The Pantheon of Writer’s Block: Meet the Gods Who Cause Creative Chaos

We’ve all been there. You sit down to write with deadlines and goals and dreams fresh in your mind, and suddenly your brain empties. Your fingers freeze over your keyboard, and the blinking dash on the screen mocks you with every second that passes. Here lies the telltale signs the infamous writer’s block has found you once again.

But I come bearing answers. After journeying far and wide, risking life and limb in the perilous jungles of writerdom, I’ve finally uncovered the lost pantheon of writer’s block—that dreaded nemesis of every writer’s existence. And in this pantheon of half-written books and dusty notebooks, I’ve met and documented the dastardly deities that exist just to mess with innocent writers like you.

Now, before we dive into my findings, I know what you are going to say: Bekah, I’m just a human writer. How can I defeat these otherworldly beings? Fear not, dear friends, for with these exclusive godly introductions, I offer the key to their downfall—their Achilles heel, if you will—and if you follow these tips and tricks, you will soon defeat each of these deities and the blinking dash that mocks you with its repetition. Stick with me, kid. You’ll go places.

I’ve risked a great deal to reveal this information to you, so without further ado, please let me introduce the accursed forces behind our every writerly strife: the gods of creative chaos.

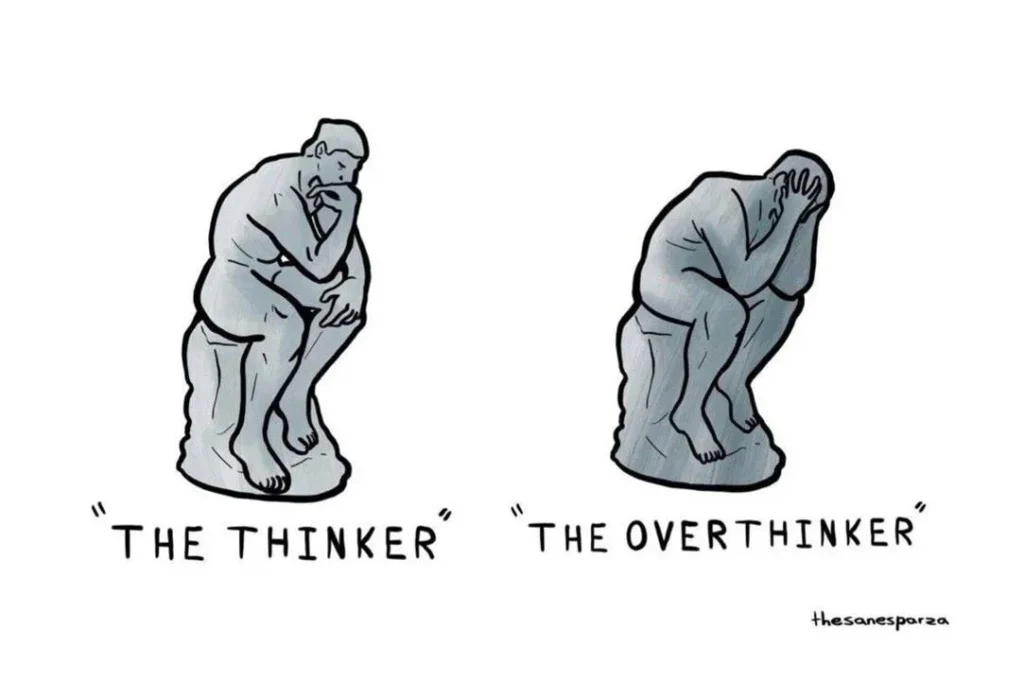

Analyzia: The Goddess of Overthinking

First on our list of introductions is Analyzia, the goddess of overthinking. Analyzia’s divine domain resides in the blank page, in the swarm of mosquito-like thoughts buzzing through your brain at the most inconvenient of moments, slurping the productiveness from your veins like sugar water. Her favorite trick is making a simple concept suddenly complicated and confusing, leaving you running circles trying to get out of the plot hole you’ve walked yourself into. She constantly sings an off-key chorus of, “Are you sureee you want to make that your final scene?” and “I feeeel like you’re missing somethiiing!”

How to Defeat Her: Don’t think; just write! This goddess is terrified of “word vomit” and the beautiful creative freedom that comes with getting that idea in your head down on the page. This is especially important in the beginnings of the writing process—consider Analyzia officially evicted from these early stages. Kick her to the curb if she tries to edit before your story has the chance to fully get out of your brain. While this can be hard at first, like a muscle it gets stronger with consistent use. Just remember your words are worth writing, regardless of what Analyzia thinks. You can edit and revise later; for now, have fun and let your imagination run free and true.

Procrastius and Tangentius: The Twin Gods of Procrastination and Tangents

You know that friend who recently got out of a toxic relationship and said she would never talk to him again, only to mention weeks later they are back together, happier than ever, and this time will be different? Yeah, that’s me with Procrastius. You’ll recognize this sneaky trickster in the buzz of your phone when you get a notification, in the tantalizing smell of hot coffee at the coffee shop down the road, and in the sudden overwhelming enticement of every single tab open that doesn’t have your book draft open. His divine domain resides in excuses and delays and is magically summoned any time a writer utters the following enchantment: “Oh, I’ll have time for that later.”

Procrastius’s twin brother, Tangentius, on the other hand, really, really wants to be your friend, but is sometimes just not good for you. Like his twin, he specializes in detours and wildly off-topic thoughts. His divine domain resides in your search engine history; one second, you’re writing about a character’s internal monologue, and the next, you’re googling the history of medieval sandwiches.

