Kim killed herself. She thought about that—the implications of it—and knew there was a saying to describe what she felt. It took her a moment to remember what it was. When she did, it struck her as strange—both more alien and more starkly literal than it had ever felt before. The saying was this: she couldn’t wrap her head around it. She stood there, in the kitchen, looking down at her own body on the floor and felt her head try to wrap itself around a fact that was too big and too shapeless to be surrounded.

She was afraid that if she touched the body—the body that was certainly her own—something bad would happen, so she just looked at it. She was still holding the heavy iron frying pan she’d used and she lifted it to have a look. There was a black smear on one side that she knew was blood and she was tempted to taste it to be sure but decided against it. She was pretty sure the frying pan was real, which meant the blood was real which meant, in turn, the body on the floor was probably real too. That meant Kim had killed herself. She thought about that. She thought about it a long time but she never could wrap her head around it.

This wasn’t the first strange thing to happen. The first had been a phone call she’d received maybe a week prior. She wasn’t sure about the timeframe. She had been huffing paint at the time. This was something she did. She had just taken in a big wet snozzlefull, the kind that settled in behind the eyes, hot and itchy and cooking her brain like cheese on a hotplate when the phone rang. It took her a long time to realize what was happening, but when she finally answered she heard her own voice coming out of her even before she was aware of speaking. “Hello,” she said.

“Um, hello?” said the voice on the other end of the line. It was her voice too. They both were. It was confusing.

“I’m calling you from…are you…alright?” the voice said.

Kim was standing in the kitchen but her legs felt like they were dangling off the edge of a very steep drop. She wasn’t sure how to answer.

The voice continued. “I didn’t think you would pick up.”

“I did pick up,” Kim slurred.

“I’m calling because I think I killed you.” The voice sounded unsure. “Or maybe I haven’t yet. Maybe I’m in the future.” There was a lot of feeling in that voice and Kim wanted to tell it that things would be okay, but just then she felt like her eyes were turning into soft-boiled eggs and that seemed more important.

“Anyway you should be dead,” said the uncertain voice.

“Oh,” said Kim.

“I’m sorry about that I guess.”

“Why would you call to tell me that?” Kim asked. She wondered if her voice was really coming out as slowly as it felt like it was.

“It seemed like the right thing to do,” said the other voice.

“Oh,” said Kim. “Thanks.” She hung up.

At the time she hadn’t thought much about the call because, a moment later, she felt a comfortable little bubble burst in her brain and it distracted her for a long while. Now she remembered it. She looked at the phone on the wall and then she looked down at the body. It still seemed very real, so she went into the living room and looked around.

She was dimly aware that the room looked disgusting. There might have been bugs crawling around in the food on the table. There was a can of computer cleaner with a little straw attachment and a paper bag crumpled up beside it. These things she picked up very deliberately, feeling sure this would help her get a handle on the situation. She shook the can and sprayed it for a long time into the bag and then held the bag over her mouth to breathe in the fumes. She could feel her brain start cooking again and she felt the jittery rush of things start to settle out of her stomach and down into her feet.

It was a very nice day and everything seemed to be just about as it always was. That was good. She looked at the houses. They all looked the same—had the same red stucco tiles on the roofs that made them look like those little straw Japanese hats she saw sometimes in movies. She put her hands on herself. She was wearing the red sweater with the hole over her hip on the left. The hole was very familiar and she looked at it and felt reassured by it. She felt the pen she always kept in her back pocket. It was just as it should have been. That was good too.

Kim headed to Ronnie’s down the street. He was her drug-dealer. Sometimes he was her boyfriend too, but she didn’t like to think of him that way. She was much more comfortable with drug-dealer. It was Ronnie who had tried to clean her up once, six months or so ago. He’d even stopped dealing so he wouldn’t have anything in the house. But when she started up again, so did he. For weeks at a time he would be the only person she talked to, and sometimes he said they were friends, but she knew what they were.

The two Kims had stood there for a moment, each one trying to understand the other; each looking at the other’s face, at the swoop of blonde hair over the other’s forehead and the way the light seemed to nest there like a bird at home, and the black eyes thrust deep into the high cheeks and the little murmur of awe upon the lips. Each had the unique experience of seeing herself for the first time as others had always seen her. Then Kim had felt a rush of overwhelming terror and revulsion. It came out of her stomach and shot upward and, instinctively, she grabbed the heavy iron frying pan from off the stove and swung it at the other Kim’s head so that it sank satisfyingly into the other Kim’s brain.

