If you’ve ever met one of our wonderful F(r)iction staffers, you’ll quickly learn that almost every one of them was once an intern in our Publishing Internship Program.

This program is run by our parent nonprofit organization, Brink Literacy Project. While our publishing internships are a great way to get a crash course in the literary industry, they can often provide a path to what can become a long and rewarding professional relationship. For more information, please visit the internship page on the Brink website.

Ainsley Louie-Suntjens

she/her

Where is your favorite place to read?

My favorite place to read is cozy in bed, in my room, with ambient lighting and lots of pillows and blankets. It’s even better if it is raining or snowing outside. A close second is on the beach in the sun.

You’re walking up the side of a mountain along a winding, wooded path. You look to your left and discover, by chance, a door in the side of the mountain. Do you open it, and if so, where does it lead?

After a little bit of anxious waffling, I would open it because I would regret it if I didn’t. Behind the door, I hope to find Wonderland, complete with talking cards and chess pieces and mad tea parties, but knowing my luck, I would find the Other Mother. Not that I’m complaining. That would be really cool in its own way.

How do you take your coffee? If you don’t drink coffee, describe your favorite beverage ritual.

I take my coffee double-double: two milks, two sugars. If I’m feeling fancy, I’ll add some chocolate or caramel syrup.

What is your favorite English word and why? Do you have a favorite word in another language?

I think my favorite English words are “banshee” and “gossamer.” They’re really fun to say aloud and they are striking on the page. The way they sound remind me of an adagio on strings, and that sort of reminds me of ballet. I think they are also beautifully descriptive and create a whole compelling image in your head the minute you read them.

You’re on a deserted island. You have one album and one book. What are they and why?

This is cruel question, but if I had to my one album is Preacher’s Daughter by Ethel Cain and my one book is The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. Preacher’s Daughter poignantly and rendingly explores the horror and triumph of womanhood, love, devotion, and rage, and I think to some extent, The Bell Jar does too. I could listen to these songs and read this one book over and over, and still get something new out of it every time.

If you could change one thing about the literary industry, what would it be?

I would create more properly paying entry level jobs. On a fiscal level, it isn’t the most realistic of ideas, but it is so difficult to get into publishing if you are working-class. So many people have such a hard time getting into the industry just by virtue of the fact most entry-level positions are unpaid volunteer jobs, and it is hard to justify doing such work if you don’t already come from some degree of financial privilege, or at least stability. In turn, it can shut out the people who need to be heard most urgently in this industry. It is a self-perpetuating cycle that I would like to break.