How to Defeat The Twins: If you’ve been caught in Procrastius’s snare, don’t worry; we’ve all been there. Just like avoiding your toxic ex, the goal here is to be proactive and purposeful with your decision-making. Document your daily work patterns while being reflective and honest about when you are most productive, and when you are most likely going to text Procrastius and ask him to come over. When you feel yourself itching towards your phone, internet browser, or even another writing project—eliminate those distractions. Put your phone in another room. Close those tabs. Write yourself a sticky note about what you want to work on in that other writing project and set it aside for later. Another thing Procrastius hates—setting achievable daily goals. Starting your day off with a sticky note of realistic goals you can cross off as you go—it’s like garlic to a vampire for Procrastius.

As for Tangentius, occasionally he can lead to some fruitful discoveries, but often at inopportune times. So, to effectively use the awesome yet deviating powers of Tangentius, I would suggest writing down all the tangents he gives you in a notebook before refocusing back on the writing at hand. Set a timer, write your spiel, and then go on a fun adventure with Tangentius once your daily writing goals have been achieved.

Perfectionia: The Tyrant of Perfection

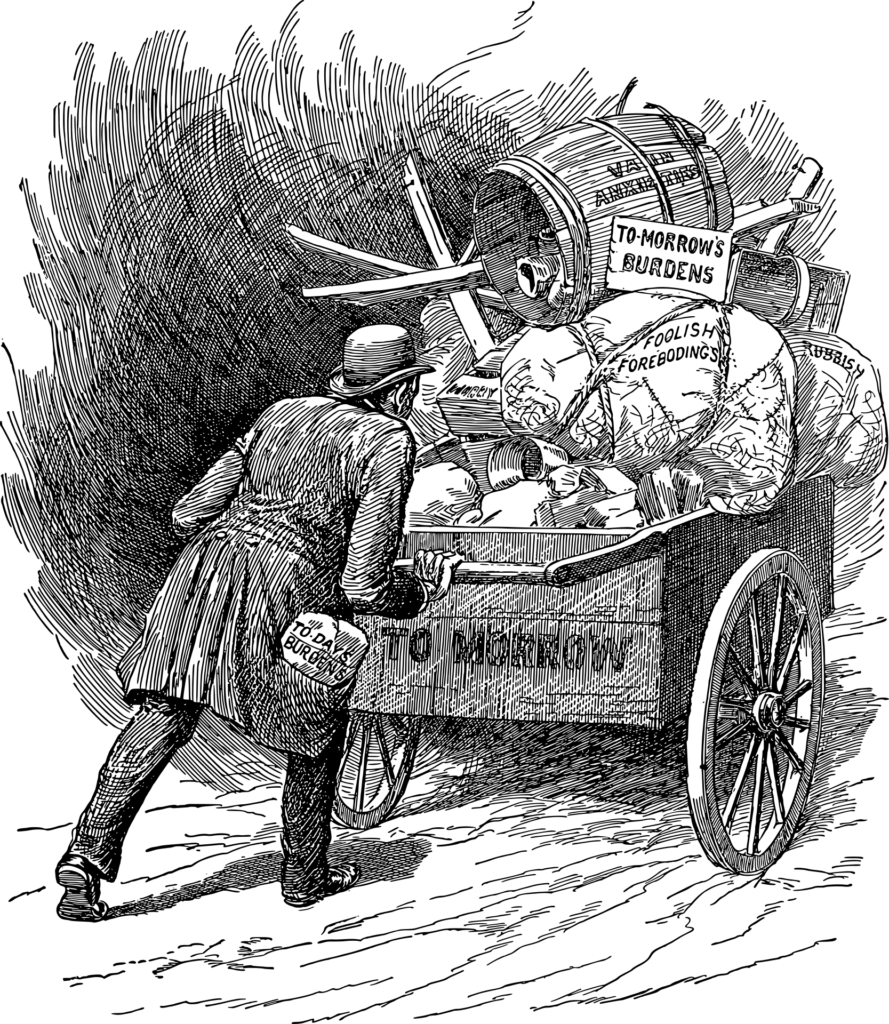

This deity, unfortunately, is one all writers are well acquainted with. Perfectionia is the supreme overlord of the pantheon of writer’s block, the big kahuna, the final boss. Her divine domain resides in the expectation of flawless writing, constant self-criticism, and lingering self-doubt. Perfectionia’s power invades both ends of the writing journey; if she catches you near the beginning of the writing process, the weight of her demands to be perfect right off the bat can paralyze creativity and steal the joy of working on your passion project. If she catches you near the end of a project, she can trap you in a purgatory of never-ending, relentless revision. In both traps, she loves to whisper, “Not quite good enough” in your ear, over and over again. She is a deity we all face.

How to Defeat Her: EMBRACE IMPERFECTION. Perfectionia might always be whispering in your ear, but the good news is you don’t have to listen to her. Instead, you can embrace the beauty of the journey, knowing your progress as a writer is the most powerful thing in the world. The progress you make and the journey you take is something Perfectionia can never take away from you. So, tell Perfectionia to take a hike. Write that messy first draft. Get those dreams on the page. Celebrate every word you write and know it drives this deity absolutely bonkers to see you embrace the journey and focus on progress rather than her own whispers for perfection. Write that story the world longs to hear—because we do indeed long to hear the imperfectly perfect stories you’ve yet to tell.

Triumph Awaits

Before we part, let me tell you the greatest discovery I made when I found the pantheon of writer’s block: these deities of creative chaos, despite what they would have you believe, are far from all powerful. They cannot defeat you. Not if you don’t let them. Because no matter how hard they scheme and trick, they will never be able to stop your creativity, your passion and joy, nor stamp out the writerly spark that makes you keep coming back to the stories that make your soul sing. And remember that every time you sit down to write—it’s a victory. Because even though these gods of creative chaos will always try to derail your progress, you grow stronger with every battle. Because, in the end, your stories are your weapons, and victory is always just a pen stroke away.