Stop the car, Tulika thought to herself, but in her silence, Rajdeep drove on.

“Stop the car,” she said, out loud at the next turn, and Rajdeep drove on. She felt sick: a dizziness in her head and a painful jolt in her stomach. She needed to throw up.

The girl on Tulika’s lap seemed unaffected by Rajdeep’s reckless speeding, unbothered by the rise in altitude. In four years, their daughter had never seen the world outside of the city, yet she didn’t blink at the blind spots as the Toyota zipped around the bend; she showed no fear of the deepening valleys of the Himalayan Mountains. Tulika pulled out an AirMask from the tank under her seat and offered it to her daughter. The girl refused.

Around another sharp bend, Rajdeep sped up to overtake a car in front of them. Tulika wrapped her arms around the girl and clutched her tight.

“Stop the car,” Tulika said, gulping.

“What happened?”

“She’ll get sick.”

Rajdeep turned to Tulika. His eyes were opaque and his eyelids always drooped a little too low for Tulika to read him. When he glanced down at the girl, Tulika wondered if he had hesitated, if he had lingered a little too long.

“She’s fine,” he said. “She’s always fine.”

“No, Raju. I’ll be sick.”

Rajdeep groaned and pressed his hands around the wheel. He always held the steering wheel too tight, like he was squeezing and choking it, until his hands began to sweat, until the leather upholstery left red marks of strain on his palms. He had large, powerful hands. He used to grab her wrist playfully, she remembered, and yank too hard, hurting her.

He slowed the car at the next large clearing by the roadside.

“Go,” he commanded.

Tulika unclamped the seatbelt. With the girl still cradled in her arms, she stepped outside.

The pahadi morning air. It came to her first as a memory of past breaths; it had been a half dozen years since she had travelled to such heights. The air was light, thin, almost completely scentless, without the heavy weight of lead and smoke characteristic of Faridabad. Tulika looked down at the girl for her reaction, but her expression—passive and uninterested behind those large, brown eyes—did not change.

It was quieter, too, almost silent. There was little rush of traffic now and no panic of the WarConch to halt them from moving ahead. There was a crackle of branches echoing from the forest below, a sigh from the girl in her arms, the slamming of the car’s door as Rajdeep stepped out behind them.

But then that sickly feeling in her stomach returned, that weight in her throat, that spinning whirlpool of pain in her head. Tulika rushed to the side of the road and peeked down from the low concrete barrier at the welcoming depth of the mountain, the infinite canyon which ended with the plains far below. Closer up to her, just below the barrier, were brown shrubs and green grass and a khud-full of plastic food wrappers. Tulika moved the girl from her front to her side, now holding her between her hand and her left shoulder. The girl put her arms around Tulika’s neck to shift her weight and find balance.

But the girl’s face was too close. Her legs dangled over Tulika’s stomach when Tulika bent lower over the concrete. She shifted the girl’s weight from one shoulder to another, and looking around without another option, decided to sit her down on the slim breadth of the barrier.

“Let me hold her,” Rajdeep called out from behind them.

Tulika froze. She remembered the girl’s hat. She had left the hat in the car.

Rajdeep’s eyes had now risen up to unaccustomed attention. He rushed closer to them.

Before the trip, Tulika had bought a new green fedora to cover the girl’s head. The fedora’s wide brim fit over the girl’s stretched, oblong skull. But the hat was inside the car, and the girl was out here, her head on full display.

Rajdeep walked over and grabbed the girl from Tulika. Immediately, Tulika turned back to face the mountain, opened her mouth wide, and vomited—boiled egg and soggy pieces of bread and cucumber. She held her hair back and let it all belch out. Her head buzzed.

She paused for a breath, looking up in front of her at the fog, at the sunlight streaming through the clouds above, the hazy valley on the horizon. Behind her, she could hear the hush of the mountains. A light wind. A crackle on the branches. Nothing from Rajdeep. Nothing from the girl.

When she finally turned, she saw that Rajdeep was holding the girl up in front of him, one hand cupping her below her little legs, the other hand wrapped around her waist. His bearded face—with the feral musk of sweat she loved, the same face she once rubbed against until it chafed her own cheeks—seemed foreign and unfamiliar so close to their daughter. In nearly four years, it was the first time he had held her.

And yet, he had grabbed her like he grabbed the steering wheel: with a cold exertion of strength. The girl was casually swinging her legs now, kicking her white tennis shoes against her father’s chest.

Tulika wiped the brim of her mouth with her sleeve. “Put her down, Raju,” she said.

