As Nine stumbled with his words, a stifling heat rose beneath his cloak. Sweat beaded at the too-tight collar. He struggled to mirror the council-person’s rigid posture. She alone could invite him to stay at The Radiant Sun, offering them the home that would put an end to his days crossing the flood and a…

Excerpted and adapted from Deep Water: The World in the Ocean by James Bradley. Copyright © 2024 by James Bradley. Reprinted by permission of HarperOne (an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers), Scribe UK, and Penguin Random House Australia. On a gloomy winter afternoon, I step off the back of a boat moored near the outer edge…

Nico doesn’t know that Daddy’s dead, only that he’s been gone a lot longer than he should have been. Mama says maybe the boat found more scallops than there normally are this early in the season, and maybe he decided to see how many he could catch in one go. But Daddy’s never fished more than two weeks at a time, and tomorrow morning makes three since he left. I know he’s gone for good this time, but I don’t say this to my brother.

Nico runs down the beach in nothing but his swim trunks, wire bucket in his hand. It’s October and the water’s barely warm enough for swimming, but Mama asked me to get some quahogs today since the weather’s so nice. They bury down deep in the sand, and you have to get out past your waist to find the big-bellied ones, but I hate the feeling of eelgrass on my feet, so I told Nico he had to do it. I say it’s a game and that if he fills the peck basket in under an hour then I’ll make us hot dogs for dinner. They’re his favorite.

Mama’s been working overnight shifts at the diner this week, on account of Daddy’s trip being prolonged. That’s what she calls it, prolonged. She says it’s running longer than it should but it’ll be over soon, that he can’t call to say goodnight since he’s working hard to find fish like most of the other dads on our island. Thing is, most of those dads have already come in and gone back, unloading their catch and spending a night at home like our own father was supposed to. I know Mama’s worried ’cause she’s been talking in her sleep again. Real words but also sounds like she’s crying and doesn’t want anyone to hear. I stay quiet when I do, until the house is still and the only sound is my brother breathing in the bed next to mine. He sleeps through everything, which makes it easy to protect him.

“I found three, Mari!” Nico yells from the water. Daddy always goes quahogging when he’s home, so I think he’d be okay with me making Nico do it now. I give him two thumbs up and watch the horizon, looking for boats coming back from the edge of the world. I stay still and wait for something to change, but the wind is steady from the southwest and I get itchy from the spray. I decide to walk down toward the end of North Cove, knowing Nico will be fine without me for a few minutes.

The beach is lined with new houses, the kind owned by people who live in Boston and only come for a few weeks in the summer.

Skukes, we call them behind their backs. Each June they come down in droves and pluck shells and sea glass from the surf, burn midnight bonfires. They shop at the outlet mall; they don’t go to church on Sundays. I remember when I was little and there were only a few of these houses lining the shore, and now there’s so many that they look like a wall—long and high. I’ve made friends with a few of the kids, but they’ve never asked me up to see the inside. They make me feel like I don’t belong when really it’s the other way around. Mama says the houses are up on posts so that the hurricanes don’t wash them away; Daddy says it’s because the people that own them think they’re above us; I think they’re both right.

The wind’s picking up and I untie Mama’s pink sweatshirt from around my waist as I turn back. It’s the one Daddy bought her when we went to Cuttyhunk last spring. It smells like her perfume, all powdery and clean, and I lift the edge of one sleeve to my nose so I can find her better. Mama says that even when you don’t have nice things, you should still try to make it look like you do. That’s why she always wears perfume, even when it’s Saturday and she’s gutting bluefish for dinner. I breathe her in and walk back. Nico’s tugging the basket behind him as he comes up the beach and I see it’s already full. He’s beaming sunshine from the round spots on his cheeks. “Make my hotdog with relish, Mari,” he shivers, and I smile because Daddy always asks Mama to do that for him. I throw a towel over him and he laughs light and quick, the quickest glimpse of our father.

“It’s really okay that we’re eating meat on a Friday?” he asks.

“I don’t think Jesus’ll mind.”

“Mama would.”

“She said it was fine,” I lie. “C’mon, storm’s coming.”

Nico runs ahead of me and beats his bare chest, yelling like he’s king of the beach. I carry the peck basket and sort through the batch; I didn’t check it before we left, and we’ll have to throw some back since they’re too small. I toss a handful out into the surf and remember Daddy saying you have to be honest when you fish so that there’s always something for everyone. I want to believe he’s still out there even more than I want Mama to tell Nico the truth that he’s not.

“Mari!” he yells, his voice stolen by the wind. He’s kneeling in the sand next to a brown cardboard box and waving at me to come toward him. We can never come to the beach without him finding something to take home, and I hope that this time whatever’s in the box isn’t garbage. People throw things out of their cars when they’re driving over the causeway, things they don’t want or don’t want others to find, and the ocean takes them away. Tires, empty gas cans, old soda cans—you name it, it’s there. One time I found a needle like the ones the doctor uses to give us shots, and Mama said no more picking things up unless she was with us.

I touch my brother’s shoulder and look inside the box.

“Bunnies,” he says, and I count their small bodies. Twelve in all, huffing and heaving against each other as if they might blow down the box and scatter. “Where’d they come from?”

I want to tell him that someone didn’t want them, that they’re too small and birds will eat them since they don’t have their own mama to protect them, not like we do. “I don’t know,” I tell him, just because it’s easier and he won’t fight it.

Nico picks one up and holds it near his face. The rabbit stays still with its eyes shut, but I can see it tremble. Nico makes his own eyes big and looks me square. “Can we keep it?”

I know we can’t, that there’s hardly enough food for us as it is. It’s why Mama sent us out clamming today.

“What would it eat?” I ask.

“Milk,” he says. “And grass and lettuce when he’s bigger.”

“And then what? Where’s it gonna sleep? What’s it gonna do when you go to school? Prince will eat it in one bite, first chance he gets.”

“No, he won’t!” Nico cries, hugging the rabbit into the hollow of his neck. Its ears stick out and wiggle in the air. There’s goosebumps on my brother’s arms and now he keeps his eyes closed tight. Mama would say no; Daddy would say maybe.

I shiver and grasp the sleeve of Mama’s sweatshirt, then take it off and wrap it around his shoulders.

“Put it inside,” I tell him. “In the front pocket, so it doesn’t get squished when you walk.”

“What about the others?”

“What about them, Nico?” I do my best to hold a stiff face like Mama does when I bring home bad grades. Nico pouts his bottom lip but doesn’t say anything, and we walk on.

We’ve lived on West Island since before I was born, in the house where my Daddy was once little. It’s got a porch in front and an orange buoy swing in the backyard, near the vegetable patch where we bury our old dogs. We raise Newfoundlands and Mama names each one Prince, so that when one’s gone we always have another. Prince the Fourth is our dog now and he’s waiting under the porch with his tail wagging.

“You stay away from that dog or we’ll have rabbit soup for dinner,” I tell Nico and hand the peck basket to him. I don’t think Prince will actually eat the rabbit, but I don’t want Nico to know that. “And put the quahogs in the sink so Mama can clean them tomorrow. Do you want carrots or potatoes with dinner?”

“Both.”

“One.”

“C’mon, Mari!” he whines.

I wait. He knows Mama’s rule: only one vegetable at a time so the others can keep growing.

“Carrots,” he says, and stomps up the stairs so hard he startles Prince out from his hiding spot. I pat him on his head, and he crawls back under the porch, waiting in the dark for his dinner.

Inside I hear Nico in his room talking to the rabbit, and I’m grateful he’s not whining at me to sneak some cartoons. Mama has a lot of rules, and it’s my job to make sure we mostly follow them when she’s not here. No TV, unless it’s the weekend. I’m the only one allowed to use the stove since Nico tried to make grilled cheese once and scorched the wallpaper when he forgot to flip the bread. We have to do our homework before we can play outside, there’s no whining about going to church, and we have to rinse our feet off at night when we’ve been at the beach so the sheets don’t get sandy. Since Daddy’s been gone there’s been a whole bunch more rules, like no answering the phone and no TV or radio when Mama’s not there. I know that’s because they’re talking about the boat, about Daddy and the crew and how no one knows where they are.

Mama’s even been hiding the newspapers, but I found one yesterday under the porch and it said they’re gonna call off the search soon if nothing changes.

I make Nico copper pennies with maple syrup and save the carrot peelings for Prince; I’ll let him come inside after we eat, even though Daddy says the dog makes the house smell like feet and Mama gets mad when Prince’s hair sticks to the old green couch. I put water on to boil and turn to the clams, which sit in the sink like a pile of rocks. You have to fill the sink with cold water and leave them in there for a long time so they spit out all the sand and dirt, or else when you eat ’em later you’ll taste grit. I think about how long it takes for them to get clean and wonder if that’s what Daddy’s doing down in the water, spitting out the stuff that doesn’t belong before he goes up to Heaven.

“Mari, the pot’s boiling.”

