same bland pop songs set to the same bland prefabricated beat.

Belinda drove Kid A and Kid B to school. She sometimes wondered if she should have drowned them in the bathtub when they were little. That solution was off the menu now. Kid A was a brown belt. Kid B could lift a block of cement over his head. Belinda sat in the car and watched them enter the building, then realized her eyes had locked onto somebody else’s kids dressed in the same clothes, the same backpacks slung over the same shoulder, the same trudge toward oblivion written in every tortured step.

Nobody in Blandville was left handed. Those who exhibited signs of left handedness were turned over to the Blandville Commandant for reeducation. The program was simple and effective. They tied the left hand behind their back and made them do everything right handed. In time, the kid learned to be right handed while also learning to hate their parents and plot their destruction, although subversive thoughts never manifested in Blandville given the inherent blandness of the plotters.

Murders were rampant, however, because guns were in ample supply. Murderers, when confronted with their crime, offered up the same bland excuses. I was upset. It was just an accident. I didn’t realize it was my wife/husband returning from a jog. A toddler found it, and it just went off.

The Blandville Police killed people for nothing. Jaywalking. Traffic violations. Looking funny. The citizens of Blandville tolerated it because they were taught to obey and worship authority figures.

Kid A and Kid B were murdered by the BPD for walking on the right-of-way, and something inside Belinda shouted for joy. They were monsters, she thought. I’m a monster for celebrating their death.

Ted didn’t know what to say to his wife. He was too wrapped up fighting back his own inner demons, telling him to get his gun and end her then end himself. End all the blandness, see it burn in a hail of spitting lead, sparks and fiery doom. Bathe the bland world in a crucible of cleansing fire. Start anew. A brave new world of bland souls blandly rocketing through the void in bland concert.

Safety off, Ted put the gun in the middle of the front yard. It was his singular hope that a random child, mistaking it for a toy, might pick it up and discharge a round or two that would do the job Ted was too cowardly to execute. Outsourcing your demise was the Blandville way of doing things.

To fill the void left by the absence of Kid A and Kid B, Belinda and Ted went to a bland movie. The theme was focused on the human condition. They left thirty minutes in, for they knew what it was like to be human and feel unmoored from humanity, to feel disassociated from each other.

They were strangers on a train headed for a mass grave.

Locked in a cattle car, they stared at filthy walls smeared in the fears of the last load of disposable tools.

All I want is a way out, Ted thought, and Belinda looked at him with a flutter of tears in her eyes, the tears of mortality streaking down from the rafters of uncharted ruin. Ted pounded on the cattle car door stained with regret and rejection. “All I want,” he said, heaving his next breath as though it were his last, “is to have a drink beside a pool and watch the sun set like an orange tablet sinking in cosmic blue paradise.”

Belinda said, “Can I come?”

“No,” he said, palms spread against the pebbly surface of emotional extremes, noting regret had encompassed rejection in a continuous plane of unabated anxiety that infected his bones, softened them to loam. “This is a solo journey.” Ted leaned around to look at Belinda. “They all are.”

“All right,” she said and crushed her expectations into a little corn kernel dancing in hot oil, on the cusp of fulfilling its utmost purpose. “Why are we like this, Ted?”

“We are as we were made, Belinda.”

“I don’t believe that, and neither do you.”

“Don’t tell me what I believe.”

“Too late for that,” she said. “Your mama and papa beat me to it. Mine too. They rode this train before us.”

“But we couldn’t see the train.”

“You can’t see it until you’re old enough.”

“I’ve always been old enough.”

“It’s all relative, Ted. What should I do after you depart?”

“Do what you think is right.” Ted slid open the door and leaped into folds of darkness.

Belinda whispered, “There’s no right about it,” and shut the door.

The Blandville Gazette ran a bland obit heralding the demise of Ted Donasso. He was born on month/day/year, died month/day/year of complications due to extreme blandness. Ted is survived by his wife, Belinda Donasso. The Donassos request that in lieu of sending floral arrangements please make a donation to the Foundation for the Cure of E.B. Thank you.