He loosened his grip.

“She will stand by herself, Rajdeep. Put her down.”

Rajdeep lowered her on her feet and backed away. Tulika ran up to the girl and clutched her hand.

“Are you okay?” Rajdeep’s voice was low and raspy, familiar again for Tulika. Now at a safe distance from the girl, he looked at the oval egg of her head with renewed fascination. Tulika knew that expression. A little curious, a little afraid.

“I’m fine, Papa,” the girl answered with a nod.

“I’m fine,” Tulika answered with a deep breath.

The girl then pulled on Tulika’s arm and pointed at her sneakers: the laces on both her shoes had come untied. Tulika crouched down on one knee.

“Watch,” Tulika said. “Lift both, say lift both. Cross over, say cross over. Watch.” She pulled both ends down. “Blue bunny ears, blue bunny, then into the gap, into the gap. And done. Now do it over the other foot.”

The girl shook her head. “You do it,” she commanded.

Tulika sighed. “Look again.” She repeated the entire exercise on the other shoe.

“Let’s go now,” Rajdeep ordered.

He must be hungry. Tulika worried she was wasting their time. She got back in the car with the girl and strapped on the seatbelt. Tulika found the girl’s fedora and placed it over her head. Rajdeep looked at both of them one more time with the same hollow expression in his eyes and started the car.

She had seen that expression before. There she was, half conscious under a heavy dose of morphine, stitches binding the incisions in her abdomen, needles plunged into her veins, and tubes drip-drip-dripping behind her bed.

Your daughter. She could hear a woman’s voice. Your daughter.

Tulika awoke on the surgery bed, under a glaring light that revealed the life below her. She remembered the frantic voices from her subconscious. There, there. The shape. Placenta. More oxygen, nurse! The head. She remembered the pain. The screeches.

“Is she…?” Tulika murmured to the blurs in the room.

“Your daughter is fine, Mrs. Sinha,” came the woman’s voice again. Firm and comforting. Dr Joshi. “We had complications, but it’s all fine now. Do you want to hold her?”

A pair of blurry hands carried the baby and Tulika found herself reaching out to grab her, to hold her. Her daughter. She found herself instantly comfortable with the first touch. She knew where to put her arm below the baby’s body. The girl was wrapped inside a clean, white cotton sheet. Tulika wrapped the cloth shut over the baby’s chest when she felt a slight waft of air in the room. She let the girl’s little toes peek out from below. She flicked her finger against the sole of her naked feet and felt the girl shudder with a soft, irritated moan. The girl turned her head into the warm pocket of Tulika’s breast, right over her heart.

Her head.

Tulika took a deep breath and finally let her eyes wander over the girl’s head. She had Rajdeep’s eyes, larger in proportion to the rest of her face, and her eyelids drooped low in lazy reluctance to open up to the world. She had Tulika’s nose, small and flat. Like a porky piggy, Rajdeep had joked when he met Tulika for the first time. The girl’s skin was creamy brown, like Tulika, but a much lighter shade, like Rajdeep looked on the one day of the month he shaved his beard.

But that’s where the similarities stopped. Her skull was nothing like Tulika had ever seen before. It was an oval, elongated strangely on the sides of her head, a smooth egg lying horizontally over the girl’s neck. Tulika remembered the ultrasounds clearly now. She had seen this. This shape. This head. A vessel much larger than the brain it carried.

“Raju…” Tulika muttered.

Dr. Joshi’s frame became clearer. She was standing in a white coat at the foot of Tulika’s bed, a facemask hanging low underneath her chin, a smile on her face. “Your husband is outside Mrs. Sinha. We can let him in when you’re ready.”

“Raju…”

She saw Rajdeep walk in the door. In his large hands, he carried a small soft toy, a blue bunny rabbit he had bought for the baby before Tulika went into labor. His bearded cheeks lifted when he smiled.

Tulika shifted the baby between both of her nestling arms and held her up. The cloth unraveled to reveal her head.

Tulika watched his eyes. The sparkle made way for shock. Rajdeep looked a little curious, a little afraid. He took a step backward, away from Tulika’s bed, back toward the door.

This was their child, both of theirs, and all of her own. Tulika wanted the girl to cry more—shouldn’t babies cry more?—but instead, she felt her own eyes well up. Somewhere in the background, she could hear Dr. Joshi’s voice: 2:43 p.m., 2.8 kgs, we’ve taken a blood sample, first feeding…

Dr. Joshi was at the foot of Tulika’s bed, now clicking a pen in her hand, cradling a clipboard. “Do you have a name for the baby?”

