Beyond the Waterline

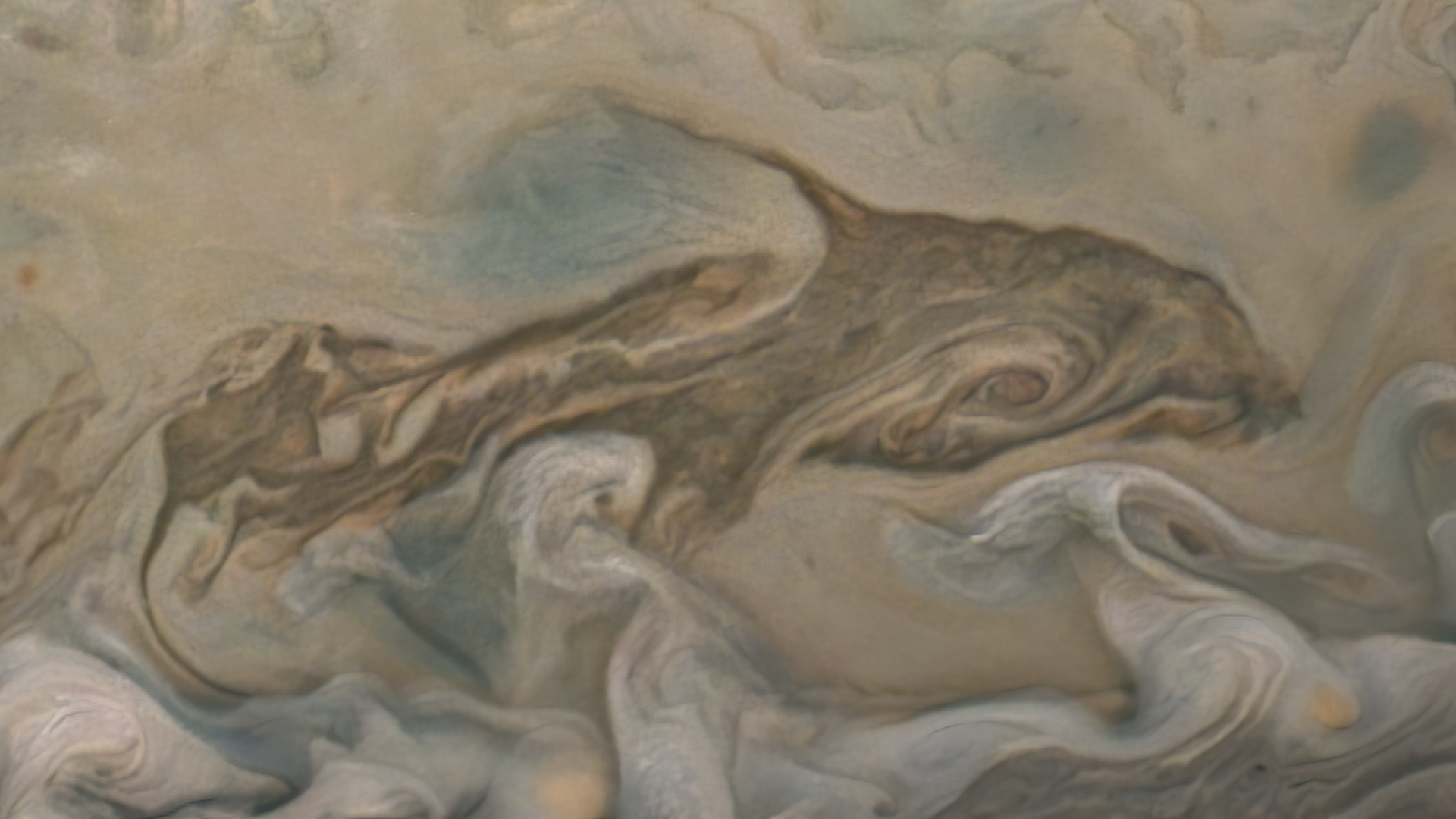

Words By Lisa Beebe, Art By Kevin M. Gill

Tania slipped off her shoes and sat on the edge of the dock, lowering her bare feet into the water. She faced west, toward where the marina opened into the ocean.