Nico’s wearing pajamas with ducks on the front. He’s holding the baby bunny, who’s wrapped in a towel. Its eyes are open now and they’re shiny like marbles, two little orbs taking in this strange new world.

“I know,” I say and turn the knob down. “How many hot dogs do you want?”

“Can I have two?”

“You can have three.”

“Really?”

“Yes, I’m still full from lunch. You need to feed your rabbit first, though.”

Nico scurries to the pantry and pulls down a nearly empty box of powdered milk, the one Mama wrapped in a plastic bag so no bugs get inside and have babies. But I know there’s bugs in there, and don’t rabbits eat them anyway? “Let’s finish the box,” I tell my brother, “and we’ll get a new one at the store tomorrow before Mama comes home.” Nico nods and pours the powder into a cup. I spoon hot water on top and mix it, and soon we’re dipping our fingers and the rabbit’s sucking down droplets from our pinkies.

“She likes it,” Nico smiles.

“I thought you said it was a he.”

“It’s a she. Amelia.”

“You named it?”

“So?”

I place the hot dogs into the simmering pot. I know this means we can’t get rid of the rabbit now; it’s why we never name the chickens, so it’s not sad when we chop off their heads. Amelia licks Nico’s pinky and I hand him the cup of warm milk and tell him he needs to find a shoe box for her to sleep in. They go off in search of her new home, and I dish up supper for Prince. I chop the ends off the hot dogs since Nico won’t notice them gone, and scatter them around the slurry with the carrot peelings on top. I make Nico’s hot dogs with relish and put the copper pennies in a bowl, then yell to him that I’m gonna feed Prince and he should eat while it’s hot.

On the front steps, it’s nearly dark now and Prince gobbles his food down like he hasn’t eaten in weeks, when really it’s just been since last night and he’s gone longer in the past. I wrap my arms around him tight and listen to him breathe, calm and steady. This Prince is mine, and the next one will be Nico’s. I like how everything about this dog is dark except his tongue, how it sticks out like a little splash of pink paint that someone forgot to wipe up.

We sit on the steps until rain starts to fall and I stand and push Prince up to wait by the door. I like the way our house looks, lit up yellow from the inside with the black night around it. It’s always warm and safe, my favorite place in the whole world. Daddy was going to put a new roof on this year, “before the first snow,” he said. But now he’s not here and the shingles are peeling up in the wind, and I wonder how long it’ll take before we’re stepping around pots and pans in the living room to catch the rain leaking in.

Prince barks and the darkness comes back, and I let the light pull me inside. He shakes his back and sends water everywhere so the air smells like dirt and salt and musty fish, then he runs into the bedroom I share with Nico. I step softly down the hall so they won’t hear me, and I peek around the doorframe.

Nico is belly-down on the floor wearing his shiny Easter shoes, the box they came in now full of dish towels and brown fur. Prince looks up at me and I hold up my hand, telling him to stay where he is and willing him not to jump down and scare the rabbit. The last thing I need is to have a wild animal loose in the house.

In the kitchen, I drain the sink and move the quahogs; their water needs to be changed anyway. They sit on the counter with their feet poking out while I wash the dishes. It doesn’t make me feel better, not like I wish. I wish I could go to church now. I miss the candles and the incense, the way the light falls through the stained saint windows and lands on the choir while they sing “One Bread, One Body.” I want to kneel in the confessional booth and feel better like I do when I tell Father Murphy about sneaking candy after dinner or giving April Perry the middle finger on the bus. I want to tell him I’m lying for Mama, for Nico. Instead, I put the quahogs back in the sink with new water, turn out the light, and return to our room.

The light’s still on but Nico’s asleep on the floor, the shoebox cradled against his stomach. I take the blanket from his bed and tuck it around him like when we sleep on Daddy’s boat. He sighs and puckers his lips, same as he did when he was a baby. Amelia shuffles in her towels and looks at me through one eye. She is so calm, not like I thought a wild rabbit would be, so I put the lid on but leave it ajar. Prince digs on the carpet and I hear him turning ’round before he settles in to sleep next to my brother. We are all together in this room, safe and sound and home again. Outside, the rain hits the windows and the wind blows hard, and I fall asleep thinking about spring.

I wake to a thin light poking through the curtains, same as it does every morning. It’s chilly now, much more than yesterday, and the tip of my nose is numb. Prince thumps his tail and stares at me from the floor, where Nico’s spread out like a starfish with the covers kicked off. I get out of bed and cover him again, then I peek inside Amelia’s box. She is there, quiet as I left her, with that one eye still looking at me. Her nose twitches and makes me want to sneeze, and I put the lid back on. I feel warm like I do when Mama catches me in a lie. Mama will be angry when she sees, and I know I’ve made a mistake. I still need to get to the store before Mama comes home, so I bring the box to the kitchen and take a few dollars from my allowance jar and leave Nico a note that says I’ll be back in time to make waffles and please not to make them himself. Prince follows me to the front door. I grab Mama’s pink sweatshirt and put it on over my pajamas. I do not want to leave, but I know I have to.

Outside the morning is sharp and the puddles splash against my bare feet. I walk quickly toward the causeway, knowing I have to get rid of this rabbit. Mama never would have said yes in the first place, no matter how much Nico cried. She’s hard and soft at the same time, and I decide that I’ll get a candy bar at the store as a peace offering for Nico.

Prince stays at my side as we keep going toward the beach, toward the place where the sun sits low on the edge of the ocean. I wish it would go back down there and pull my Daddy up with it. I know that he’s down with the stones and sharks, looking up through the water like he’s looking at the sky. The sky above my head rolls thick with clouds crashing into each other, all gray and silver and blue. Prince runs toward the jetty and barks at cormorants that’ve taken over the osprey’s nest inside the channel marker. That’s how you know summer’s really over: the osprey stops crying and takes her babies south before the devil birds move in.

I pull Amelia out from Mama’s sweatshirt and hold her tight between my hands. I don’t want to love her, but I do. Especially the way the smallest bit of sunshine goes through the thin pink skin of her ears, like light coming through stained glass. I didn’t know I could love something so quickly, and I hope it will be just as easy to unlove her, to not hurt or wonder about what will happen to her. Her old box is up ahead, a few yards from where Nico left it, and I push away the thought of him waking up to find his rabbit gone. Amelia twitches and I kneel down to put her back where she came from, back where she belongs, so that she can be a worry for someone else instead of us.

Inside the box the other rabbits are still. They’re covered with wet sand and stray pieces of seaweed, and they don’t look up at me like they did yesterday. I touch one: it’s cold and limp and its chest stays still when I press on it with my thumb. Water comes out of its mouth. It doesn’t cough or tremble. It doesn’t do anything. The others are the same. I put Amelia in the front pocket of Mama’s sweatshirt and feel her move, clawing around with the dollar bills and settling. We stay still together while I decide what to do.

I do not know how to take care of this thing that needs so much taking care of. If I bring her back to our house and place her in the garden, a hawk will make quick work of her. If I leave her on the beach, she will be blown away with the gale. I can’t get to the animal shelter on foot either.

Prince lies down in the dune grass and whines as I drag the box down to the surf. I let the water wash over my knees, feel the sting on my cuts and scrapes, and imagine myself being made clean. I do not want anyone to find these dead rabbits—especially my brother—and the sea will swallow them like it swallowed up my Daddy. That’s what it does best: we sail its waters, we steal its fish, we pick its quahogs. But for everything we take from it, it takes from us tenfold. High tide is coming, and the current will pull the box out to the open sea and the other islands. It will sink somewhere in the between.

I pull Amelia from my pocket and she stirs, as if this were all a dream and she was deciding if she should wake up or roll over. I blink tears and one falls on her head. She barely even moves. There is no chance of hope for her here, so I place her inside the box with her brothers and sisters as though she were a Sunday offering and watch as she hunkers down between them. She fits there, and I close the top before pushing the box into the water.

I try to be gentle and let the water take her like Moses in the reeds. The box moves slowly at first, then all too quickly until suddenly it’s out of my reach before I can grab it back. I know Mama is lying to us about Daddy because it’s her job, because it’s what she has to do as our mother. The box sinks lower and joins the horizon, the same as my Daddy did when he went off on his last trip and we didn’t know he wasn’t coming back. Now Mama and I both have secrets to keep from Nico.

I stand in the water and the eelgrass licks my toes, and I think about my brother asleep at home, how soon he’ll wake up when the gray light turns gold and realizes his rabbit’s gone. He will scream and howl, and it will be my fault. He will forgive me, I tell myself. Someday. I try to think of happy things as I call out to Prince and trudge toward the road. I lift the sleeve of Mama’s sweatshirt to my nose. I think about her and the neon lights of the diner, the way they catch on her teeth as she smiles when she sees us coming in the front door, how they make the darkness under her eyes look deep like still water.

