Beneath the Strange Surface: An Interview with Lysley Tenorio

Words By Dani Hedlund

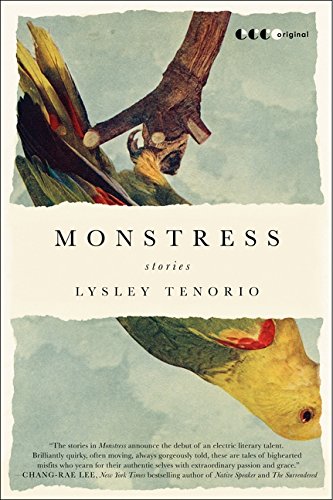

Literary works centered around the absurd have been gaining popularity, bringing us tales of the most outlandish characters and settings. However, as humorous and entertaining as a bizarre premise can be, the otherness often distances the reader from the characters, making it difficult to create a significant emotional impact. It is in this respect that Lysley Tenorio’s Monstress is unique. Bringing us stories of superheroes, leper colonies, and monster moviemakers, this exceptional short story collection shows us the humanity, and often the heartbreak, hidden behind these outlandish masks.

Monstress opens with the title story, inviting the reader into a fantasy world built out of toilet paper rolls, old tubing, and broken household appliances. From these meager supplies, monsters are constructed, space ships, squid children. “On film,” we are told, “everything looks real.” This is certainly true of the leading lady. In each film, she transforms into the grotesque monster her boyfriend envisions, her yearning to act in Hollywood romances hidden behind fake rubber boils and enormous wolf ears. However, as the two travel to America in hopes of saving their careers, the masks hiding their desires begin to slip. In a story as humorous and insightful as it is heartbreaking, we watch as the worlds of imagination and reality collide, leaving us yearning tragically for the illusion of film.

This unique story sets the pace for the following seven, each more outlandish than the last. However, just like in “Monstress,” behind the absurd situations, deeply authentic and moving characters dwell. From the secluded leper colony in “The View from Culion” to the fake-blood-spattered hotel rooms of “Felix Starro,” each story is united by a sense of bereavement. Often torn between lives in the Philippines and dreams in America, these lovable misfits struggle to find happiness in the most outlandish of situations. From superassassins to magical faith healers, from leper colonies to the VIP rooms in the Manila airport, Tenorio creates a sense of reality that few authors can access, one only made more potent by the strange world that surrounds them.

With sly wit and powerful prose, the reader of Monstress is not merely invited to watch as these stories unfold. Instead, Tenorio pulls us past the safety of the sidelines, holding us so close that we cannot help but experience the humanity simmering beneath the absurd. Certainly we laugh as three young men agree to mug the Beatles, as a boy describes his imaginary superpowers,kas drag queens assail a traditional Filipino household, but when we discover the desperation and longing behind their actions, the laughter opens into heartbreak. And at the close of each tale, their longing becomes our own, not only for the lives they dream of, but for the pages of their stories we have run out of.

Tenorio on Monstress

Tenorio was first inspired to write short stories when he took a class with Bharati Mukherjee: “I was just taking a lecture course on the short stories to fulfill a requirement.” When he found out Mukherjee had published several books of short stories, he decided to pick up a copy. The first book he bought was The Middleman and Other Stories, a collection that had won the National Book Critics Circle Award a few years before. “It just blew me away!” Tenorio explained. “Here was a woman, an Indian American author, writing about, for a lack of a better term, the American immigrant experience.” But what really impressed him about Mukherjee’s work was how she “stepped out of her own experiences,” writing not only from the perspective of an Indian American woman, but also from violent Vietnam veterans and Filipino aristocrats stuck in America. “That, to me, was so interesting.” After this inspiration, Tenorio began dabbling with writing, seeking to balance his Filipino American heritage with wondrous inventions of his imagination.

