November Staff Picks

Dominic Loise

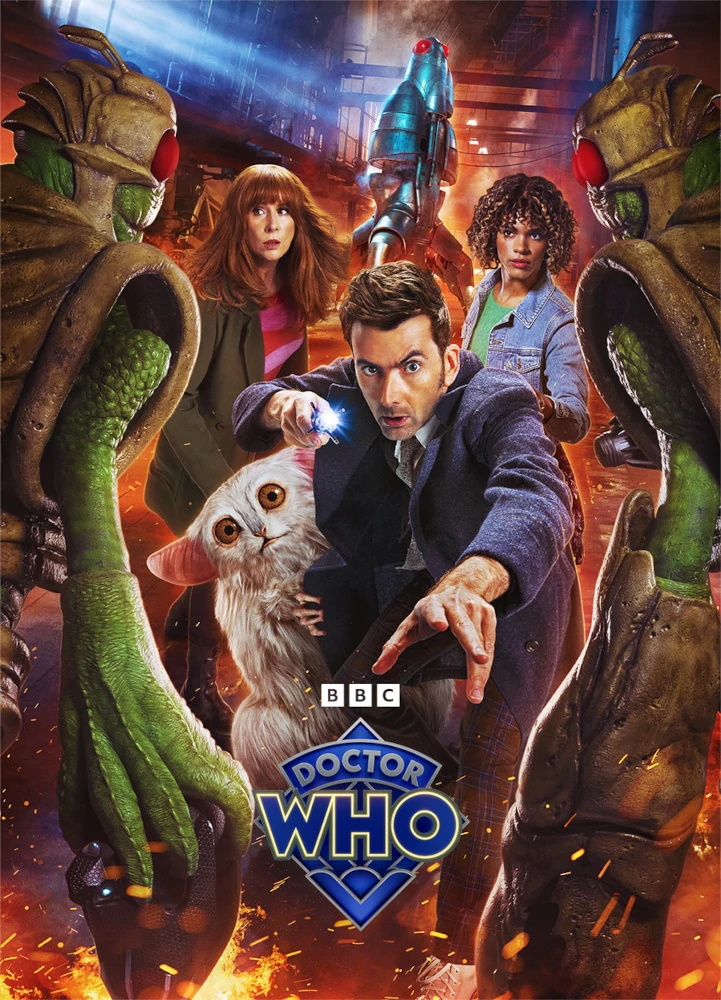

Doctor Who: The Star Beast

Doctor Who: The Star Beast just landed for the BBC’s sci-fi series sixtieth anniversary. The Star Beast ties in a lot of the show’s history in the special. For those unfamiliar with Doctor Who, it’s about a runaway alien with two hearts and a screwdriver traveling time and space fixing things that have go wrong.

The sixtieth anniversary special has big connections to past Doctor Who eras like the return of beloved actors and showrunners. It wouldn’t be a recent Doctor Who landmark anniversary without David Tennant returning to the role of The Doctor like he did for the fiftieth anniversary. Also returning this time, we have Catherine Tate as companion Donna Noble and writer Russell T. Davies, who relaunched the show in 2005.

Davies, Tate and Tennant bring a satisfying conclusion to the Doctor/Donna cliffhanger from their original run on the series and Davies writes a show which has an updated queer perspective for 2023 just like he did during 2005. For example, Davies original run on Doctor Who gave us the lgbtqia+ iconic character Captain Jack Harkness, who went on to star in his own series Torchwood. Doctor Who: The Star Beast introduces us to Donna’s daughter Rose Noble and this special is Rose’s human story as much as it is The Doctor & Donna’s adventure tale.

The Star Beast also honors Doctor Who’s history by adapting the story from one of the classic comics book stories, which was illustrated by Dave Gibbons (The Watchmen). The look of this special is comic book bubbly as the creators remember that Doctor Who is first and foremost a kids show for the whole family. To quote The Doctor, “There’s no point in being grown up if you can’t be childish sometimes.” Doctor Who: The Star Beast is just what this longtime Whovian needed for their inner child.