Mama’s the kind of person who pushes her shopping cart all the way back to the grocery store when we go shopping. She gives money to the Boy Scouts when they fundraise outside the library. When I get mad and yell at her, she yells back but always tells me she loves me. When we fight, she makes me go to my room and then brings me warm milk. We kiss and make up. She puts notes in my lunchbox, goes to all of Nico’s football games, and lets Prince lick the bottom of the peanut butter jar. She always kisses Daddy no matter how awful he smells. Always. My mother is good, right down to her core, even when she doesn’t seem like it, and I hope one day I’ll be good like her too.

It’s not that we didn’t know. Your name, after all,

was the Ghost Ship, some kind of omen for what you’d become.

Ferrying somebody’s sister, somebody’s body, some bodies

across that fiery water: elsewhere. I don’t believe

in elsewhere, an eternity of fire or sun. You were mannequin arms

and a rug on a dance floor. Some kind of baroque, you

were built of pallets and tar paper, old couches, and terrycloth.

Everything that burns. You were art, and art is always worth burning.

I don’t believe in fate. I believe in grief, what it does to us.

Somewhere, somebody said: intergenerational trauma.

This isn’t my grief, not mine to carry, a chalky

fire-crisped piano, the twanging sound of each string popped

by heat. Everything can be a performance. The hand-

lebars of a ’65 Panhead. Your dark mustache

and aviator shades. You didn’t die in this fire’s crush:

a dream filled with opulence and hope.

Rents so high twenty-two people live and build

where they build beauty, too. This wasn’t how we lost you—

timbers crashed in char and singe, staircase crumbled

in smoky crush—

The things we love to blame, the things we love

end us. One fire or another, inheritance

of doors burned shut. I think of you with no escape

I think of you how could I not

my first ghost I wish I could

sail back to you I wish I could remember

[The italicized line “a dream filled with opulence and hope” is taken from Ghost Ship

founder and master tenant Derick Ion Almena’s Facebook post the day after the fire.]

They say it comes in waves, grief, like the swell’s crush against your small board in the ocean, you learning to surf on such a vast sea, learning like the boy so proud at the front of the class Coach quizzing him, the boy pointing at his own body, moving tibialis, gastrocnemius, latissimus dorsi, the whole body hurts, doesn’t it, after a day of surfing muscles you didn’t know you had muscles writing the next day, sore, the neck turning to watch for coming swells, for what you know will come, what you wait for, can’t avoid, pointing here, here, trapezius, pectoral, the pull of your body and the hard board pushing back out against the waves coming and coming barely any relief in between.

She builds a causeway of her own skin : a road to the sea

She is all water hard-shelled crab, heart of fish, hidden sting

of extinct scorpion

Her bruised nape, sore hip, skewed scapula the intoxicating smell

of white flower oil and human touch

She is looking for a way back to herself : people, flesh, bone, spirit

Can she call their names with her seaweed mouth?

She floats between meditation and sleep, body hovering like a frond blown onto calm seas

She is mathematics and perfect form : parabolic sand dune, eyelashes of grass,

fingernails the empty shells of mollusks

Can I lie in the sun on the shore of myself?

She built this landscape of what she loves

salt-licked and kelp-strewn : let me rest

Let the swell of the tide carry my love her loss out to the deep

Of course, Lâm got the nighttime shift again. The one shift she thoroughly hated. Neither her coworkers nor her supervisor understood why. Surely it was the quietest time, with the fewest arrivals of Descendants, the least paperwork and processing?

Of course, Lâm had never started on the Path herself. Her Call was old and kept pulling at her, but unlike the Descendants, she had never heeded it. This created a situation that Lâm had not seen with any of the Descendants she met at work: her Call seemed to be completely invisible. At best, her coworkers thought she hated night shifts because of Minh, who was usually running security at that time and whose relationship with Lâm could best be described as tense.

But it wasn’t about Minh (who was, truth to tell, a rigid and sanctimonious idiot).

The trouble was that there was nothing to do at nighttime. Once Lâm was done with rearranging the layout of the reception desk, with cleaning the teaware five times, and making sure everything was in its proper place for the breakfast buffet (it nearly always was, because the evening team had done their jobs), once she was done with all these avoidance tasks, with all the minutiae of small things she could do to stave it off, once she was sitting at reception, staring at the screensaver on the computer, at the slow dance of the Path Company’s logo moving like algae waving in some invisible current…

…Once she was done, the visions of the Call always came.

It always started small: something on the edge of her field of vision, a shimmering, a faint wavering of the paintings in the reception lobby. The backs of her hands itching. A barely perceptible smell of brine, and the sound of the wind slowly and steadily rising, covering the noise of the computer’s fan, the motor of the vending machine, her own frantic heartbeat.

Slow and steady, and never stopping.

Then the odd, uncomfortable feeling of her skin tightening, too small to hold in the whole of her unfurling self—a desperate need to scratch it all off, to finally breathe, in all her power and glory.

By that time, the whole of the reception lobby was usually overlaid with a faint pattern of waves, and Lâm would hear the crash of the ocean in her ears. And then she’d look down and see her hands—the shimmering imprint of scales beneath her skin, the lengthened fingers ending in claws. And it would feel so easy, so tempting to just go towards the waiting Path, to travel its length to its end at the nearest harbor.

Someone was screaming. Something touched her shoulder and it was viscous algae, and she jerked away, and she—

“Excuse me?”

It wasn’t algae. And the person wasn’t screaming, but talking. It was a guest.

Lâm looked up, blinking to clear away the undersea landscape. A hazy silhouette stubbornly refused to come into focus. Her eyes had adapted to undersea sight and didn’t want to return to normal. This had happened before. She was going to be all right, once it cleared. She was going to be all right. All she had to do was her job.

“Yes?” she said. Her voice felt faraway, booming and too large for the lobby. It was unfair, grossly unfair. She hadn’t asked for any of this.

She had found over the last three years that working in a Descendant hotel made resisting the Call easier for some reason. It wasn’t her favorite job: when she worked the night shift, it meant she couldn’t join her housemates for dinner. Nga would make sure she had food left in the fridge—she really behaved like a full-on auntie, mothering Lâm even though she was a year younger. And after night shifts, Lâm usually arrived back home before Công left for her office job, which meant they could catch up over a shared meal—Lâm’s late dinner and Công’s breakfast—discussing the latest books they’d read and the incongruous things they’d both seen on their way through the city, which Công so loved to sketch.

“I’m really sorry, nothing else was working to get your attention.” The voice was female, older than her. “I really do need the room.”

Reflex kicked in. A late arrival. Despite the apology, the guest didn’t sound sorry. There was a faint iridescence to her skin and eyes, which meant she was already some way along the Path and used to the way the Company eased her passage as she slowly made the journey toward the nearest harbor, toward the sea that would become her home.

Lâm tried hard, very hard, not to think of her mother’s own Path, of the tautness in her emaciated face toward the end, of the sheer relief when she and twelve-year-old Lâm had finally reached the harbor after weeks of travel.

Of the way the sea had risen to meet her mother as she waded in—a whirling of ribbons of water spreading out from her and the shadows of dragons gathered in the open sea, calling her onward.

Mother hadn’t looked back or expressed regret. Not once. The Call had erased all that from her—even the desire for land food or drink. Even love for her own child. No, she hadn’t looked back, and Lâm had been left behind, trying to move on. But how did one move on from that?

Nga, drunk at night, often got blasphemous and said that Mother had failed parenthood, and she didn’t deserve to be worshipped or remembered. Lâm would shake her head and say it wasn’t that easy and the argument would end over a plate of mung bean cakes with nothing solved—neither Nga’s bitterness at the way parents sometimes behaved nor Lâm’s resentment and loss. Công simply shook her head and said that sometimes people were weird, and that didn’t help either.

Lâm hadn’t told either of them about her own Call. It was too hard, too personal, too fraught. She didn’t want their friendship to sour or end, the way it was bound to if they had that conversation. Descendants weren’t meant to have attachments or friends once the Call came; everyone knew that Descendants would be inexorably drawn into the sea.

Descendants. Con Rồng. Children of the Dragon. Called to the sea. Blessed, the Company said. Except that, of course, it was everyone else who picked up the pieces and everyone else who had to deal with the consequences of such barbed blessings.

“I’ll need you to fill this in,” Lâm said, sliding a sheet of paper in front of the guest. “And ID and a card, please.”

The guest frowned. She looked a bit like an older Công, all harshness and sharp observations. “A card?”

“A credit card. For incidentals.” Lâm made her most practiced apologetic face. “The Company covers meals and accommodation on your journey, but you may want extra things. Mini bar. Room service.”

The guest studied the registration form as if it had personally offended her. Lâm studied the ID on the desk. Nguyễn Thị Nguyệt Uyển, a traditional and old-fashioned name. Place of birth was in the western provinces, a long way from Azure Sky Hotel. She was near the end of her Path. But asking about her Path would be too personal, too intimate, and Lâm didn’t want that sharp gaze turned on her. So instead, she slid the card and the ID back and proceeded with the registration.