Tulika brought the girl back into her full embrace, close to her heart. And when she turned to Rajdeep, she saw him standing uneasily by the door, jittering his feet. He squeezed the blue bunny with his large fingers until its cotton head disappeared completely inside his hand.

Within a year of the girl’s birth, the manufacturers in Shenzhen cut trade ties with Rajdeep. War broke out with China over Arunachal Pradesh and with Pakistan over water, or with Pakistan over Kashmir and China over air regulations, or both, Tulika couldn’t remember. Rajdeep was slower to react than his competitors, who had found new sources in Indonesia and Vietnam. When Supremo Bikes called him to ask about new imports of motorcycle parts, he had nothing to report anymore. Instead, he went on the road, back on search. New clients, new suppliers. “Same business, Tulika,” he said. “There are many, many fish in the ocean.”

She held the girl in her arms, but kept her skull sheltered from him under a robe. “Same fish?”

“Smaller fish.”

He turned away. He never looked directly at the girl, never spoke to her, or spoke of her, or ever came close to any physical contact.

Is that how they were now, these fathers? When the Chawlas next door invited Tulika for their son’s sixth birthday party, she sat with the girl alone in a corner of their dining room, eating eggless white cake and watching the fathers. Some were close to their children, holding up the girls’ hands as they balanced on their feet, allowing the boys to straddle behind their shoulders like backpacks. Some fathers reminded Tulika of her Papa in Jaipur, who left the children alone with the mothers for most of the evening, but came back to check up on a regular basis and give the kids a scruffy kiss on the cheek before returning to the company of other men.

Rajdeep didn’t come to the party and Tulika was comfortable without his presence around the girl. She didn’t ask him to be the father who carried children in his arms, or even be like Papa, who drifted in and out of her life as his whims commanded. Instead, she compartmentalized parental obligations like the rest of the young mothers in the neighborhood had after the wars began. Home for the mothers and road for the fathers. When she got pregnant and Rajdeep asked her to quit her job with Tooni Graphics, Tulika did what her own mother had done at her birth: she quit.

The girl was her duty now. Home for the mothers.

When they first brought the girl home from the hospital, Tulika slept with her in the bedroom and Rajdeep took the sofa in the living room. They lived in his flat in Faridabad’s Sector-87, where there were two more bedrooms, one each for Mummyji, Rajdeep’s mother, and Gitu, his sister. The three women raised the baby together. They patted her on the back to make her cough, sang old bhajans to soothe her crying, and opened their arms wide to let the girl crawl up to them. They pressed down the hair over her skull to cover the shape and celebrated when the girl jiggled in recognition of the music from Mummyji’s television.

Rajdeep stayed away, avoiding the girl as she grew up, keeping out of her path as she wheeled around the house on her plastic walker toy. But when the girl closed her eyes, rolled inside the safety of her blankets, or pressed against Tulika’s breast, Tulika saw Rajdeep study her carefully from his peripheries, watching her skull continue to grow sideways with morbid fascination. Tulika watched it, too, but what was one shape from the other for the child, she thought? When the head stretched longer, Tulika bought her a wider hat.

Before the girl turned one, Gitu died of lung cancer. Mummyji was diagnosed soon after.

“Those new AirMasks, Raju,” said Tulika, “I saw them in the mall.”

“Made in China,” Rajdeep coughed.

“We need them, Raju. Gitu’s gone, Mummyji has the disease, and the girl…”

“She will be fine, Tulika.”

“Raju, please.”

So he drove down to the mall and returned with oxygen filters, tanks, and AirMasks. He set up the filters around the house and installed the O-Tanks in their Toyota. But he warned Tulika about overusing them with the girl. “She’ll become too sensitive, okay? She needs to breathe real air and make her lungs stronger.”

Tulika waited for Rajdeep to leave home before she forced the mask on the girl. “Go now. Breathe normally. Normally.” The girl shook her head and scampered away to the open windows, to the door outside, to the air that was killing them.

Tulika and Mummyji coughed all night, and Tulika worried that their sleeplessness was keeping the girl awake. But the girl slept through it all. She inhaled deeply on the smoggiest winter nights in Faridabad and cried for Tulika in the mornings without losing a breath.

“This is not the first case. As a matter of fact, if our tests are correct, your daughter is one of the first few ‘Proto-Forward’ babies.”