Kaitlin Lounsberry

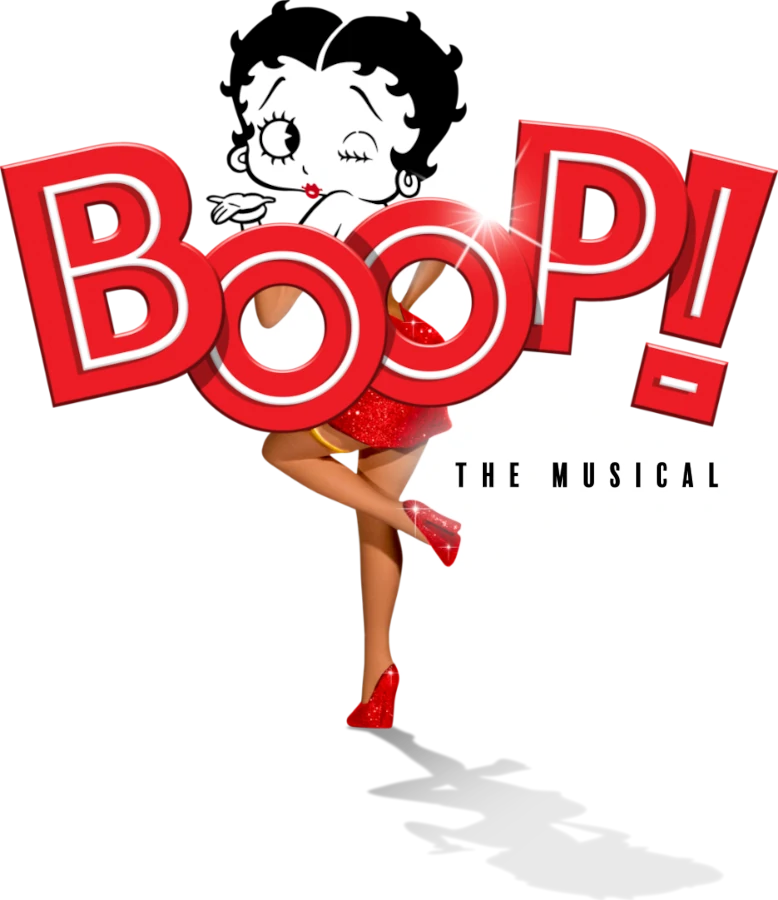

BOOP! The Musical

With the saturation of the music theater, it’s rare I find myself gob smacked by a new play. I’ve seen a LOT of Tony-winning musicals in my life (Hamilton, Dear Evan Hansen, Chicago, and Wicked to name a few) so I feel as if I have a good sense when I’ve stumbled upon a stellar play. Enter BOOP! The Musical, which delivered one of the best theater experiences I’ve had in years. Currently on the pre-Broadway track, BOOP! combined everything I, personally, look for in a play. Stunning costumes? Check. Engaging plot that didn’t leave me restless halfway through? Check. Musically gifted cast? Triple check. What, or rather, who impressed me most, though, was Jasmine Amy Rogers. She literally embodied Betty Boop. From Betty’s mannerisms to her voice to her sassy, but sweet attitude towards life, Rogers captured the character and reminded me why Betty Boop has been a beloved animated character for decades. So, if you happen to find yourself in the Chicagoland area sometime in December and are looking to be dazzled, swing by the CIBC Theater for a Boop-oop-a-doop time.

Gina Marie Gruss

Scavengers Reign

I love aliens. Give me aliens of all types, but in my mind, the more experimental (and less humanlike), the better. Give me alien landscapes. Alien physics. Alien worlds. Aliens.

Scavengers Reign gives me aliens in all ways—and executes the concept of “alien” flawlessly. It’s set on a strange world with diverse landscapes and amazing creatures. It does centralize the human experience, of course—it sells me on high stakes and drama and humanity, following a crashed spaceship’s passengers as they try to survive and get back home—but it’s also set against one of the coolest places I’ve ever seen. It’s a slowburn; it takes its time with the characters and environment. It’s rewarding. (I mean, I selfishly want more, but its ending is satisfying—it’s a miniseries.) And did I mention that it has one of the coolest aliens and planets I’ve ever seen? I’m so excited that there’s more mature animation being produced! (Though it is ironic that it’s published on Max (formerly known as HBO Max).) I came to Scavengers Reign for the aliens. I stayed for the humanity.

Nate Ragolia

The Glass Cannon Podcast

As a tabletop gamer, I love the collaborative storytelling that emerges in the boundaries of a campaign. Through the rules of a system like Dungeons & Dragons, Pathfinder, or others, a group of creative people can create, shape, and thrive in a magical, mystical world just by bringing a character to play, embodying them, and reacting as they would to the chance inherent to each roll of the dice.

I’ve been listening to The Glass Cannon Podcast for a few years now. I got invested in their first campaign, Giantslayer, after listening to a few episodes in 2017, and immediately started working my way through the story from start to finish, some 326+ episodes later. Now, with a whole network to their name, the Glass Cannon Podcast family are embarking on a brand new campaign titled Gatewalkers. They are only 12 episodes in now, so this would be as good a time as any to jump on board.

If you love tabletop gaming, or you just enjoy the cozy vibes of friends crafting story together while fighting monsters, cracking wise, and crying out in joy and sadness, this podcast just might be for you. It’s full of laughs and well-constructed tension (both within the story and between the hosts), and they take their stories and characters seriously, imbuing them with meaningful arcs and character growth that can set this podcast apart from other tabletop gaming shows. Plus, they’ll give you thousands of hours of entertainment for free… so what do you have to lose in checking it out?