“Here you go,” she said. “Your room number is written on the leaflet and the lifts are this way. Breakfast is at 10 a.m. and here are your access codes for the Path app. It interfaces with the guidance system on your phone’s maps, so you’ll know where to go next.” Not that she’d need it—as Lâm herself was ample proof, the Call was relentless, as unerring in its accuracy as the instinct of migratory birds. Descendants never got lost. They went where they were supposed to, all of them.

All except middle-aged, stubborn, selfish, scared Lâm.

Lâm expected not to see Nguyệt Uyển again. Her shift ended early in the morning, before the breakfast room was opened. And she was exhausted. Lately, night shifts left her feeling that way, like she’d run a marathon and never stopped. She’d come home and collapse, barely able to talk to Công or enjoy Nga’s food.

But when she emerged from yet another bout of visions and hallucinations and went to the tea rooms to boil water for a grounding drink, she saw that Nguyệt Uyển was sitting cross-legged in front of the table furthest from the kitchens. She’d gotten herself one of the complimentary tea sets, and she was staring at the delicate blue porcelain cup in front of her. Lâm couldn’t see her expression. From the back, she looked so much like Mother that Lâm felt a stab in her chest, an icy twist around her heart.

Don’t do it, Nga would have said. It’s not worth it.

She’s not Mother, Công would have pointed out. But Lâm was neither of them.

Before she knew what she was doing, she was walking toward the table. It was highly improper to bother a guest, but what propelled her was even harder to resist. “Are you all right?” she asked. “You should get some sleep. It’s a long journey.”

Nguyệt Uyển looked up, her distant gaze returning to focus on Lâm. The faint scattering of scales on her cheeks disappeared. “That’s very kind of you—” she stopped, leaving an all- too-obvious space.

“I’m Lâm.”

“Would you care to join me?” Nguyệt Uyển gestured towards the tea.

Lâm hesitated. She wanted to go home. She wanted to sit with Công at breakfast and discuss Nguyệt Uyển the way they discussed that odd man on the bus, or the child disguised as an ornate lion dancer near the noodle shop. Odd, amusing, the subject of distraction and laughter. Distant. Safe.

“It’s late at night,” Nguyệt Uyển said, “and it’s not like there’s much to do. Or would you rather remain alone with your Call?”

Lâm had not expected that. Not—not that. No one was supposed to see her Call. “How—how do you know?”

A smile from Nguyệt Uyển. “It’s my job. Or used to be.” There was an odd inflection in her voice: half-regret, half-anger. “Marine theologist. I studied dragons and Descendants.” She snorted, genteel and careful. “Somewhat ironic that I’d end up being Called. But anyway, it’s hard to miss the look of the Called. You’ve got it and you’ve got it bad.”

It was all too much, all too casual, all too probing. Lâm sat down, overwhelmed, watching Nguyệt Uyển pouring tea in a practiced gesture. The smell of jasmine and cut grass wafted up to Lâm. “You don’t sound very concerned about being Called.”

“Concerned?” Nguyệt Uyển stared at her tea. “I suppose I’m not.”

It was Mother all over again, wasn’t it? A wound that could never close no matter how much therapy Lâm tried on it. And yet… perversely, she found herself envying Nguyệt Uyển’s serenity. She seemed utterly unperturbed by the effects of the Call. “Have you no family?”

“I do. My husband was Called a few years back, and our daughters are grown now. You?”

“No,” Lâm said. She’d had a few girlfriends, but the Call made it hard. By daylight, it was sort of manageable, but few relationships could endure night after night of nightmares that would leave her gasping and struggling to distinguish between vision and reality. But she had Nga and Công, her little community of people where she belonged. Those who looked after her as she looked after them. “It’s all right, really. I’m not lonely.”

A sharp look, but Nguyệt Uyển said nothing. Instead, she poured them both more tea. “I made my goodbyes to my daughters, but it’s not like I’m going very far.”

“Dragons don’t come back.” Lâm’s voice was harsher than she meant it to be.

“Hmm.” Nguyệt Uyển sipped at her tea. “That’s not quite true and you know it. Get a boat and go out to sea, and they’ll come.”

She’d tried that once, when she was twenty. A small boat hired with Nga and Công, the movement making her seasick; the wind buffeting her as she stood on the deck, the smell of the sea everywhere, swallowing up Nga’s angry words and Công’s observations. Then, silence. And dragons. Dark silhouettes seen underwater and then by the side of the boat, staring up at them as the wind died down.

“Yeah,” Lâm said. “They do. But they’re not the same.” They’d all looked alike, and whatever language they spoke had made no sense to Lâm. One of them had come closer, staring at her, antlers shining with sea salt, droplets of water scattered in their iridescent mane. She’d called Mother’s name but they hadn’t answered, just remained there staring at her with the open sea between them. But then the other dragons had called out, and they’d turned and dived back into the water, blessing delivered, storm quelled, nothing more.

Nguyệt Uyển’s gaze was sharp and compassionate. She didn’t ask who Lâm had lost. Instead she said, “The Call runs in families. Not always, but often. So it wasn’t exactly a surprise for me.”

Lâm said, before she could stop herself, “Is that what happens, when you walk the Path? You just… stop caring?”

“About what?”

“Everything. People. The family you leave behind. The things of the world. Just—” The pleasant warmth of the sun on cobblestones; the small terraces with tea and dumplings, Nga’s and Công’s laughter wafting in the evening breeze; the sharp, acrid taste of the first tea in the morning, looking at sketches alongside Công.

A silence. Nguyệt Uyển was breathing in the tea, slowly, deliberately. “Everything you lose…” she said. “Drink your tea,” she added, not unkindly. “I’d like to ask you a question. You don’t have to answer. Though I’m older than you and a guest, and I measure the respect and obeisance you think you owe me, I’m not here to pry. At least not unduly. How long ago did they leave you for the sea?”

Lâm was silent for a while. She’d not told anyone on the staff. But there was no one else she could talk to in this way, and it felt like a burden she’d borne for too long. “I was twelve,” she said. She stared at her hands, half- expecting to find the imprint of scales on them again. “I don’t know how I’m meant to deal with that.”

“The same way we deal with everything,” Nguyệt Uyển said. “The best that we can with what we currently have.” She sighed. “You say I’m not concerned. I am. I’m angry that I have to leave everything behind. I’m sad that I won’t get to see either of my daughters marry or have children or be there for the rest of their lives. I’m scared of what it’s really like, to be in the sea. And I have regrets. Of course I do. But it’s not like I have much of a choice.”

“And so you just… give in?”

A shrug. “I’ve learned to accept it. It’s what the Path is, isn’t it? Why the Company exists. Not for accommodation and meals, though I guess that’s part of it. But with each stop—” Another shrug, a touch of rainbow light in her eyes, reminiscent of the dragon’s gaze on Lâm all those years ago. She could hear the roaring of the wind in her ears. “With each stop, one gradually yields to the inevitable. As I said, I’ve made my goodbyes.”

“I refuse.” The words were out of Lâm’s mouth before she could stop them. There was too much bitterness bound up in all this. “I have people here. I won’t leave them.”

“That’s good, I guess.” Nguyệt Uyển didn’t sound convinced.

“Are you mocking me?”

“I’m not.” Lâm saw that there was pity in her eyes and that felt even worse. “You said you were all right. I’m glad you are.” She set her cup back on the table and looked up, behind Lâm. “I think your colleague is looking for you.”

Lâm turned. Minh was there, his face flushed—by his expression, something had gone wrong, and he needed Lâm’s softer touch to untangle whatever messy situation a guest had come up with. “You’re right,” Lâm said. “I have to go. Thank you for the tea. And you really should get some sleep.”

Nguyệt Uyển inclined her head. Her gaze was distant once more. “May we meet again,” she said.

May we not, Lâm thought, but she was rattled enough that she couldn’t get the words out of her mouth.

Lâm finished her shift with no further incidents. She rode the bus all the way back to her flat more exhausted than she’d ever been, the visions of the Call superimposing the darkness of the depths atop the shops and the streets.

At home, Công was waiting for her. “Hey,” she said. “There’s shrimp soup in the oven. Nga left it to warm before she went to work.” She was sipping a bowl of congee with salted eggs. “How was your night?”

Lâm found herself at a loss for words. Behind Công, she could see algae clinging to the kitchen cupboards and the sound of the wind was almost drowning out what Công was saying. “Not bad,” she said, automatically. “How was your day?”

“Interesting,” Công said. “I found a little temple on the Fifth Avenue, near the Azure Gardens. Had no idea it was there. Look.” She opened her sketchbook. All Lâm saw was waves and dark shapes, and instead of Công’s enthusiastic descriptions of worshippers, all she heard was the whistling sound of the wind and the thunder of the distant sea.

“I’m sorry,” she said finally. “I’m exhausted. Can we talk later? When I’ve had sleep.”