The turnout for the funeral was average.

The preacher stood before the body lying in state and said, “Here lies a good man who went too soon. He was the epitome of everything Blandville stands for. Truth, justice and the Blandville way. Excuse me if you’ve heard that before. Fresh, original eulogies are rarer than virgin births.”

Belinda commissioned a gargantuan monument carved into Ted’s likeness, to serve as his grave marker. The tallest in Blandville Cemetery, it stood six inches taller than the monolith dedicated to Tony Blank, Blandville High School football star who died tragically in the final game of a season in which the hapless Blandville Vanillas posted a record of one and ten. The one win came about when crosstown rivals, the Blandville Pastepuddings, were forced to forfeit after the team came down with a case of the trots from eating at the Blandville Smorgasbord. The culprit was a chafing dish of bile and recriminations. Tony Blank’s premature demise constituted front page news in Blandville. Rocket attacks in the Gaza strip were relegated to the entertainment section. Affairs of state were conspicuously watered down to small hunks of easily digestible information that conformed to the malnourished constitutions of Blandville’s sickly citizens.

“Bland news and weather on the ones,” Blandville radio station, BLND, boasted, and the radio blared patternless bleating shrieks of static the citizens interpreted as secret messages from dead relatives.

Belinda listened and heard Ted instructing her to build a rocket ship to Mars cobbled together from miscellaneous flotsam strewn about the garage, plywood scraps, rusty nails, split bricks, holiday lawn ornaments, and warped boxes full of battered toys Kid A and Kid B stopped playing with once they were old enough to set fires and bully elderly citizens into emptying their purses or endure a quick shove over the railing of the small footbridge, which overlooked a cold muddy stream teaming with mutated fish capable of chewing off limbs and gobbling out eyeballs.

“Look there,” Kid A would say and nod downstream at the morbid scene they’d staged, a clutter of derelict walkers clogging the shallows along a muddy bank, and without protestation the elderly victim would hand over the last dregs of their dwindling pension, and Kid B would bark his satisfaction and miscount the haul to deprive Kid A of his fair share of their ill-gotten gains.

“Why Mars?” Belinda asked, and from the steady barrage of static Ted responded, “Mars is a gulag for the dead. I’ve been locked in solitary confinement for a million years.”

“You’ve only been dead a year,” she said, waiting for the light to change from impassive to petulant.

“Time moves differently for the dead,” Ted explained above the electric hiss. “A second can move as slowly as a decade. A year can flit by as rapidly as a second. In the end it adds up.”

“How else are they treating you?”

The light changed and Belinda gunned it. Tired squealed and metal crunched as death was dealt to random strangers in the rearview world. Kid C and Kid D, orphans she agreed to foster, were in the back seat playing with a loaded, masterless instrument of doom with a hair-trigger.

After the commotion allayed, Ted elaborated his situation.

“Once per day a man stands outside my cell, teases a key into the lock, and tells me if I answer one question to his satisfaction he’ll release me. The question is invariable. ‘In life were you a good person?’ If I say ‘yes,’ he replies, ‘If you were so good, how come you wound up in there?’ and he leaves. If I say ‘no,’ he replies, ‘Then you are where you belong,’ and he leaves. If I answer ‘I don’t know,’ he replies, ‘I do,’ and he leaves. If I say anything else or nothing, he leaves.”

“Does the man have a name?”