Ronnie was on the couch when she went in. He was wearing that t-shirt with the two little kittens on it and was stretched out in such a way as to take in the sun that came through the window onto his belly. Seeing him, Kim felt overcome with a kind of free-floating remorse. She wasn’t sure what she felt so sorry about, only that she did feel sorry.

“Kimmy,” Ronnie said, craning his neck to look at her.

She didn’t speak. She felt hot tears welling up in the reservoir behind her eyes and suddenly felt for Ronnie both tenderness and shame.

“You alright?” he asked. He was going through the motions of standing up now. She wanted to tell him not to but she couldn’t speak. Then he was hugging her with his big soft arms and she felt her throat close up. She wanted to shrink, to become so very small that she could escape his grasp, maybe even small enough to disappear. It had been awful looking at herself in the kitchen. How must she have looked now?

“What happened?” he asked.

She pushed him back a bit to face him. She felt her voice start up like the engine to a lawnmower. “I’m having a bad day,” she struggled to say.

“Talk to me,” said Ronnie. “What’s going on?”

She didn’t want to talk to him. She didn’t want to talk to him ever again. This wasn’t the first time she’d felt this way. She never wanted to talk to him. The thing—the unexplainable weirdness—only made the feeling more pronounced.

He nodded, understanding. “I’ll get some,” he said. “Sit down.” He kissed her eye where it was wet and then he headed off. She watched him go and felt a little disgusted by him. He was always so nice to her and, for whatever reason, she could only respond with coldness. He didn’t even make her pay most of the time.

She waited and listened for Ronnie and felt herself vibrating slightly, like the atoms in her body were moving around in a way that might be dangerous. She started to worry she would come apart right there on the spot and she decided, for no reason at all, that she didn’t want to stay. She went back to the door and fished in the little bowl that was always there by the radiator. It was full of loose change and rubber bands and, under all that, she found the keys to Ronnie’s car. She picked up the keys in time to see Ronnie come waddling down the hall toward her. He looked soft and half-asleep in that t-shirt with the three little kittens on it and he smiled a little and waved a plastic bag at her.

“I have to go,” she said gravely.

Ronnie’s car was a rusty orange rib on two temporary spares, but it looked about as it was supposed to look so she got in and started the ignition. She could see her street in the mirror. It was familiar but seemed, somehow, to be closing in behind her, so she drove faster through the intersection. At the light she saw the wreck of a car. It was a burnt out metal rind crawling with gears and springs from the seating, like the remnant guts of some kind of synthetic life now fled. As she looked, there came a sudden, awful scream of metal on metal and she felt herself tossed around side to side. When she opened her eyes a moment later, though, there was nothing. Just the road ahead of her.

She turned on the radio and made it loud enough so that she wouldn’t be able to hear herself think. Power lines traced the road overhead and Kim let her eyes follow them drowsily. It was dark and the lines were vaguely illuminated by the orange street lamps, foggy bubbles of rust-colored light in which she could see a haze of summer insects. When she was a teenager, she used to go for long drives with her friends that lasted hours and promised no destination. They would smoke and laugh and feel important in that way young people have of feeling important. It felt good and the time never seemed too late until one of them would suggest they turn around and then they’d feel a kind of grief rising in them with the gray dawn.

She went to the diner where she liked to eat lunch sometimes. The windows were frosted with the irregular fringes of precipitate morning and she could see her own reflection warped and misconstrued in the glass partition beside her. It was still early so there were only a few others there. The waitress leaned against the counter typing something into her phone. When the door shut, a little bell rang and everyone in the place looked to see who it was.

She wasn’t surprised to see her there, alone and waiting at the booth in the corner, but she wasn’t prepared for it either. She looked at her—at the other Kim and felt an immeasurable, unprecedented despairing compassion come over her that was somehow coupled with a kind of condescending hatred for the pathetic little, worn-out figure she saw. The other Kim noticed her and raised her hand a bit and Kim walked over.

“Hi,” said Kim.

“Hi,” Kim said.

They watched each other. Kim didn’t like the look of the other Kim. She was somehow much smaller than she thought she should have been and her sweater with the little hole on her right hip looked terrible, like the coat of a dog in from the rain. She’d always felt all wrong—like she didn’t fit. Now she could see what that looked like and she didn’t like it. The other Kim didn’t seem very pleased by what she saw either.

“I guess it’s my turn to tell you what’s going on,” said the other Kim.