Công’s face darkened. She opened her mouth, said something—and when Lâm didn’t react, reached out to touch her shoulder. The visions died away. “They work you too hard. You know that? You’ve barely gone out in months. You always say you’re tired. Can’t you just say no to them?”

“Please.”

“All right,” Công said. She swallowed the last of her congee and closed her sketchbook. “I’m off to work. I’ll see you tonight?”

“Of course,” Lâm said, and it felt bitter on her tongue, as if she was lying.

After Công had left, Lâm retrieved the soup from the oven but found she wasn’t hungry. Maybe something else?

She brewed herself a last tea before bed. It was jasmine green, the same tea Nguyệt Uyển had made. She stood in the silent kitchen for a while, breathing in the smell of jasmine and grass. The visions were gone, for now, and her skin was her own, if a little too pale from lack of sun. She should go to the botanical gardens on her next day off.

Except… when had she last been able to go out for more than work?

She stared around the room. A small kitchen with an impeccable counter. Bookshelves. Flowers.

A routine. Colleagues she didn’t confide in. Friends she hid her Call from. No, worse. Friends she couldn’t even properly hear anymore.

How long had it been since she’d been able to have a conversation with Nga or Công? The Call had started to overlay everything a while ago. A long, long while ago, if she was honest with herself.

Have you no family?

You said you were all right. I’m glad you are. She lifted the teacup. She wanted to cry and she wasn’t sure why. She paused, the teacup at her lips.

Nguyệt Uyển.

Echoes of their conversation, of the ease with which it had happened, how she’d opened up in response to Nguyệt Uyển’s own confidences. A sudden, sharp, wounding realization, like a blade in her innards.

She’d had more connection to a lone stranger than she’d had with anyone in years.

She felt her hand start to shake.

She had Nga. She had Công. But… but every moment with them, she wasn’t telling the truth. Every moment with them, the Call encroached.

It would always be there.

Lâm thought of Nguyệt Uyển serenely pouring tea. Of all the other Descendants on their Paths, going hotel to hotel until they reached the sea and the dragons came to welcome them. Of Mother’s sigh of relief when she’d finally reached the water.

She drank the tea. As it left a trail of warmth down her throat, she felt understanding shift within her. She could wait and wait until the Call hollowed her out, keep living this half-life. Or she could go, abandoning her housemates as Mother had once abandoned her. She could keep on resisting until the bitter end—but what would be left of her, if she did?

It wasn’t that Mother hadn’t loved or cared for her. She had, as much as Lâm cared about Nga and Công. More, even. But, she thought, some things just were, like the calm at the end of a storm or the foam as a wave crashed on the sand. They happened, and the only freedom was what dignity to behave with and what kindness to extend to others. Neither Nga nor Công deserved to share the half-life Lâm was living, the constant exhaustion that no longer allowed for joy or true moments of community.

The Call was trembling at the edge of her thoughts—visions waiting to take over once more. She breathed in, and felt not serenity, not calm, but something like a weight settling on her. An acknowledgement of who she was. Of whom she was meant to be.

Descendant. Child of the dragon.

I’m scared, Lâm thought, and she felt like she was twelve again, watching Mother immerse herself in the harbor’s waters, watching her change. She was twenty, staring at the dragon over the prow of the ship, the moment trembling in the air. She was thirty-seven and watching the iridescent light playing in Nguyệt Uyển’s eyes.

Her hands shook again, unsteady. The tea shivered in her grasp.

She swallowed her mouthful and set the cup back on the counter, staring, for a brief moment, into its trembling depths. Then, before she could change her mind, she began writing a letter to Nga and Công, keeping it brief and factual, until she was ready to sign off.

I care about you deeply. I love you and I miss you already, but I have to go.

She left it on the table next to Nga’s cold soup and Công’s empty bowl of congee, where neither of them could miss it. They would be angry or sad; they would seethe at her lie and her lack of goodbyes in person, or weep for her or miss her. Or perhaps all of these.

But the wind was rushing once more, scales forming across the backs of her hands, waves rising up in front of her.

Lâm walked away, through the door, toward the streets lit by the rising sun, toward the hotels and the distant harbor, and, eventually, the fated sea.

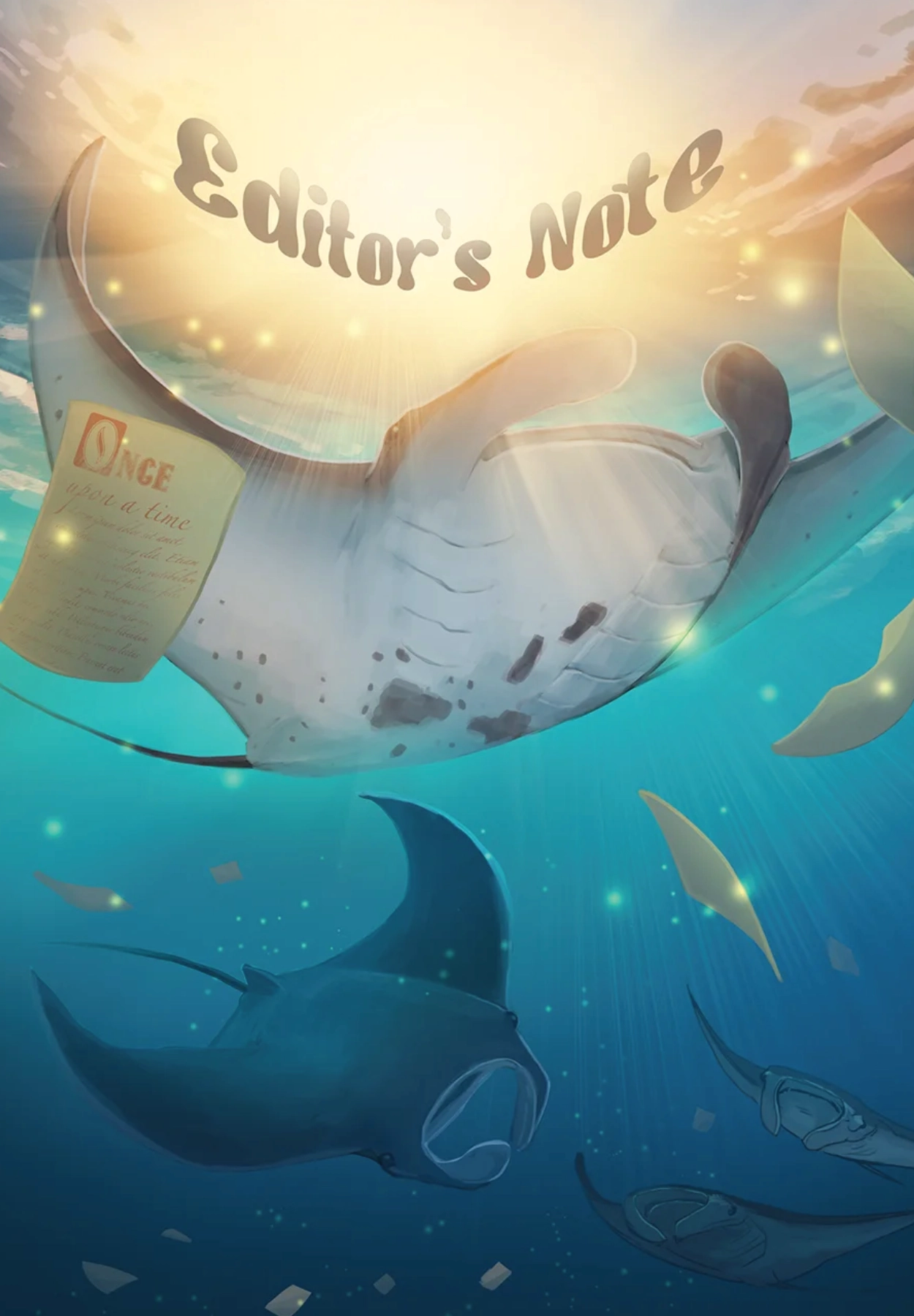

Dear lovely readers,

As regular readers of F(r)iction will know, this Editor’s Note is usually penned by our Editor-in-Chief, Dani Hedlund. This time around though, I’m popping in—Helen Maimaris here, at your service.

Why the change, you might ask? Well, before I get to the moment I hung suspended in the Pacific Ocean, tears filling my diving mask as I gazed upon my very first manta ray, let me introduce myself.

I started life at Brink—F(r)iction’s parent nonprofit—nine years ago as a wee publishing intern; by the time you’re reading this, I will have been one of Brink’s C-Suite Executives for seven years and F(r)iction’s Managing Editor for five. I live in the UK, and I’m a British-Cypriot mash-up (which mostly means that 1) I’ll likely accidentally slide the word “bloody” in here somewhere, and 2) I tan at the speed of light and think oregano and olive oil goes on everything). I’m an obsessive consumer of potatoes, love tropical heat, and am a confusing mix of simultaneously hyper-organized and pretty slapdash. But really, a vast proportion of my personality can be summarized by my two great passions: storytelling and the ocean.