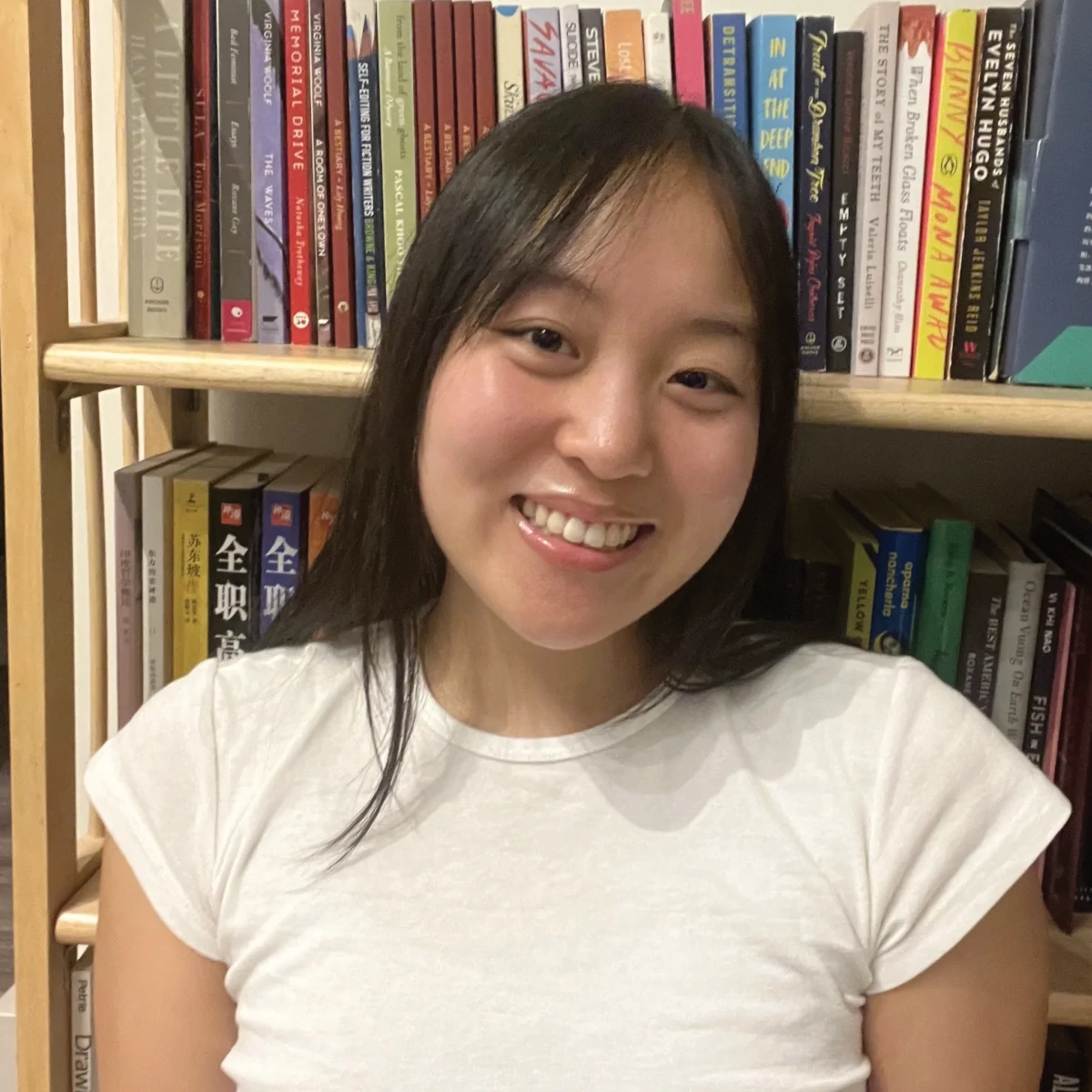

Erxi Lu

she/her

Where is your favorite place to read?

I love reading in the quiet. In a more physical sense, I enjoy reading on my blue bean bag and feeling myself sink into both the ground and the words on the page.

You’re walking up the side of a mountain along a winding, wooded path. You look to your left and discover, by chance, a door in the side of the mountain. Do you open it, and if so, where does it lead?

At first, I would hesitate. What if the door leads to a dangerous path? Unbeknownst to me, my index finger would push the door open, and I would see a beautiful winding staircase with bookshelves lining walls that seem to extend forever above and below me. The staircase makes the universe feel unfathomably large, yet also comfortably small.

How do you take your coffee? If you don’t drink coffee, describe your favorite beverage ritual.

No coffee! My favorite and most frequently consumed beverage is cold water from a refrigerated Brita pitcher peppered with ice cubes. I love chomping on ice!

What is your favorite English word and why? Do you have a favorite word in another language?

My favorite words in English are the ones that sound juicy, like bursting, slurp, and crunchy. There are just some words in English that are incredibly fun to say. I’m not sure if I have a favorite word in Chinese, but recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about words that are difficult to translate into English. For now, it is 心疼.

You’re on a deserted island. You have one album and one book. What are they and why?

The album I would bring is 平凡的一天 by 毛不易. In English, the album is An Ordinary Day, but also known as a Perfect Day in English. 毛不易’s voice is calming, as he equates normality with perfection and beauty. I think his calming voice would make the deserted island feel a little less deserted and lonely. I would bring Imagine a Death by Janice Lee as my book. It’s a book I recently discovered last year and has the experimental writing style that I find to be delicious!

If you could change one thing about the literary industry, what would it be?

I wish there was a larger focus on experimental writing and playing with language, rather than “selling.”

Lydia Layton

she/her

What is your favorite place to read?

At the beach on a hot day, having just swam in the sea. Fresh air, and fresh perspectives—just right.

You’re walking up the side of a mountain along a winding, wooded path. You look to your left and discover, by chance, a door in the side of the mountain. Do you open it, and if so, where does it lead?

I’d open it to find a vast, undiscovered planet of beauty and adventure. And the keys to a truck that’ll drive me anywhere I want to go while I’m there!

How do you take your coffee? If you don’t drink coffee, describe your favorite beverage ritual.

A cappuccino in the morning (even better with a croissant), and a macchiato for afternoons; always taken with one sugar or less.

What is your favorite English word and why? Do you have a favorite word in another language?

Synaesthesia. It has multiple satisfying repetitive sounds and describes a fascinating human phenomenon too.

You’re on a deserted island. You have one album and one book. What are they and why?

Pink Moon by Nick Drake would be the soundtrack to my island isolation. I hope, eventually, I could fashion a guitar from a tree and learn to play the tunes myself. A new hobby, and some great music to enjoy, all-in-one.

And a book —The Picture of Dorian Gray —a strange, spooky classic.

If you could change one thing about the literary industry, what would it be?

I would challenge the assumption that the “average consumer” is most often not interested in abstract or complex ideas within literature. In many cases, individuals are interested in learning but disadvantaged by their lack of educational opportunity. When narratives are written with accessible communication in mind, simple stories can be infused with big ideas and inspire intellectual and creative progress among people that otherwise wouldn’t have been exposed to them.

Parker McCullough

he/him

Where is your favorite place to read?