Although he said that his first years of writing produced some “really bad stuff,” he eventually found his rhythm by balancing characters straddling the Philipines and America with the outlandish circumstances that fascinated him. “It’s gotta be weird to keep me interested,” Tenorio explained, “but I understand that—or I’m paranoid that—my work could be read as too whimsical, too “lite”… And that’s the last thing I want.” This was one of the reasons he chose to steep so many of his stories with themes of heartbreak and bereavement, offsetting the strange and often humorous premises of his tales. Furthermore, Tenorio explained that since “conflict is the root of a good story,” he wanted to give those conflicts emotional depth. “I actually like the challenge of taking something seemingly unbelievable, unreasonable, or ludicrous and trying to give it enough emotional weight that the reader can take those situations and the people that populate that space seriously, as deluded as they might be.”

Although his stories are always connected by ethnicity, he relishes writing about characters he has very little in common with: “Working on these stories is just a way for me to bounce back and forth between situations that I neither have the courage or the foolishness to find myself in. I love it.” In particular, his characters vary greatly, jumping between gender, age, and outlook. When I asked Tenorio if he struggled to develop these colorful voices, he explained that finding the right way to tell the story—tone, idioms, pacing—is never his first concern. Instead, he focuses on finding a narrator who has “the right kind of dynamic with the other characters.” After he finds this character, the voice comes naturally. This isn’t to say that the right person immediately appears to Tenorio. He went on to explain that in the story “Brothers”—the tale of a cross-dresser who passes away after revealing his life-change to his family on TV—he originally wrote the older brother as an older sister. This version was constructed around having her breasts removed after she is diagnosed with cancer, only to have her younger brother artificially gain what she had lost. Tenorio threw his head back and laughed as he recounted that original version, how embarrassed he was now that he “actually let people read it.” Fortunately, he eventually discovered that he was focusing on the wrong conflict in the story, and he rewrote the sister as a regular guy, “living a plain, empty life,” grieving for his little brother and the man—or woman—he had been too ashamed to get to know.

Another problem that Tenorio faced when writing the stories that make up Monstress was length. “My stories tend to be longer,” he added, “and because of that, they were often hard to sell.” For example, when he submitted the title story, “Monstress,” to the Atlantic, they agreed to publish it only if Tenorio cut out a third of the story. “I wasn’t adamant that the story should stay that long—I was just happy someone would take it—but that was really hard,” he said. “I found myself, after that, really conscious about page length and compression, trying to get as much mileage as I could from one scene or one sentence.” Even now that he is embarking on his first novel, he hasn’t forgotten those hard lessons about compressing form. However, he is greatly enjoying the “breathing space” the novel allows him. For now, he’s decided to not worry about page limits—at least in the first draft. “I’m letting the scenes flow as long as they need to flow, indulging in dialoged and moments of reflection.” He knows that he’ll have to go back later and condense and revise, but for know, he says the experience is “liberating.”

Tenorio on Writing and Publishing

Although Tenorio had much to say about the difference between writing the novel and the short story, he said that the way he begins any work is the same: “I usually have a situation, and I try to lay out a very loose plot, almost like an outline. It sounds horribly formulaic, but it works.” Since Tenorio likes to focus on plot, this loose outline gives him a sense of destination. With the end always in sight, he allows the characters and situational aspects to fall into place naturally. These loose outlines also give him the motivation to keep working: “Even if the writing is going horribly, even if I don’t understand the character—and that’s always the last thing that I get—I have no excuse to not keep going. So if I know, at the end, they’ve gotta jump the Beatles, I have to find a dramatic and emotional and psychological way to get to that point.” Although he admits that often he does not get it right the first time—“or even the tenth time”—knowing where he is going helps him greatly aids his writing.

Furthermore, until he gets his characters to that point, he does not move on to other work. “I have to immerse myself in a story,” he explained, “and if I maintain my interest, even after that first draft, after that second draft, I keep going until I think it’s done.” He does not start another story until all the revisions are done and he’s sent it off to potential publishers. Then, as he waits to hear back, he embarks on a new project. “So, for the most part, I don’t go back and forth (between stories). Plus, it’s hard to shift the voices and I become so obsessed with one particular story because, even though it’s just a story, to me, it’s an entire universe.”

Just as he chooses not to switch back and forth between stories, he also does not daily switch in and out of “writing mode.” As a result, instead of trying to carve out a few hours a day to write—as the majority of our Tethered Tidings authors do—Tenorio waits until he has prolonged periods of time to write. Since he works fulltime, he writes a great deal during his summer and winter breaks. Also, in the past, he’s been honored with several fellowships and artist residences that taught him to write during these larger chunks of time. “I find myself very reliant on these long stretches of time that are almost meant to cater to creating. I wish I wasn’t so reliant on those things. I wish I could write in the midst of everyday routines, but I haven’t yet adapted.”