Firstly, storytelling. As a child, I was most definitely a bookworm (so much so that interaction with other humans sometimes felt like an unnecessary hindrance, I mean honestly). No wonder really that I’ve spent my adult life working at a storytelling nonprofit. At Brink, I have the incredible privilege of overseeing our education programs that harness storytelling to transform the lives of our students, editing work with immensely talented authors, mentoring our senior staff team, and guiding our nonprofit’s vision and mission alongside one of the humans I most admire in the world. It’s not an exaggeration to say that every day, when I sit at my desk, I feel that same, intense pull that I get from reading, moments of joy akin to the breathless suspension of turning the first page in a book, the whole world falling away as your imagination lights up.

My love of the ocean plays out in seemingly less evident ways. It’s so core to me that I honestly don’t know when it began or why, but I like to think the spark was lit when I was just eight months old. My parents took me to Cyprus for the first time, ostensibly for my christening, but it was a baptism of a different kind that became pivotal. On that trip, I was dunked into the Mediterranean for the first time and that was that. Deep-Med blue is my favorite color, I’ve done volunteer scientific fieldwork in Ecuador with humpback whales during the mating season, I have been a professional-level scuba diver since my early twenties. I’ve dived with sea lions, manta rays, bull sharks, grey sharks, reef sharks, turtles; I know firsthand how the shifting mirror of the ocean opens up like a portal as soon as you drift past the surface and downwards, and that whether you’re exploring a shipwreck, gazing at the intense detail of a living, breathing coral reef, or drifting along in a current looking down into the deep deep blue, the ocean will never ever fail to awe.

So, when Dani suggested a couple of years ago that we curate an Oceans issue, I was ecstatic. Attentive readers may have noticed an odd trend in the artwork of previous issues—for years, the art direction team has been sneaking ocean details into F(r)iction illustrations, purely to hear my cries of delight when I spot them during our production meetings. Just one example: check out the space whales floating through the recent Dreams issue.

Then Dani proposed that I write this Editor’s Note and maybe mention her personal favorite ocean anecdote of mine. Share the magical moment when, on precisely my 194th dive, I first saw one of the most bizarre and beautiful animals imaginable after years of nurturing a, quite frankly, desperate longing to see one.

It was December 2019, and I was part of a small group diving a rocky site off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. We were near the end of our dive and thinking about surfacing soon when, from the hazy blue off to our left, a single, female manta ray emerged. She was huge, several feet across, and her fins moved gracefully up and down as though flying. The visibility wasn’t the best, but I could clearly see the lobes at the top of her head curving down in front of her mouth as her right eye tracked us. She circled our group once with a vast slowness before disappearing back into the mineral gloom. I realized then that I was crying into my mask—which, if you were wondering, is not where water goes and complicated seeing the actual damn, gorgeous thing. I’ve had the privilege of diving with many manta rays since, had a pregnant female pass just a meter above me, even floated in the midst of a “train” of tens of mantas. But something about that first teary time has stayed with me ever since. As the well-known saying goes, you never forget your first manta.

This is all to say that once Dani suggested I be the one to write this note, I thought, hell yes, I can’t wait to share my obsession with our readers to help frame the amazing content in this issue.

In these pages, we move around the globe to bring you poetry from a tsunami survivor; a feature from the eminent marine biologist, Dr. Ocean, illuminating the power of sunlight in the sea’s ecosystems; and a story exploring the ancient Vietnamese Con Rồng, or water dragons. We bring you a future world flooded after the waters rise, sci-fi that tracks a probe as it lands in the ocean of one of Saturn’s moons, a story delving into a DNA process that allows us to keep the ghosts of extinct animals alive, and a comic reimagining mermaid folklore. There’s also a feature showcasing work from several amazing storytellers over at Ocean Culture Life, an incredible nonprofit that brings people together from around the world to create an ocean community.

When I reflected on all these pieces, considering how they each explore the ocean through a different lens—whether fearful of its power, intoxicated by its vibrance, or turning to it as a beacon of hope—I realized that this diversity of experience was interwoven with one clear similarity: all these pieces surge with a deep, inexorable pull, a creative expression of the profound connection and undeniable fascination we humans have with the intense, shifting blue that surrounds us.

Safe to say, not only am I bloody proud of this issue, I’m also so excited to share it with you all that I can practically hear you oooing at the gorgeous art as you flip through these pages, despite the fact that I can safely assume, for the vast majority of you, we’re separated by a least a channel, or perhaps a sea, or most likely, a vast vast ocean.

And when I say separated, I mean connected. And when I say connected, I invite you into a moment of collective imagination: here we all are, wetsuitted up, tanks on our backs, hanging weightless in the blue, with the busy metropolis of a coral reef just below us, or perhaps the long fronds of a kelp forest surrounding us. We look up to see the wavering glow of the sun hanging above the surface, beams of sunlight cascading through the water like chandeliers. And in this moment, just like turning the very first page of a book you can’t wait to read, giddy with the joy of diving into the worlds within, everything is perfect.

Cheers,

Helen Maimaris

Managing Editor

Humans are hardwired for storytelling. Across our civilisations we have used narratives, as simple as cave paintings or as complex as multi-generational oral histories, to share knowledge, to imagine, and to thrive. The stories we cherish transform us. They point to our joys, our grief, our solidarity and our loneliness alike, guiding us through the chaos of being human. And as it turns out, there’s a science to stories.

From ancient myths to modern novels, the most enduring narratives follow core patterns that map to our inner lives, affecting the chemicals released in our brains and enhancing our capacity for problem-solving and empathy. We bond through stories, and we solve problems through the creative play that storytelling offers. In short: storytelling heals.

In the early 20th century, psychologist Carl Jung popularised the concept of the collective unconscious, a sort of inherited psychological landscape populated by mythic archetypes and shared by humanity’s unconscious mind. These archetypes shape us at a primal level and influence our self-development throughout life. That’s kind of a lot, so I’m just gonna call his theory ‘galaxy brain’.

Galaxy brain is impossible to prove on account of our not being able to witness the interior of every living person’s mind (thank the gods). But we don’t need to prove it to get behind the idea of a common mythic language. Jung’s symbols–the hero, the villain, the trickster, and the sage–conjure storylike images and associations in us that feel as fundamental as life itself. Examining the social and even biological aspects of this phenomenon are just as promising as trying to prove galaxy brain, and in fact, recent scientific breakthroughs have pointed toward just that

Scientists have confirmed that stories shape us at a neurological level. Brain imaging reveals that reading or hearing about an experience activates the same regions in our brains as experiencing it. Not only that, but when we are told stories, our levels of cortisol, oxytocin, and dopamine–neurotransmitters involved with memory, focus, and social bonding–measurably rise. These discoveries hint at storytelling’s power in facilitating empathy and imaginative problem solving. It makes sense then that our proclivity for telling tales has persisted when it’s linked to our essential human qualities. Stories quite literally open our minds and our worlds, and we share in their collective symbology, just like Jung posited. Maybe the real galaxy brain is the friends we made along the way. (Yeah okay, I’ll see myself out.)

We now know that ancient myths endure through the ages because they represent patterns of human experience. Persephone’s cyclical descent into the underworld gives shape to the rhythms of depression and renewal, while Icarus’s flight to the sun warns us of the dangers of unchecked pride. Writer Joseph Campbell’s seminal work—The Hero with a Thousand Faces—takes Jung’s mythic journey and grounds it in narrative convention for modern application by writers the world over.

The Hero’s Journey, or monomyth, follows a central character’s call to adventure through trials and an eventual, wiser return. Stories that follow this template hit because they serve as representations of our personal journeys. They resonate with us as we cross thresholds, face moments of uncomfortable self-reckoning, and claim boons as we transform our life experiences into hard-won wisdom. By combining the science of psychoanalysis with the art of storytelling, Campbell’s monomyth reveals how the most impactful stories provide a narrative container for our emotional healing.

Books aren’t the only place the storytelling power of the monomyth lurks, either. Traditional fortune-telling systems rely on the same premise, turning whimsy into therapeutic insight (or both! Both is good.) Author Liz Greene’s Mythic Tarot ties each card in the tarot deck to the Grecian classic myths, highlighting each myth’s depiction of psychological growth. The Fool’s leap becomes Dionysus, representing optimism and impulsivity, while Tower’s rubble symbolizes Poseidon’s wrath and the necessary collapse of outgrown defenses. Our Literary Tarot puts an even broader spin on this by pairing each card with stories from classic literature across the globe, in collaboration with modern authors. These symbolic systems take the building blocks of the monomyth and place them in our individual hands, encouraging us to make the Hero’s Journey our own. And hey–they’re fun!

When we grab our Hero’s Journey by the horns, we open to a world of imagination and introspection. Therapeutic writing—reflective journaling, letter drafts, poetry—lets us externalize pain and reclaim agency. When we recognize ourselves in fiction, we’re participating in collective healing, turning tales into both personal and cultural growth. At Brink, F(r)iction’s parent nonprofit, we harness this power to dismantle barriers and uplift justice-impacted people with our FRAMES Comic Program, where incarcerated writers craft stories around their personal experiences. Empowering one another to reflect, imagine, and express our core truths rewires perspectives and opens new pathways in minds and lives alike.