Tulika trusted Dr. Joshi, who owned a small, private clinic and treated both the pregnant mother and the perplexing child. Tulika had returned to see the doctor every three months since the girl’s birth, taking brain scans, blood tests, lung exams, urine tests, and cognitive development analyses. The results were always the same. Your daughter is normal, she would say. But when Dr. Joshi called them in to share international news about the girl’s condition, Tulika insisted that Rajdeep come along too.

The doctor’s office was comforting to Tulika, with its bright, lime-green curtains and walls adorned with photographs of smiling babies and their proud parents. Among those photographs was Dr. Joshi’s own, with her own husband, a tall, darker-skinned man in a fishing hat and a baby in his arms. She leaned next to him in a T-shirt and shorts. Both of them smiled widely on a wooden plank somewhere with blue seas behind them.

How did she manage this, then? In this time of war, with her job and that baby and that holiday with the family crammed closely into the frame of a small photograph? Tulika hadn’t left Faridabad since the pregnancy, since she had quit her job. She could work from home, she had thought; she could design on her own computer. Once, she had even offered to help Dr. Joshi with a logo for her clinic, but then the girl had begun to cry, and Mummyji needed her to call the cable company, and Tulika’s computer caught some malware, and she never got started.

She knew she would go back to it one day. One day, yes, when the girl was old enough. When she could leave her with Mummyji. The clinic could use a logo. Something nurturing, a seed blooming into a flower. Tall trees. The nurturing shade of a green forest? Or a more literal representation? A stethoscope around a baby. A baby crawling to her mother. A mother petting a child’s head? A father pressing a child’s skull.

“Proto-forward babies?” Tulika asked.

She was sitting between the girl and Rajdeep, who was silent, listening with his head bowed low

“Yes, that’s it,” Dr. Joshi answered. “There was a boy out in Peru, born about five years ago. He had your daughter’s condition. And he is growing up with no problems. Then three more in China, out of which two survived. Both are healthy, normal, children.”

“What happened to the other Chinese child?”

“That was—what can I say?” She waved her hand with easy dismissal. “Just an unfortunate family accident. You know, family problems? Nothing to do with the condition.”

“But I searched online about this. Cranio Synth To…”

“Craniosynostosis. No, no, your baby doesn’t have that. Let me explain.”

Dr. Joshi flipped open her prescription notepad, and with a black pen, drew two oval shapes, vertically and horizontally, in jagged, uneven strokes. “The first,” she explained, “where the head is long to the back, that is Sagittal Craniosynostosis. Only dangerous in rare cases. But this,” she pointed to the other oval, “where the skull is long side to side. That is your daughter.” She clicked her pen down and let it drop on the notepad. Now Dr. Joshi’s voice sped up as she spoke. “It really is exciting news. Scientists in America are calling it a natural evolution. A reaction to the environmental changes.”

Tulika didn’t understand, but the girl was healthy, wasn’t she? That was all that mattered, wasn’t it? She turned to see Rajdeep’s reaction, but he was distracted, staring at his phone.

Later that afternoon, they were in the Toyota, about to drive back home, when the WarConch began to blow out from the street speakers. Tulika hoisted the girl into her arms and all three of them rushed back up to Dr. Joshi’s clinic. From the third-floor window, they saw hundreds of people leave their vehicles on the street to rush indoors: into coffee shops, O-Bars, and down to the metro station. The WarConch continued, its one high note urgently trumpeting out of every Public Announcement speaker and mobile phone in the vicinity until there was no one outdoors anymore. Tulika crouched to the ground on all fours and pulled the girl down beside her. Rajdeep and the rest of the patients and doctors around them did the same.

The conch kept blowing with merciless consistency, the same loud blare without a flinch or change in tone, for five minutes.

And then it stopped.

“Just a drill,” Rajdeep muttered. “Let’s go home.”

The girl had her own room now, Gitu’s old room, which Tulika had decorated with an array of different soft-toy critter creatures—squirrels and bears and rabbits—in pink and blue. During the day, the girl sat on the carpet playing with plastic building blocks; at night, Tulika tucked her into bed and slept on the floor next to her. Rajdeep—when he was home—drank whiskey alone and camped out on the living room couch.

When she was eleven months old and rolling around on the carpet next to Tulika one afternoon, the girl said “Pa, Pa-Pa.” “Muh-uhm” came a few days later. On her first birthday, Rajdeep scheduled his final trip to Shenzhen. On her second birthday, he found suppliers for new manufacturers of chain sprockets in Ranchi and took the day-long train journey for the meeting. When the girl turned three, the Haryana Small and Medium Enterprises Association organized a convention in Panipat; Tulika didn’t throw a party for the girl and the girl didn’t ask for Papa.