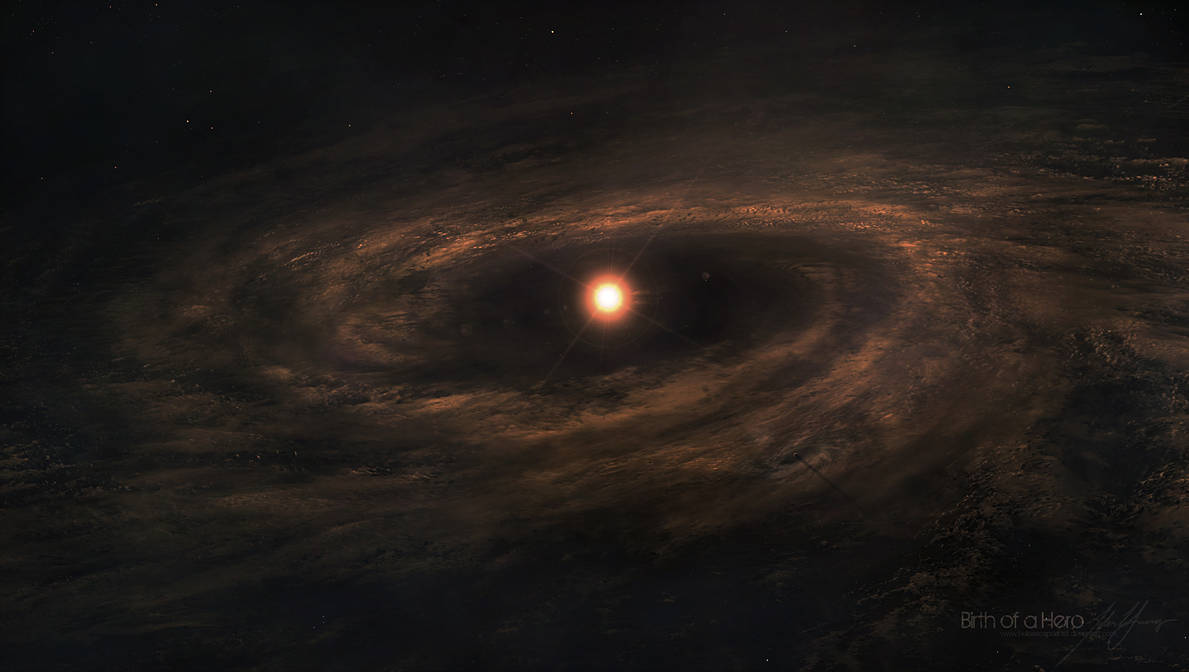

“Ted Donasso. I have always been the man and I always will be the man. I must die so I can live again. Come to Mars and kill me so I can rediscover myself and rise from the red dust, triumphant.”

Belinda shut off the radio and stared threateningly in the rearview mirror. “Kid C, put down the gun this instant. Don’t you look at me like that, you’re gonna get it! It’s Kid D’s turn to twirl the gun.”

“Why can’t we each have one?” Kid C lamented.

Belinda aimed the car for the heart of a traffic snarl. “We can’t afford it,” she said and mashed the accelerator, merged with the congested intersection in a symphony of shorn metal and fiendish screams, for it was all coming to its predetermined end, the final chapter written boldly upon the pages of her life, that she, in the tradition of all Blandville residence, would self-destroy….

Red.

So much red it sears Belinda’s eyes to squinting grommets through which she soaks up the implication of her surroundings in scribbles of pervasive panic. The question “where am I?” rises from the vacuum of confusion, then is instantly dissolved in stark realization. She’s in a prison cell on Mars where a woman (she, it is herself, Belinda Donasso) will come to the door every second, every million years, every increment of time imaginable and ask her the same question in infinitely unwavering, monotonous iterations. She waits for her first foray into this diabolical excursion, ticking off the moments inside her head, picturing a clock face, the thin red hand sweeping the cheeks, first left then right, every thirty seconds until the dry snick of metal violating metal jars her from her trance.

Belinda hears the question, “In life were you a good person?” as clearly as though the woman, herself, were in the cell with her, breathing its poison into her ear in ugly ringing huffs of resplendent accusation, and she thinks on it for a second, a million years, then answers, “Yes and no. As we are ambiguous beings, neither wholly good or evil, this is a fair reply to your inquiry.”

The snick of metal uncoupling from its counterpart resounds in the cell, and the woman, herself, leaves.