As we tell and re-tell our stories, we build on our collective understanding, not just of symbolic archetypes but of each other. Plugging our own experiences into the monomyth gives us agency. Reimagining old tropes from new perspectives contributes to our shared knowledge. And listening when someone tells you their story builds a bridge between you that might change both of your lives for the better, transforming inner burdens into real moments of human connection. This is where the healing potential of stories shines brightest: in the space between speaker and listener, belonging begins.

‘The Power of Stories’ is a limited blog series exploring the ways stories weave themselves into the fabric of our lives. It’s an invitation to reflect on how narratives—whether passed down through generations or splashed across the big screen—shape who we are, how we connect, and the worlds we imagine. Each post peels back a new layer of storytelling. Next up we’ll explore how stories shape identity, community, and culture.

“You are what you eat,” but what about what you read, watch, or scroll through? Stories are sustenance. They entertain us, feed our curiosity, and challenge our assumptions, shaping the way we see the world. Some cater to our tastes while others expand them, and many do both… when we take our time to savor the flavor. In a cultural moment of constant content, where storytelling’s traditional gatekeepers are increasingly influenced by algorithms and paid promotion, now is the perfect time to get curious about fueling ourselves in a way that’s energizing and livening.

It’s the 21st Century. We have access to more stories than ever. Representation and publishing are reaching for new and broader horizons—and rightfully so, we think—that’s what F(r)iction is all about. But endless access begs new questions for modern readers. Is it okay to love The Lord of the Rings while critiquing its outdated tropes? Can we enjoy Alien’s gruesome thrills while dissecting its capitalist subtext? Are you a fanfiction-turned-erotic-fantasy convert, and have you ever been ashamed of it? (Psst–you shouldn’t be!) With our devices’ instant offering of stories both new and familiar, exploring our media palates enables us to discover the flavors in every piece.

Like many a word nerd, I’ve a lifelong love of fantasy. It is uplifting and transporting, taking us on sweeping adventures through vividly-imagined worlds. It’s also notorious for distilling moral complexity into binary extremes: noble kings versus monstrous baddies, pure heroes against irredeemable villains. This is the genre’s meat and PO-TA-TOES—simple and gratifying. But the real world is juicier, and the best fantasies know when to bake in that extra juice.

Tolkien’s moral contrasts in The Lord of the Rings are unmistakable, but its fans will tell you they’re not the whole meal. The epic’s power emerges in the fragile bonds between unlikely allies—alliances between elves and dwarves, the loyalty of Sam to Frodo, Middle Earth’s shared fight for a world worth saving. The legendary battles and enchanting magic of Tolkien’s world are revelatory, but its relationships—complex, messy, and deeply human—are the sustenance that keeps us coming back for seconds (and thirds, and fourths… I see you!).

Horror is another genre ripe for the picking. These stories go all in to grip us with primal thrills—the shock of violence, filth, and the visceral dread of the monstrous Other. But there’s more meat to be had for the hungry. Horror holds up a mirror to mankind’s shadowy impulses and taboo topics, inviting us to reflect on what really frightens us: the monster, the conditions that created it, or ourselves? (Hint: yes.)

My favourite example is the films Alien and Aliens. They’re a masterclass in terror—xenomorphs bursting from chests, the iconic Ellen Ripley’s desperate flight through the Nostromo’s corridors. But the xenomorphs are weaponized by the Weyland-Yutani corporation, a human creation, to further their medical and military advancements. That origin story’s not all that, well… alien. Ripley and the xenomorph queen are eerily mirrored by their need to adapt to and survive the invasion of the same colonizing force. The facehuggers get your attention, but that message sticks to your ribs.

Sometimes a story’s purpose is to thrill and delight, and at first glance, it kinda seems like that’s it. Is it, though? Sarah J. Maas’ A Court of Thorns and Roses series combines swoon-worthy tension with glittering worlds, for instance, offering the best of fantasy’s enchantment and romance’s emotional payoff. Oft criticized as indulgent, Maas’ emphasis on female desire and agency has galvanized a generation of readers while sparking censorship debates for her erotic content. Fan or no, it’s hard not to see the spice there.

Similar can be said for the staple horror franchise Friday the 13th. Some of us crave a good ol’ fashioned slasher, and Jason has faithfully delivered since 1980. The mask is emblematic, the kills are creative, and the most pressing question on our mind is who makes it out alive (if anyone). But Friday the 13th did something unprecedented for the genre–it distilled slasher horror to a single fundamental: no victim backstory, only killer mythos. This reduction, condemned as gratuitous, weaponizes the audience’s indifference, mirroring Jason’s psyche and providing viewers a brand-new experience in confronting fear. Jason is proof that even stories stuffed with tried-and-true stereotypes can yield surprising substance when we really sit down to eat.

At F(r)iction, we believe stories should nourish as deeply as they entertain. That’s why we publish stories with substance: the kind that tantalize your tastes while sustaining empathy, challenging assumptions, and leaving readers fortified for the world beyond the page.

The Power of Stories is a limited blog series that dives into the ways stories weave themselves into the fabric of our lives. It’s an invitation to reflect on how narratives—whether passed down through generations or splashed across the big screen—shape who we are, how we connect, and the worlds we imagine. Each post peels back a new layer of storytelling, and next in the series delves into a F(r)iction favourite, the therapeutic power of stories.

There’s a certain magic in opening a book, pushing play, or plunging into an immersive video game and feeling the world around you fade away. For a moment, the weight of your to-do list, the hum of your worries, and the noise of the everyday dissolve. You’re no longer just you—you’re a hobbit setting off on an unexpected journey; a space explorer probing uncharted galaxies, or a detective unraveling a mystery that keeps you guessing until the very last page. This is the power of escapism, and it’s far more than just a way to pass the time. It’s a lifeline, a sanctuary, and sometimes, a source of hope.

J.R.R. Tolkien, the mastermind behind The Lord of the Rings, once defended escapism as something more profound than mere avoidance. He argued that escaping into stories isn’t about running away from reality—it’s about finding the strength to face it. In his essay On Fairy-Stories, Tolkien wrote, “Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls?” Stories, in this sense, are a form of liberation. They remind us that there’s more to life than the walls we sometimes find ourselves trapped within. They offer us a glimpse into our essential humanity—where courage triumphs, where love endures, and where even the smallest person can change the course of the future.

But escapism isn’t just about connecting with our inner worlds. Sometimes, the most powerful escapes are the ones that reflect the external world back to us. Take, for example, the growing representation of minority perspectives in media. Stories like Heartstopper, which explores queer joy and self-discovery, or The Hate U Give, which tackles systemic injustice with unflinching honesty, provide more than just an escape—they offer a roadmap. They show us that even in the midst of struggle, there’s room for growth, connection, and resilience. These stories don’t just help us escape; they help us return to our own lives with a renewed sense of purpose and possibility.

And then there’s the solace of shared experiences. Have you ever read a line in a book or watched a scene in a movie that felt like it was written just for you? Stories offer us the realization that we’re not alone in our thoughts, our fears, and our dreams. As actor and author Alan Bennett, best known for exploring the isolation of the mind in his play The Madness of King George III, once wrote, “The best moments in reading are when you come across something—a thought, a feeling, a way of looking at things—which you had thought special and particular to you. Now here it is, set down by someone else, a person you have never met, someone even who is long dead. And it is as if a hand has come out and taken yours.” That’s the magic of storytelling: it bridges the gaps between us, connecting us across time, space, and experience. It reminds us that our struggles, our joys, and our hopes are part of the larger human tapestry.

Escapism, at its core, is more than just distraction. It’s about finding the courage to imagine a better world—and, in doing so, finding the strength to create it. Whether it’s through the pages of a book, the glow of a screen, or the shared experience of a story told aloud, escapism offers us a chance to recharge, reflect, and reconnect. It’s a reminder that even in the darkest of times, there’s light to be found—and sometimes, that light comes from the most unexpected places.

So, the next time you lose a day binge watching your faves, don’t feel too guilty. You’re not just escaping; you’re healing. You’re exploring. You’re finding the tools you need to keep going. And who knows? The story you escape into today might just be the one that helps you change your world tomorrow.

The Power of Stories is a limited blog series that dives into the ways stories weave themselves into the fabric of our lives. It’s an invitation to reflect on how narratives—whether passed down through generations or splashed across the big screen—shape who we are, how we connect, and the worlds we imagine. Each post peels back a new layer of storytelling, and next up we’re digging into storytelling as food; from what fuels us creatively to the importance of curating one’s own ‘media diet.’

Everyone writes the story of their life, so I write the story of my life! What do you think? Will the story of my life be about my whole life? I will tell you my story.