Kim nodded meekly.

“I’m not sure I can.”

“Please,” said Kim. The way she said it was really pitiful.

The other Kim started to explain. She did so haltingly, struggling to communicate something that didn’t seem communicable. “Do you…” she started, “If I say…” It didn’t seem right. She settled herself. “I’m going to talk to you like you understand this. If you don’t then just say so but I already know you don’t.”

“How do you know that?”

“Well,” the other Kim made a little reciprocal gesture with her hand.

“Oh,” said Kim.

“So if you have a long list of random numbers, an infinitely long list, eventually some of those numbers repeat, right?”

“Right,” said Kim. She didn’t seem confident in her answer.

“Well I guess everything is like that.”

“Everything?”

“Like outer space and time and all that. Realities.”

“Oh.”

“Right. So if it’s infinitely long…I guess stuff repeats.”

“Like people?”

“Like people. Like…everything.”

“What would that be like?”

“Like this.”

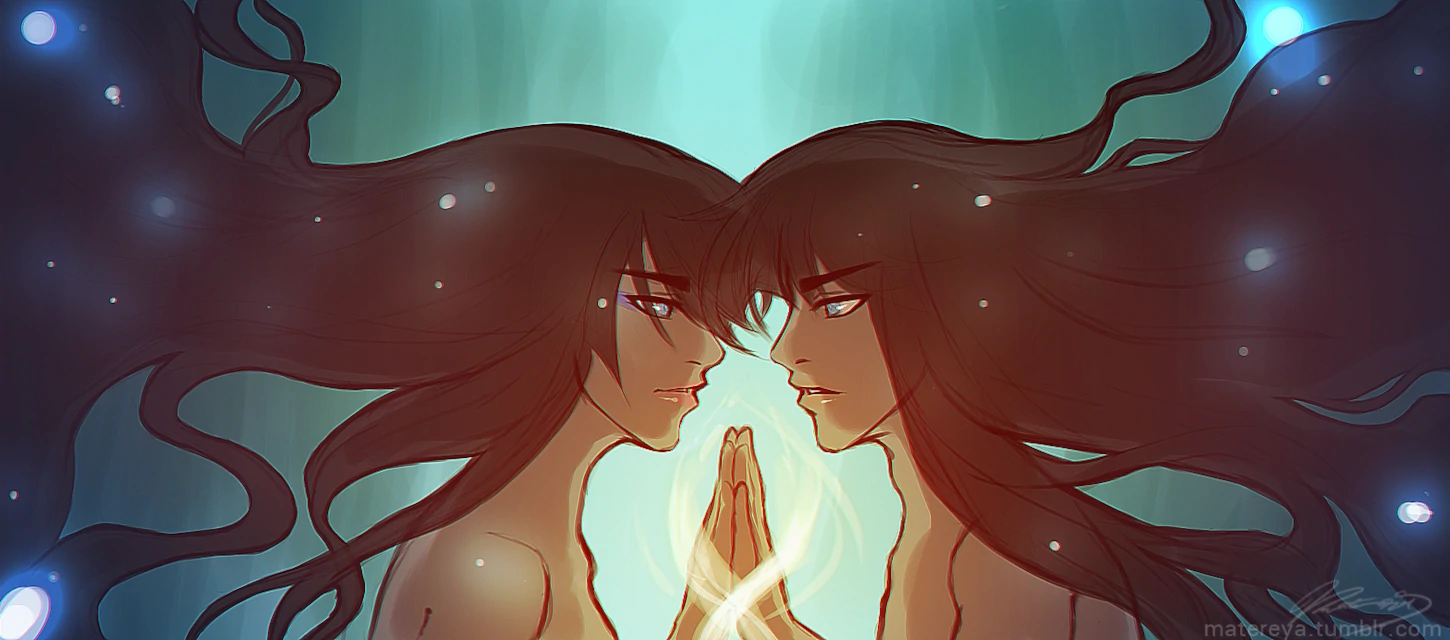

“I don’t understand this at all.” Kim’s eyes were very black and the other Kim suspected that if she could look behind them she’d see little aerosol bubbles still bursting. The other Kim pulled the napkin out from under the knife and fork and said, “Give me your pen.”

Kim reached into her pocket and produced the pen and handed it over. The other Kim started to write on the napkin. She wrote her name over and over again in neat cursive lines. Kim recoiled a little at seeing her own handwriting. Then the other Kim turned the napkin and started writing again so that the new lines intersected with the first, crosswise. She did this until the napkin was nearly black with ink and scrawl. Then she slid it across the table and put the pen in her own pocket.