A movement in the distance attracted her attention. Was that dark spot a fin?

A few seconds later, a dolphin surfaced next to her. It had a scar over its left eye—and a plastic water bottle in its mouth. The dolphin tossed the bottle onto the dock and swam away.

Tania grabbed the bottle before it could roll back in. It was dirty, dented, and most of the label was gone. She carried the bottle with her as she headed to the ticket booth of the parasailing company where she worked as an assistant and photographer.

She told her boss, Ed, about the encounter.

“I bet it was trying to play with you,” he said, sliding open the metal gate above the ticket counter.

“Maybe,” she said, but the dolphin’s behavior hadn’t felt playful. It felt purposeful in a way she wasn’t sure how to explain.

As a kid, she’d watched The Little Mermaid over and over, wishing she could talk with sea creatures. Over the years, she’d streamed countless ocean documentaries, but they offered mere glimpses into how the animals communicate. She’d planned to study marine biology in college but hadn’t been accepted into the program. The parasailing job wasn’t a career, but meant she could be near the water every day. It never quite felt like enough, but it was something.

A family of French tourists arrived, and Ed greeted them with an enthusiastic “Bonjour!”

On days when the ocean was relatively calm, parasailing tourists might see dolphins leaping through the waves or a school of manta rays swimming just beneath the surface. In the off season, they might get lucky and see a pod of migrating whales. When the water was rougher, they wouldn’t see any animals—just waves and waves and waves.

First-timers were usually nervous, but once they were up in the air, almost everyone found the experience peaceful and relaxing. Tania had been up a bunch of times. With a two-person harness, she had to go up with odd-numbered guests, Ed steering the boat and taking the photos.

The French family’s outing went smoothly. As Ed steered the vessel back toward the marina, Tania asked if they had spotted anything exciting from the air. The girl, Celine, told her in decent English that they’d seen a bunch of “flat fish swimming toward the beach.”

Tania knew she probably meant “stingrays swimming along the shore,” but she didn’t correct her.

Back on shore, Tania walked to the nearby minimart to grab a breakfast sandwich before the next set of tourists arrived. She overheard a surfer telling the cashier, “The beach is a mess, man. It’s covered in trash. Jet stream must’ve shifted overnight or something.”

Tania had seen that happen once before and she didn’t understand what caused it. One day, the beach was clean, except for a cigarette butt here and there, and the next day, there was garbage everywhere—old candy wrappers, plastic bottle caps, disposable cups, potato chip bags… Even after the sand-combing machines had raked it up, the mental image of the trash-covered beach haunted her.

She wondered if the parasailers had seen the mess from the sky. They hadn’t mentioned it, so probably not.

Three college girls from Kansas arrived next, and Tania went up with one of them. The girl gave an ear-splitting shriek when the parachute yanked them into the air.

As they climbed in altitude, Tania was surprised at how much trash she could see on the beach. She also saw loads of rays, dolphins, and sharks. Like the French girl had said, they were all moving either toward the coast or away from it instead of in the usual channels parallel to the shore.

The college girl didn’t know she was witnessing anything unusual. She took photos and videos with her phone, and exclaimed, “This feels so California!”

Tania retrieved her own phone from the inside pocket of her life vest to capture the animals’ behavior. Maybe the same tidal shift that had dumped all the trash on shore was affecting the sea creatures, too.

She racked her brain. Was there a type of seasonal algae or migrating fish on which they might be feeding? It bothered her to see the animals acting so strangely.

By mid-afternoon, news teams were reporting live from the trash-filled beach.

Nobody wanted a sunset flight over the garbage, so after work, Tania drove home feeling anxious. She heated some leftovers for dinner, watched half an episode of a forgettable sitcom, and fell asleep.

The next day, she arrived at the marina as usual and was surprised to see plastic trash all over the docks. She walked up to the beach to see how things looked there.