Rajdeep was back home by the time the girl began to emulate Tulika. In front of the mirror, under the yellow light of the sun slanting into the bathroom through glass-paneled windows, Tulika and the girl wet their toothbrushes with a few careful drops from the mug and brushed in parallel: Tulika leaned sideways against the tiled wall and moved in monotone angles over her teeth; the girl swayed in front of her, dancing to faint sounds of music from the television in Mummyji’s room.

On one of those mornings, the girl accidentally swayed into the mug. It tumbled from the washbasin, spilling onto the bathroom floor. Rajdeep heard the thud and hurried into the bathroom. A thin stream of water snaked its way from the girl, bypassed Tulika, and meandered in Rajdeep’s direction. Tulika froze against the wall, holding the toothbrush inside her frothy mouth. Rajdeep pointed a finger at the girl’s oval head but looked to Tulika instead. You, he said with his eyes.

He slammed the door shut behind him, causing a crash that stirred a bar of soap off its dish and made Tulika flinch. The girl spat paste and froth into the basin and wiped her mouth clean.

The trip to Shimla was Tulika’s idea. The girl was old enough to start kindergarten, and Tulika convinced Rajdeep that they needed a holiday—just the three of them—before school began. It was scheduled to be the hottest summer in North India ever recorded, hotter even than the last year when Mrs. Chawla’s son from next door threw an egg on Sector-87’s driveway to watch it sizzle. The mountains would be cooler, she had said. It was where she and Rajdeep had spent their honeymoon, before the wars, before the girl.

But as soon as Rajdeep drove the Toyota out onto the highway, Tulika felt that she had left something behind. They had extra sweaters, phone chargers, AirMasks, and O-Tanks. They had building blocks for the girl and her second pair of sneakers. What was left?

She couldn’t figure it out, and she remained unsatisfied, unsettled. The headache and the altitude sickness distracted her on the drive up, but soon after she vomited, the worry consumed her again.

He had held her, she thought. For the first time, he had held her. Rajdeep listened to the radio and drove fast around the blind corners. Tulika looked out the window in silence. She needed to know. What did she forget? They were going to be alone, together. Just her and the girl and him. Why were they going?

For lunch, they stopped at Sunny’s Full Stop in Kandaghat, the dhaba where—almost six years ago—Tulika’s wedding ring had slipped off her buttery finger while she ate aloo-paratha for lunch. Unaccustomed to bearing a heavier weight, Tulika didn’t raise an alarm until they had already driven an hour further. Then she screamed and cried and apologized, and Rajdeep, laughing in a way he never laughed anymore, drove her back to Sunny’s to find the ring. That night Tulika and Rajdeep had finished a bottle of whiskey in celebration and didn’t leave their hotel room. “Don’t worry,” he had slurred. “This will be a very funny story for the future. The funniest.”

She was more accustomed to the weight of the ring on her finger now, and back at Sunny’s Full Stop, that incident seemed like an anecdote from someone else’s life; a scene from a TV serial where every marriage problem was resolved with comedy and nobody went for their monthly lung scans. The parathas didn’t taste as good as they used to, either, and Rajdeep kept complaining as he licked achar off his thumbs.

“Do you want something else?” Tulika asked. She always knew when he was unsatisfied. There was a restlessness to his motion: below the table, where he was sitting with one leg crossed over the other, she could feel him jittering his foot side to side. The jittering had gotten worse lately, more impatient, as if he was in constant need of escape. From the inside breast pocket of his jacket, he reached for his steel silver flask of whiskey and took a sip.

“Something else?” Rajdeep repeated. “We have spent a hundred and forty each on our parathas, ninety-five on her egg thing, and we still need to save for the petrol pump. How much do you think…?”

He stopped himself from finishing the sentence. His foot shook faster, more violently now. Tulika was sitting beside the girl, both of them opposite Rajdeep at the table. The girl wore the green hat over her head and ate her parathas without complaint. Below the table, Tulika saw that the girl was swinging her tennis shoes, marching one leg after another in the empty air. When her feet came precariously close to kicking against Rajdeep, Tulika placed a hand on the girl’s knee to make her stop.

The girl looked up questioningly, and in the sudden movement, the fedora flew off her head.