“What’s this?” asked Kim.

“It’s called a palim…palmpiset? Palma…” The other Kim was struggling with the word in her mouth. It was an uncomfortable word and she didn’t know it very well. “Palimpsest,” she said. She looked pleased with herself. “Anyway, that’s what’s happening. The napkin’s getting full up with Kims.”

“What happens when it’s full?”

“Oh,” said the other Kim. She said it excitedly, like a girl in class, glad to know the answer.

“Oh,” she said. “It’s um…convergence.”

“What’s that?”

“When the napkin’s all black.”

“I don’t understand.”

“It just repeats until it’s all just one thing.”

“What?”

“I think things will just repeat with little differences until everything becomes one thing.”

“Because the universes are…are converging?”

“The realities. It’s all in the same universe. But yes. I think so. At least that’s what the other one told me.”

“Who told you?”

“The last time I had this conversation, I was the one asking the questions.”

“Oh,” said Kim.

They got quiet. They didn’t want to look at each other anymore so they just looked at the sun outside the window, at the way it made all the sky white and creamy.

Kim grabbed the napkin then and brought it to her eyes. She was crying.

“What’s wrong?” asked the other Kim.

“You already know, don’t you?”

“Yes,” said the other Kim “but it seemed like the right thing to say.”

“You’re not even high.”

“I’ve been sitting here a while I think.”

“Are we different?” Kim asked hopefully.

“I’m not sure,” said the other Kim, considering the question. “I think we might be at different times in the same place.”

“I don’t like this,” said Kim, sniffling.

“That’s not why you’re upset though,” said the other Kim.

“No,” said Kim.

“You wish I was better.”

Kim nodded her head.

“I wish I was better too,” said the other Kim. “I wonder if there’s a Kim who’s better out there.”

“There could be. Eventually. Couldn’t there?”

“Maybe if things repeat enough with those little changes. I’m sorry I guess.”

“Because you aren’t better?”

The other Kim nodded.

“Me too.”

“That thing that happened. Will it happen to me?”

“Does it matter? If our lives are all the same?”

“It’s still mine,” said the other Kim.

“Yeah.”

Kim tried to think of her whole life and it was not an easy thing to do. She tried to visualize it as a strip of film with all the moments of her life in little frames all unspooled before her. It was overwhelming and made her feel like she was going to cry again.

The other Kim spoke up. “Listen” she said, “I don’t want to talk to you anymore. I’m going to leave. But you stay here a while. I think it helps if you relax.”

Kim nodded through her soft tears. She wanted to leave too. She always wanted to leave.

“Goodbye,” said Kim.

“Goodbye,” Kim said, “can I have your coffee?”

“I guess.”

Kim reached out. The coffee in the cup had gotten cold and when she took a sip, it went down like wet cement, and she spilled a little on the table. She reached out for a napkin and found a stack of them. They were all soggy with tears and black with writing. Her name, again and again, Kim.

The other Kim stood at the door, looking back at herself. She wished she hadn’t spent so long in the diner because it was hard to think straight now that she’d sobered up. She would need something to get her head right. She went out to the car, started it, and pulled out of the lot.

The day was murky and wet. There was fog all over and the sky was a gray film full of diffuse sunlight. She came to an intersection and waited for the light to turn. She saw the stars reflecting on the dashboard through the glass and it distracted her for a moment, and when she looked up she saw Ronnie’s car coming toward her down the road.

Suddenly it felt like the world had cracked open and she was tumbling over and over again sideways in the car. She could see the road and the earth spinning around outside the windshield and felt the thud of metal slamming into her bones. There was an awful screeching sound in her ears and she felt she might be screaming out but she wasn’t sure. It was like she was in the gut of some animal rolling over and dying and making a big fuss about it.

She felt her breath come quickly, irregularly, and waited for it to slow down. When it did, she looked at her hands. They were still on the steering wheel. She was worried they might not let go, but she told them to and they did as instructed. That was good. They were her hands after all. She fell out of the car and looked around. There was nobody else on the foggy road.

Her legs felt very heavy and slow as she passed Ronnie’s house. She was as tired as she’d ever been and she thought about going in to get her head full of something to take the edge off but, looking at the house with the green stucco roof like a Japanese hat, and the car like a rusted orange rib, she felt suddenly very sick and very ashamed of herself and decided to go in for a different reason. She wanted to be around Ronnie. She wanted to talk to him. This was unusual.