The sand near the high tideline was completely covered in trash. If she hadn’t worn sneakers, she would’ve had to turn back.

She stepped onto a layer of trash and heard the hollow crunch of a plastic bottle flattening beneath her. Walking on the plastic unnerved her.

At the water’s edge, she saw several mollusks. She exhaled. At least they had survived this bizarre flood of plastic. A speck of hot pink near one of the shells caught her eye. She bent down for a closer look just as a mussel shell opened a crack and released what appeared to be a tiny green pebble. It was plastic. The mussel must have mistaken it for food and then spat it back out.

About ten feet out, she saw a Snickers wrapper floating on the surface, before being yanked underwater. She watched as a sea lion carry the wrapper toward the shore in its mouth, pushed it onto the beach with its nose, and then slid back into the water.

Tania walked back toward the marina, trash crackling beneath her feet.

When she reached the parasailing stand, she told Ed, “Something crazy is happening. I just saw a shark shove a piece of trash onto the beach.”

“It’s happening all over,” he said. “This morning, I talked to my brother up in Oregon. All sorts of animals are doing it. Some of them push the trash and some of them puke it up.” He made a face as if he, too, were spitting something out. “Jesse saw an octopus carrying a plastic fork.”

“Dude! It’s horrible. What can we do?”

Ed shrugged and closed for the day.

The next morning, he texted her not to bother coming in. She waited until traffic died down and drove out to the beach anyway. TV vans and army trucks lined North Venice Blvd. Near them, she saw workers in hazmat suits.

Tania parked on a side street and headed for the sand. As she approached, all she could see was plastic. It was all dirty, wet, and tangled in seaweed, but none of it showed signs of decomposing. Tania slipped on a Ziploc bag and managed to catch herself with a quick sidestep. As she stood there, a sudden gust lifted an empty plastic bottle over the other trash and blew it into the water.

Without thinking, Tania stepped in and grabbed it, throwing it back onto the shore. Standing in the shallows, salt water soaking through her jeans, she looked at all the trash on the beach. The endless wrappers, bags, and bottles sparkled in the sunlight. Instead of disgust, Tania felt weirdly calm in the knowledge that the plastic was back where it belonged.

A wave approached, carrying a snack-size Doritos bag in her direction. She picked it up, shook it off, and shoved it into her back pocket. Next, she plucked a broken takeout container and a child-sized Croc from the incoming waves. She wasn’t the only human picking plastic from the water. A few others, alone or in groups, waded through the low waves, collecting what they could. She watched as a dark-haired man, in the water up to his chest, gently took a crushed two-liter bottle from the mouth of a dolphin and carried it back on shore. The interaction looked smooth and natural, as if the two were teammates or old friends. Tania stared in awe as the dolphin turned and swam back out to sea.

Then, she heard shouting. She looked inland and saw someone in a hazmat suit, yelling into a bullhorn, “Get out of the water!”

She didn’t have the energy to argue. She tromped across the layer of trash, making her way back to her car. As she passed through the parking lot, Tania saw two women in military fatigues setting up a fence of orange plastic webbing. A man nearby had an armful of “Beach Closed” signs.

She drove home, wet and exhausted.

Back in her apartment, Tania sat on the couch and clicked on the TV. She heard a news anchor say, “…seashores all over the world.” They showed video clips from Scotland. Malawi. Ecuador. Every shoreline was covered in trash. A NOAA scientist admitted she was baffled by the animals’ behavior, wondering, “How long have these species been able to collaborate?”

They cut to a beach in New Jersey that looked even worse than what Tania had seen in Venice. She turned off the TV and fell asleep on the couch.

A few hours later, she turned the TV back on and saw the CEO of one of the big bottled water companies, whose bright blue wave-shaped logo was easy to spot on the trash-filled beaches. The interviewer asked if he felt any responsibility for the environmental disaster. He deflected, “The problem isn’t plastic. Plastic only becomes a problem when individual consumers don’t recycle.”

When the interviewer mentioned a recent study showing that plastic recycling was a failure, the CEO cut the interview short.