I am telling you about the beginning of the misery of an Afghan girl. Listen to me. The year was 2021, August 15th. It was a terrible day. All the people, men, women and children were all scared, because the Taliban had reached the capital of Afghanistan, Kabul.

On that day I was alone at home and my family was outside. When I heard that the Taliban had reached Kabul, my hands and feet began to tremble, and my mental state became very bad. I was crying while my body was trembling.

Then my family came home early that day. My 3-year old brother was in kindergarten and one of our friends brought my brother to us. We were all scared and I kept repeating to my mother while crying,

“Please Mother, let’s go from here, please Mom, please.”

My mother was trying to calm me down, but I kept crying and saying, “Let’s leave here, please.”

Then my mother decided that we should go to the American Embassy.

When we arrived at the American Embassy, there were no guards at the gate. When we reached the second gate, there were two guards there and they did not allow us to enter until a woman with her little son and two American men came and helped us in. We reached the third gate with those men and women. There was also a guard there who allowed the American people to enter the American Embassy. The third gate was next to the American Embassy airport, but we were not allowed to enter.

The woman with her son and the two American men showed their passports to the guard and the guard allowed them to enter, but did not let us go with them. The guard was an Afghan man. He told us that we were not allowed to enter the embassy because you do not have a US visa or passport.

We were waiting for those men and women in front of the third gate near the American Embassy airport. After a few minutes, they came back but without talking. They quickly went to the airport and didn’t even look at us because they couldn’t do anything for us.

After a few minutes, we left the place disappointed and went home again. That night I didn’t even take off my shoes because I wanted to leave Afghanistan. We had no idea what was going on at the Kabul Airport.

On the second day, August 16th, my aunt called us from America and said, “You don’t know what is going on at the airport,” and she told us to go to the square and enter the square by a certain way. We moved towards the airport. When we arrived at the airport, there were many people there, more than a thousand people. The Taliban held the airport gate and did not allow anyone to enter the airport. The situation there was very scary and bad. Men, women and children wanted to get out of Afghanistan. No-one wanted to live under the shadow of a terrorist government. Everyone was scared and the Taliban asked people to return to their homes. When no-one listened to their words, the Taliban fired their weapons into the sky so that people would be scared and go to their homes. They did nothing to families but they were very cruel to unmarried boys and beat them with whips and guns. A number of single young men were beaten so hard that their arms and legs were broken or their heads were injured. And they electrified a number of men.

We waited in front of the gate until it got dark. We were waiting for them to open the gate but unfortunately the gate was not opened and we returned home.

The next day, August 17th, in the afternoon, we went to the back gate of the airport. There were a lot of people there, too many. We stayed there overnight, then it was morning but the guards did not allow us or anyone else to enter that morning. We left there with disappointment and came home. We all fell asleep very tired and we didn’t go to the airport any more.

That night came and we learned of a very heavy explosion in front of the back gate of the airport, the same gate where we were the night before until the morning. We found out that hundreds of people were killed and four American guards were killed. We looked at the TV and saw human bodies lying completely covered in blood near the gate on each side! I thought to myself that if we’d been there that night, we would be among the victims of the explosion, and this thought made me feel very bad.

I was very disappointed and wondered what would happen to my future. I was very worried that the Taliban would force girls to marry like 20 years ago. My biggest fear was losing my future and it was very worrying for me.

On August 20th, my mother met a lady on the internet, her name was Helen*. She was a kind lady. She included my mother in a group that day to help us and the name of that group was the UK Afghan Midwives Support Group. They gave us financial help and supported us.

During those days, all the people we knew had left Afghanistan, like my grandmother and grandfather, my aunts and my uncle. We were the only family that remained in Kabul in the first days. My grandmother used to call us and say that everything will be fine, there is a light behind the darkness, but I said that I have no hope in response to my grandmother. I used to say that from this day on, in my opinion, Afghanistan is a playground where any power can play with the Afghan people as much as they want. They started this game 20 years ago and people worked like game workers, and this game started again and we returned to 20 years ago. So Afghanistan is a playground and we are its workers. After hearing my words, my grandmother became silent and looked at me with surprise and said,

“You are right.”

Until the day I die Afghanistan will always be a playground in my opinion. I always said this to myself: “Whoever is wise will not destroy the future generation of Afghanistan, but they will leave Afghanistan because we will be under a Taliban government for 5 to 10 years, then the Republican government will come again, and then in 20 years the Taliban will come again”.

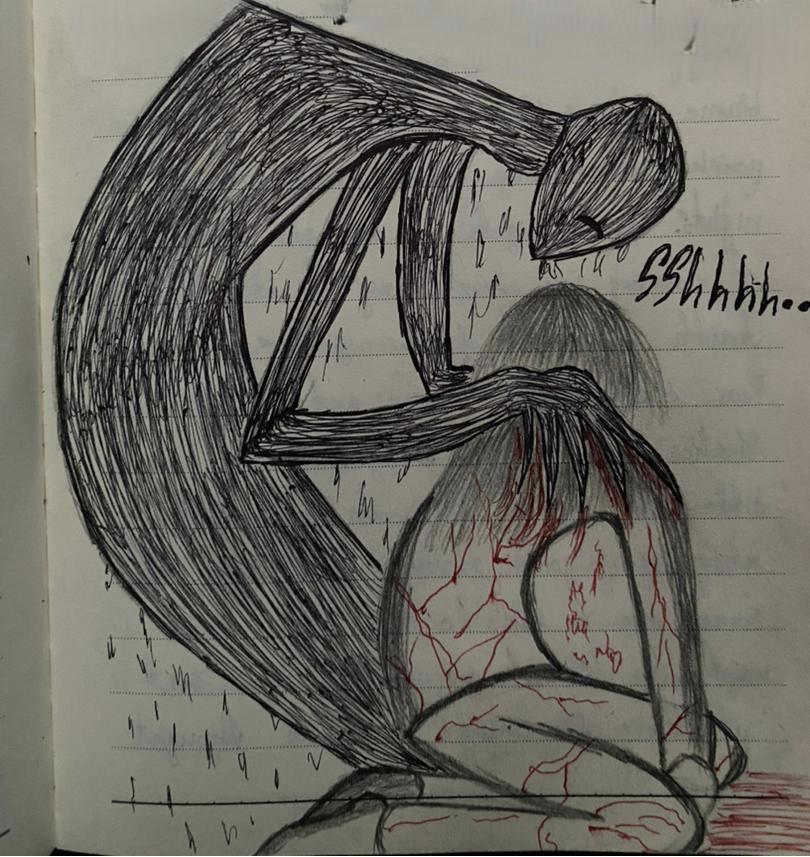

My mental health had completely disappeared, I had become a depressed and hopeless girl, a girl whose wings were cut off, a girl who buried her dreams, a girl whose life no longer had meaning for her. This was my biggest fear. I was a sad girl, a girl whose dreams had died, a girl with no hope for life in the future, and I was burning like a candle from the inside for my black future.

Do you think I was the only one who had this feeling? This feeling is shared by all the Afghan girls who were striving for their progress and bright future.

At first, the Taliban closed the school gates to girls and darkened the way of light for the girls. In those days my mother told me that Helen said they had made a case for us and were trying to get us resettlement in England. I found hope after hearing these words from my mother. My brothers and I were very happy and we were thinking that we will get out of Afghanistan soon. Every day we thought about having a good and happy life and a bright future in England and achieving our educational goals. We were dreaming about what we would do when we went to England.

I had a dream with myself that when I go to England, I will start my studies first and work with my family, and after 2 or 3 years I will be able to buy a car because I would really like to have my own car.

My little brother said that when we go to England, he would like to play in the park there and go to the beach and play in the water because he loves the beach and the ocean. My elder brother also wished to complete his education in England and become a good doctor in the future for the people. I also want to become a good doctor in the future so that I can help people in a good way.

My mother was very happy when she saw me and my brothers happy. My family and I thought that maybe we would be out of Afghanistan in 6 or 9 months and, as the days passed, we waited.

Helen and the group always paid attention to us and helped us and did not let us feel bad about anything. They sent us money every month and always supported us during those days.

My mother also met Helen’s sister. She was also a very kind and heart-warming lady, her name is Sarah. She always encouraged us and loved us like her own children. She always asked us if we had enough food to eat or if we needed anything else. When we needed something, she asked Helen and the group to meet our needs.

Again, the days and nights passed and we were waiting for the light of our life for a long time and it was getting tiring to live like a prisoner in your own country and not to be able to walk and breathe freely or to follow your own dreams.

Months passed and there was no news about our case. I was slowly, slowly losing hope. Meanwhile Helen and the group were doing their best to get us out of Afghanistan. My mother was in communication with Helen and Sarah every day.

After some time, my mother became very close with Sarah and they used to talk a lot. They talked about our problems and Sarah always gave my mother hope that we would leave Afghanistan.

Days and nights passed and the relationship between my mother and Sarah became closer day by day. Sarah always loved us very much until one day she said,