Rajdeep stopped moving. Tulika scrambled to fix the hat back over her skull. Had anyone seen it? Tulika shot a glance around their table. The staff was by the cashier’s table and there was no one else in the dhaba. Rajdeep shifted his seat back from the table in an instinctive reaction. Tulika needed him to calm down. She needed order. Just breathe, one, two breaths.

“Relax, Raju,” Tulika suggested in a softer voice. “Do you want one more paratha?”

“One more paratha?” Rajdeep shook his head and sighed. “You don’t understand anything. Those days of Supremo Bikes are gone, okay? We can barely afford to keep spending on O-Tanks for her. Should I really repeat how much we have spent today?”

“Don’t get angry Rajdeep, I’m just offering…”

“I’m not angry, okay? I’m just talking louder.” Rajdeep leaned away from the table and grunted. He swirled open the top of his flask and took another sip. “I’m not angry.”

“Yes, you are. Be calm, Rajdeep.”

“I am calm,” he slammed a heavy hand on the table, making it wobble under his strength. Then he corrected himself, his voice suddenly becoming mellow and soft. “Okay, not right now, Tulika,” Rajdeep turned the pointy angle of his nose at the girl. He lowered his voice to a conspiratorial whisper. “Not in front of her.”

In silence, they waited for the girl to finish eating. Tulika wiped off crumbs that had dropped down the girl’s chin and Rajdeep sipped from his flask. Before he was ready to go, Rajdeep purchased another bottle of whiskey from the theka next door.

They had enough in the O-Tank for the holiday, but as she waited alone with the girl, Tulika wondered if Rajdeep was right, if they truly had been spending too much on the girl. He was old-fashioned and believed people would adjust, that their bodies would become immune, that even the poison in the atmosphere would eventually become breathable. No, no, he was wrong. He had to be wrong. What about Mummyji? What about Gitu? They couldn’t simply surrender their lungs this way, no, no. She would fight. If the O-Tanks were expensive, she would go back to work. She could design again, maybe, just like before the marriage. What could he even say? Anything for the girl.

Unless…unless he wanted her to get sick. Like Gitu and Mummyji. Did he want her to get sick? Was that his plan? Tulika saw him return from the theka with a black plastic bag carrying more whiskey, and she was sure that she saw him trip over his feet as he motioned for her to get back into the car. He took the driver’s seat and she and the girl went around from the other side of the Toyota to sit beside him. In the pungent odor of his beard and the whiskey, she again wondered about what she had forgotten, why they were out here together.

It had been her idea, all of this. Tulika reached for the AirMask and forced it over the girl’s face, and it seemed that the girl protested a little bit, but Tulika kept it on until the girl began to breathe more peacefully. Breathe, just breathe.

Tulika walked into the hotel room carrying the girl and one O-Tank. Rajdeep, who had stumbled drunkenly up the stairs, followed behind her with the rest of their luggage.

It was what the small hotel called a Deluxe Two-Person Room. Tulika remembered jokes with Rajdeep from their past, of rooms sounding more lavish than they actually looked, of a double bed only large enough for one-and-a-half people—or just one person, your mother, Tulika had once said—of bathrooms with no space for a bath, of that ever-numbing smell of mold. This was a room like that, Tulika thought, their Deluxe Room, where Tulika and Rajdeep would have no other place to roll up to, so they simply rolled on each other.

But now, with the girl in her arms, the same space felt more claustrophobic than cozy. The girl was a wedge between them, a sharp piece of plastic building block that had no fit. The mold made Tulika feel sick in her head again, dizzy and desperate for another long breath from the O-Tank. Rajdeep fished out the new bottle of whiskey and began to pour it carefully into the mouth of the flask. The sound of the gushing liquid made Tulika feel thirsty, too.

The girl had seen the playground behind the hotel from the window and was suddenly desperate to ride the swings. “I’m going out now, Mumma,” she said, and Tulika knew by her affirmative voice that her mind was made up. Tulika wanted to leave with her, leave the congestion, step into the air outside. She grabbed the girl’s hand and nodded.

Rajdeep closed the flask top and rose quickly to his feet. “I’ll come, too.”

In the yellow tinge of late afternoon sun, the tiny playground was filled with a dozen children, laughing and screaming, jumping and falling. Two of them were on the seesaw with two more in queue for their turn. Three boys hung on the monkey bars and kicked each other mid-air. A girl sat on a swing. Another ran circles around the wooden table and benches where some of the parents rested. There was a deodar tree behind the benches keeping them in shade, and Rajdeep dropped into a seat.