Tania changed the channel and saw activists protesting in front of city hall in Downtown Los Angeles. Their signs said things like, “Save Our Seas” and “Ban Single-Use Plastic.” One person was wearing a whale costume.

The next day, the county supervisors held an emergency meeting. The beaches were a big tourism draw and the plastic trash was keeping people—and their money—away. The clean-up job was too big for the usual sand-combing machines, so they signed emergency contracts for backhoes and diggers and dump trucks. The trash removal crews worked around the clock, but they couldn’t keep up.

California joined other coastal states in requesting federal emergency aid.

Debates in Congress turned nasty. One senator suggested killing off all animals within a mile of the shore to stop them from dumping more of their trash. She stopped her rant when a colleague pointed out, “It’s not their trash. It’s our trash.”

Meanwhile, the plastic kept coming. The trucks carried load after load to landfills. Tania saw a video clip of a humpback whale nosing a broken kayak through San Francisco Bay.

More plastic, day after day. More trucks carting it all away.

Oceanfront communities around the United States—and all over the world—struggled to dispose of it all. Landfills in coastal states reached capacity, and landlocked areas refused to accept any of their neighbors’ waste.

On social media, a billionaire proposed a solution: blast the old plastic into space. In the comments, some people called him a genius. One comment pointed out that if aliens existed, they might do the same thing the sea animals were doing, with even more frightening results.

With parasailing excursions totally cancelled, Tania got a job doing data entry at an office in Sherman Oaks. The work was so dull that her thoughts often drifted to the ocean. She missed being out on the waves.

Eventually, the influx of plastic slowed. The oceans were cleaner than they’d been in years—but on land, people continued to argue about how to dispose of all the trash.

The billionaire who wanted to blast it all into space was back in the news. He’d paid a team of engineers to develop a space cannon he called the “Plastoblast.”

In early tests, the trash failed to break free of the earth’s orbit. Three compressed, 100,000-pound bundles of plastic were now circling the planet as unwanted satellites. The billionaire said they’d “make a few tweaks” and the upgraded cannons would blast the plastic “out of our solar system.” Even without evidence, people believed him. His company began shipping cannons to countries around the world.

A few weeks later, he announced a simultaneous global launch. People headed to the launch sites, eager to see the Plastoblast in action. After a thunderous liftoff, the trash bundles lost momentum. They failed to break through the outer atmosphere. Instead, they hurtled back to earth. The friction of their fall caused them to break apart and burst into flame.

Almost instantly, thousands of manmade meteors rained down on the unprotected planet, igniting wildfires and citywide conflagrations.

At home in her apartment, Tania watched the chaos on TV. She saw the Santa Monica Pier in flames. The Ferris Wheel tilted at a precarious angle.

The next day, Ed texted and asked her to come to work. “People want a birds-eye view of the wreckage.”

Numbly, Tania returned to her usual routine.

Over the next few weeks, she watched as sea creatures pushed the burnt plastic remains back onto shore.

The fed-up leaders of coastal states were unsure where to direct their anger. After a contentious conference call, they shipped the collected clumps of burnt plastic to Washington, D.C., on flatbed trucks, and dumped it all on the National Mall.

The impromptu monument was an eyesore and an embarrassment, and Congress responded. Ignoring the pleas of plastic-industry lobbyists, they banned all non-medical use of disposable plastic and required companies that had manufactured it previously to take responsibility for any future waste.

The plastic manufacturers sued, but public sentiment had turned against them. Nobody wanted to be seen carrying a plastic bag or drinking bottled water.

One morning, as Tania sat on the edge of her dock and listened to the seagulls overhead, something brushed her ankle. She saw a piece of burnt plastic floating next to her foot. She leaned forward and grabbed it.

A dolphin surfaced, facing her, with a scar over its left eye. Another dolphin, slightly smaller, popped up nearby. Tania felt a jolt of energy, as if something inside her had come back to life.

She reached down and splashed the water with her hand.

The bigger dolphin splashed back.