I like to read in the comfort of my bed after a hot shower with fresh, clean sheets. I tend to read right before bed, which is ideal for me. It helps me relax and regulate myself.

You’re walking up the side of a mountain along a winding, wooded path. You look to your left and discover, by chance, a door in the side of the mountain. Do you open it, and if so, where does it lead?

Honestly, I don’t think I would be in this situation. I’m not the type to hike up a winding mountain path. I prefer flat land and being securely placed on the ground at all times. Additionally, if I WERE to be in said situation, I probably wouldn’t open the door. What if there was an ancient wizard prepared to task me with my life’s greatest, most dangerous mission? I’d rather pass. The less I know, the better. Onward.

How do you take your coffee? If you don’t drink coffee, describe your favorite beverage ritual.

What was it that Hozier said about taking his whiskey neat and his coffee black? Not to brag about being dark and mysterious (it’s my Scorpio rising), but I have to agree with that line. I’m a no-frills type of guy.

What is your favorite English word and why? Do you have a favorite word in another language?

I’ve never actually thought about this! I would have to say my favorite English word would be “queer.” It encapsulates so much but is simultaneously so vague. It’s like when you hear the word regarding identity, you can easily picture something or someone eccentric, out of the norm, unexpected, but you can’t quite put your finger on what exactly it is. I love the room for nuance and indefiniteness the word invites. It creates space for interpretation, because to me as a nonbinary person, nothing is ever black and white, one thing or the other. My favorite word in another language is “muyè.” It is Haitian for “mother.” I first heard the word while mixing a song called “Muyè” by Keinemusik. I urge you to play the song and go where I went while listening.

You’re on a deserted island. You have one album and one book. What are they and why?

The one book I would have would be the Holy Bible. I tend to read it when I feel lost or uncertain and being on a deserted island might guarantee those emotions. The one album I would have would be Blonde by Frank Ocean. That album is 100% playback-worthy and helped me come into my queerness.

If you could change one thing about the literary industry, what would it be?

I would seriously change the literary industry to be more inclusive to BIPOC, queer/trans, and low-income individuals. We need to level the playing field. White, privileged, able-bodies tend to get priority and access to these amazing opportunities. Many minorities, including myself, are not privileged enough to drop everything and move to New York with my parent’s trust fund in hopes of landing that dream internship that is unpaid. I grew up in the south side of Dallas, Texas. Statistically speaking, I was never meant to break away from the generational trauma of my family and bloodline, escape to Chicago, graduate with my MA in Humanities from the University of Chicago, and begin my dream internship. I am structurally meant to fail. However, I overcame the systematic struggle to get to this point, and I did it all on my own, without much financial support from my family or society. I have come to believe that I am some sort of anomaly, the exception to the rule, much like very few others. This is why I care so much about giving back to the communities I come from. It’s a shame that the literary industry is not more inclusive in giving opportunities to underprivileged/QT black and brown voices because we have so much to offer, so much to give. It is truly a well of untapped talent and skill with a valuable, unique perspective on literature and writing. All it takes is for someone to give us a chance.

Skyler Boudreau

she/her

What is your favorite place to read?

My favorite place to read is in my bed next to my window curled up under a blanket. If it is raining outside, that’s even better.

You’re walking up the side of a mountain along a winding, wooded path. You look to your left and discover, by chance, a door in the side of the mountain. Do you open it, and if so, where does it lead?

If I found a door in the side of a mountain, I would have to open it because I would spend the rest of my life wondering what could have been behind it. Hopefully, the door will lead me to the ancient, magical library in Erin Morgenstern’s novel The Starless Sea, and not into the lair of a disgruntled dragon.

How do you take your coffee? If you don’t drink coffee, describe your favorite beverage ritual.

One of my favorite beverages is lemonade, specifically the lemonade made by The Teatotaller, the best café in New Hampshire. I love spending summer afternoons drinking their berry-flavored lemonade and playing board games with my friends at our favorite table.

What is your favorite English word and why? Do you have a favorite word in another language?

My favorite English word is “discombobulated,” because it concludes some of my favorite sounds in the English language. My favorite French word is trente-et-un. It means thirty-one. I love the way it rolls off the tongue!

You’re on a deserted island. You have one album and one book. What are they and why?

If I were stranded on a desert island with one album and one book, I would have to choose Hozier’s Unreal Unearth album and When Women Were Dragons by Kelly Barnhill. All of Hozier’s albums are excellent, but Unreal Unearth is especially dear to me because I am fascinated by the way each song on the album comes together to paint an overarching story. When Women Were Dragons is a beautiful, but rage-inducing novel that reveals a new theme each time I read it. Between When Women Were Dragons and Unreal Unearth, I think I will be kept entertained for a while!

If you could change one thing about the literary industry, what would it be?

I think the literary industry has made several positive strides over the past few decades. However, there is still a long way to go. If I could change one thing about it, I would make the literary industry more representative of its audience. There are a lot of important stories that still need a chance to be told.