The girl wrung her hand free and ran to the empty swing. She fixed herself on the seat, shifting left and right to find a perfect balance, then fixed the fedora over her head and pushed her sneaker down on the gravel to give herself a start.

Tulika walked over to Rajdeep. “Do you want something? Tea or water or something?”

Behind his tired, drunken eyelids, Tulika could only see a shadow of a response. He waved his flask full of whiskey and shrugged.

“Well,” she said. “I think I want some chai.”

“Go find a waiter, then.”

Tulika looked between Rajdeep and the swing. The girl swung back and forth, oblivious, humming softly to herself.

“Go,” Rajdeep repeated. “I’ll watch her.”

“You…”

“I’ll watch her, Tulika.”

Could she leave? Tulika counted five other adults out on the playground. She could leave, she thought. It would be fine—why wouldn’t it be fine?

She decided to go. She left the playground and walked back through the glass doors into the hotel’s main building.

She was looking for a waiter to order chai, or perhaps something stronger. Was there a bar in this hotel? Maybe she would get some whiskey—like him—too.

No, she preferred, vodka. That’s what she used to drink before her marriage, after work with her friends outside the Tooni Graphics office in Sector 16. She would mix vodka and lemon water. Before the wars.

The main lobby was empty except for the old lady at reception, who sat with her back turned, watching a TV serial on the television mounted on the wall behind her. Her chubby arms billowed out of the sleeves of her salwar kameez and her chins sagged down below her neck. Tulika went up to the desk to ask for a waiter, but before the lady could turn around Tulika changed her mind and walked away.

Outside, through the lobby of the hotel’s main entrance, she crossed the parking area and went out the front gate.