The house was dark so she called out his name. After a minute she heard his voice from upstairs. “I’ll be down in a minute,” he said.

She stood there in the dark wanting to be near Ronnie, wanting to be near anybody. But, as she waited, she remembered what her face had looked like across the table in the diner and a different feeling crept in to replace the good one. She went to the couch and picked up the phone from the floor where Ronnie kept it. She dialed her own number, hoping no one would answer. Eventually, though, she heard a voice on the other end of the line.

“Hello,” it said. It was definitely Kim’s voice but it was slurring and sounded like it was coming in from far away.

“Um…” she felt the air slip out of her and thought she would cry or scream. “Hello,” she said. “I’m calling you from…” it dawned on her that she was talking to someone who should, at that moment be dead on the floor. “Are you…” she wasn’t quite sure how to put it nicely, “alright?” She heard the voice on the other end of the line murmuring in search of an answer. This conversation was familiar somehow. “I didn’t think you would pick up,” she said.

“I did pick up,” the other voice said.

Kim tried to sound certain. It seemed very important to get through to the other Kim and explain things but as she spoke, all the conviction drained from her voice. “I’m calling because I think I killed you.” She thought about what the Kim in the diner had said and continued, “Or maybe I haven’t yet. Maybe I’m in the future.” She waited but the other Kim didn’t answer. “Anyway you should be dead,” Kim announced.

“Oh,” said the other Kim.

“I’m sorry about that I guess.” That seemed the wrong thing to say to someone you’d killed.

“Why would you call to tell me that?” said the other voice.

“It seemed like the right thing to do,” Kim answered.

“Oh,” said the other Kim. “Thanks.” She hung up.

Kim felt very alone then but when she heard Ronnie stirring upstairs she got up and ran to leave. She thought of what her own face had looked like and didn’t want to be seen by anybody ever again.

She opened the door to her own house very carefully and slowly and called out. “Hello,” she said. “I hope you’re not holding any pots and pans.” Nobody answered. She looked around, relieved to find nobody there. The house was as she’d left it and she was glad she had cleaned the place up before going out.

Tentatively she went to the kitchen and turned on the light. She winced, expecting to see the body on the floor but was happy to discover that it was gone. Or maybe it was never there, she thought. That was possible too. In the living room, she climbed onto the wheezing couch and hugged her knees close to her chest. She felt like a little girl and thought about herself as a child. She tried to imagine what it would be like if things had gone differently. She wondered if it was true what the other Kim had said—about tiny changes. Maybe there was a better Kim out there, she thought, or maybe there could be, but she couldn’t imagine what she’d be like. She closed her eyes and tried to imagine something else: she imagined what it would be like not to exist at all. It was less than death; it was nothing, the real meaning of the word. It wasn’t cold or empty because it didn’t have any feeling or aspect whatsoever. It felt right. It felt reassuring.

She stood up then and turned around and went inside. She closed the door behind her and made her way to the kitchen but stopped suddenly. The two Kims stood face to face. Looking at her, Kim felt all that awful sorrowful nothingness come creeping over her and she tried to open her mouth to speak.

But Kim picked up the heavy iron frying pan from the stove and swung it hard so that it sank satisfyingly into the other Kim’s brain. As the body slumped to the ground, Kim watched it and experienced a kind of confused horror. It was Kim and Kim had killed it. Kim had killed herself. Panicking, she felt a jittery rush shoot up from her feet and into her stomach. She looked down at the body and didn’t understand. Kim killed herself. She thought about that—the implications of it—and knew there was a saying to describe what she felt. It took her a moment to remember what it was. When she did, it struck her as strange—both more alien and more starkly literal than it had ever felt before. The saying was this: she couldn’t wrap her head around it. She stood there, in the kitchen, looking down at her own body on the floor and felt her head try to wrap itself around a fact that was too big and too shapeless to be surrounded.

She was afraid if she touched the body—the body that was certainly her own—something bad would happen so she just looked at it. She was still holding the heavy iron frying pan she’d used and she lifted it to have a look. There was a black smear on one side that she knew was blood and she was tempted to taste it to be sure but decided against it. She was pretty sure the frying pan was real, which meant the blood was real which meant, in turn, the body on the floor was probably real too. That meant Kim had killed herself. She thought about that. She thought about it a long time but she never could wrap her head around it.