As our interview drew to a close, I asked Tenorio if he had any advice for our TBL writers. “Always be careful of the advice you receive,” he answered immediately, joking about how very seriously he used to take others’ advice, even when it was completely unhelpful. Secondly, he stressed the importance of finding a few very good readers to review our work. Tenorio says that if one or two of them are writers, that’s very helpful, but most importantly they should know what’s good and what’s not. “I tell my MFA students,” he added, “that one of the best things you can get out of the MFA program is a reader for life…I got that out of my MFA. I don’t send anything out until they’ve read it.” Lastly, Tenorio stressed the importance of reading, but surprisingly warned of reading too much. “I think sometimes,” he explained, “when you are having a bad writing day, and then you read something really amazing, that you get a little discouraged. Read enough to be inspired, but not so much that you become crippled by the greats that came before you.”

Excerpt from Monstress

In our battle against the Beatles, it was my Uncle Willie who threw the first punch, and for that, he said, he should have been knighted. I didn’t argue.

We fought them in 1966, the year they played Araneta Coliseum in Manila. They were scheduled to leave two days later, andrector of VIP Travel at Manila International Airport, it was Uncle Willie’s job to make sure the Beatles’ travel went smoothly, that no press or paparazzi detain them. But the morning after their concert, Imelda Marcos demanded one more show: a Royal Command Performance for the First Lady. When reporters asked the Beatles for their reply, they said, supposedly, “If the First Lady wants to see us, why doesn’t she come up to our room for a special exhibition?” Then they walked away, all the newspapers wrote, laughing.

Uncle Willie took it hard.

He called me that night. “It’s an emergency,” he said, “come quick!” He hung up before I could speak, so I snuck two San Miguel beers from the refrigerator and headed out. “I’m leaving,” I told my father, who was on the sofa with his feet on the coffee table, staring at the episode of Bonanza dubbed in Tagalog. He nodded and gave me an A-OK with his fingers. There was a bag of pork rinds on his lap and empty soda cans at his feet, and the whole room was littered with dirty plates and unwashed laundry. I even caught a glimpse of a bright pink bra that belonged to some woman he’d brought home earlier that week. We had lived like this ever since my mother left for what she called her “Vacation USA,” which was going on its fourth year, despite occasional postcards promising her return. Uncle Willie was the one who watched over me, but I was sixteen now, too old to be cared for. Still, if he needed me, I was there.

I met up with my cousins, JohnJohn and Googi—they’d been summoned too—and together we headed to Uncle Willie’s apartment. When we arrived, we found him at the kitchen table, fists clenched like he was ready for a fight, and he only grew angrier as he recounted the story. “Those Beatles insulted the essence of Filipina womanhood,” he said. “Special exhibition. Scoundrels!” I told him to calm down, that the Beatles were just making a joke, but Uncle Willie said nothing was funny about Imelda Marcos. He pointed to the framed black-and-white photograph of her on top of the TV, then brought it over and made us look. “She is the face of our country. Can you see?” In the picture, Imelda Marcos was seated in a high-backed wicker chair frilled with ribbons and flowers, staring out into the distance, her queenly face shaded beneath a parasol held by an anonymous hand. The photo was a famous publicity shot—you’d see it at the mall or in schools, even some churches—but I always imagined that it was Uncle Willie holding the parasol, protecting her from the scorching sun while he did his best to endure it. He wasn’t alone in his admiration for Imelda Marcos—the country still loved her back then—but Uncle Willie didn’t have much else. His last girlfriend left before I was born, and the demands of work, he said, allowed no time for another. Coordinating flights with Imelda Marcos’s schedule was the closest thing he had to romance, and instead of treating his devotion with admiration and respect, our family laughed it off as a joke.

I took the picture frame from his hands and set it face-down on the table. “Yeah,” I said. “I can see.”

“Okay,” he said, “good. Then the Beatles will pay for their insolence.”