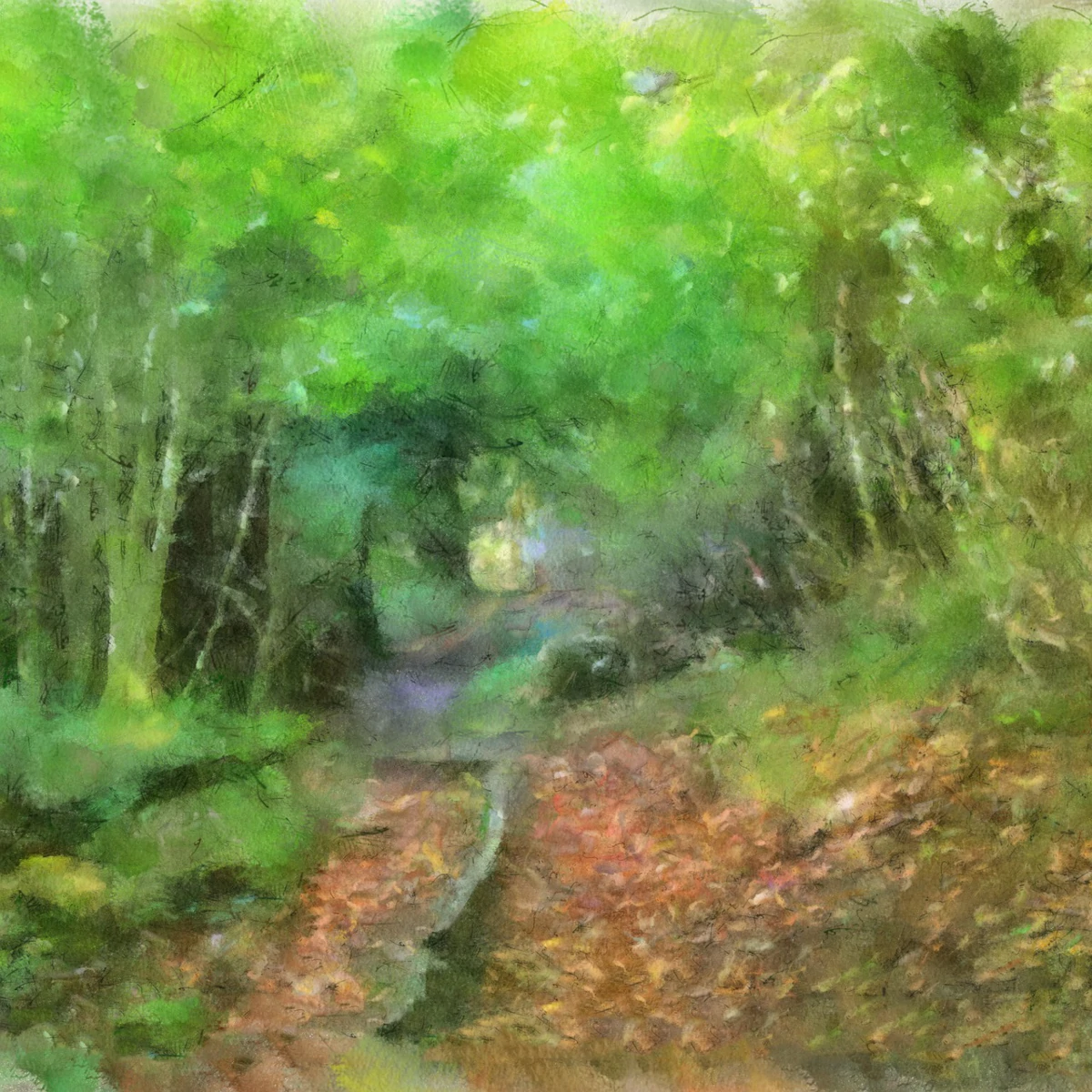

She reveled in the fresher mountain air. It felt light going into her lungs—devoid of the metallic weight of the city. She saw that both sides of the road were flanked with deodar trees, and when she heard a stray crackle of wood on her left, she strayed from her path and walked into the forest. Her feet crunched the dry leaves, and she liked the sound so much that she kept walking deeper.

It became considerably colder as the evening settled in and the tree branches overhead filtered the weak sun beams. Tulika heard the rustling of new creatures, leaping from branch to branch, scurrying through the grass, carrying on with their lives. She wondered how long she could keep walking before someone came out to look for her. Two hours? Three?

More crunched leaves. More cool air. Why couldn’t she keep walking, she wondered? Walk until she came out the other side of the forest, maybe the other side of the mountain? Where did this stony trek even lead? She could breathe clearly, too—that was good. There was no need for her to stop, was there? Wasn’t she free to do as she pleased? There was no war in the wild. There was the scent of grass and bark and a faint hint of chlorine and it all hypnotized her. She was alone.

She saw how the deodars shaded and protected the forest underneath them and she knew that she could design a logo for Dr. Joshi now. A forest. This forest. She could keep walking to the other side, yes, to the next town, and find a computer somewhere to work on it. Yes, she would do it. Why stop now? How deep in the jungle could she end up before someone yanked her back to the duties of her life, back to the girl, to Rajdeep, to the flat in Faridabad, to the world of fathers and mothers?

The girl would start school soon, and Mummyji didn’t have much longer to live, and there was more poison in the air, and Rajdeep would keep traveling to sell more motorcycle parts, and she would cough in bed on Monday night, and the WarConch would blow again and halt everything, and it would blow and it would…

It was blowing. The WarConch was blowing. She could hear it. Even in the safety of the cold forest, she could hear it. The rustling and cackling and swinging all stopped. So did she.

She needed to get back. Back out of the forest. Which way had she come? Back to the main road, to that gate, to the hotel, to the playground, to the girl. Rajdeep was there with the girl. The WarConch kept blowing, loud and consistent, propelling Tulika to instinctive urgency. Her breathing became heavy, more labored. She turned around and ran.

The hotel lobby was crowded with residents and staff, all now crouched on the floor with their hands over their heads. The old lady by the reception desk was on the floor, too, and her TV serial had been interrupted by striped saffron, white, and green bands across the screen. The conch kept blowing.

All the children and parents from the playground were back inside, but not Rajdeep, not the girl.

Tulika raced across the lobby. When she got to the glass doors, she saw them.

The girl had jumped off the swing now and stood next to Rajdeep. He was propped on one knee on the ground, close to her, undisturbed by the buzzing chaos of the conch.

Tulika watched him reach over to their daughter with those large, tense hands. With a flick of his fingers, he untied the laces of the white tennis shoe on one of her feet.

The girl bent down after him, balanced the hat over her head, and with slow deliberation, began to tie the laces back together. Stretch, loop, bunnies, pull. The girl lifted her head up to Rajdeep questioningly. He nodded, took a sip of his whiskey, and then untied her other shoe.

Stretch, loop, bunnies, pull, Tulika whispered to herself. The girl followed her father’s directions. Rajdeep nodded again.

Tulika could feel her breathing start to relax. She reached for the glass doors—intent on joining them—and then turned back toward reception. She found a spot beside the desk, not far from the old lady, next to a waiter in a uniform black vest and trousers.

The WarConch kept blowing. And as she crouched down on all fours, Tulika reminded herself to ask the waiter for chai when this was all over. Or maybe even a vodka.