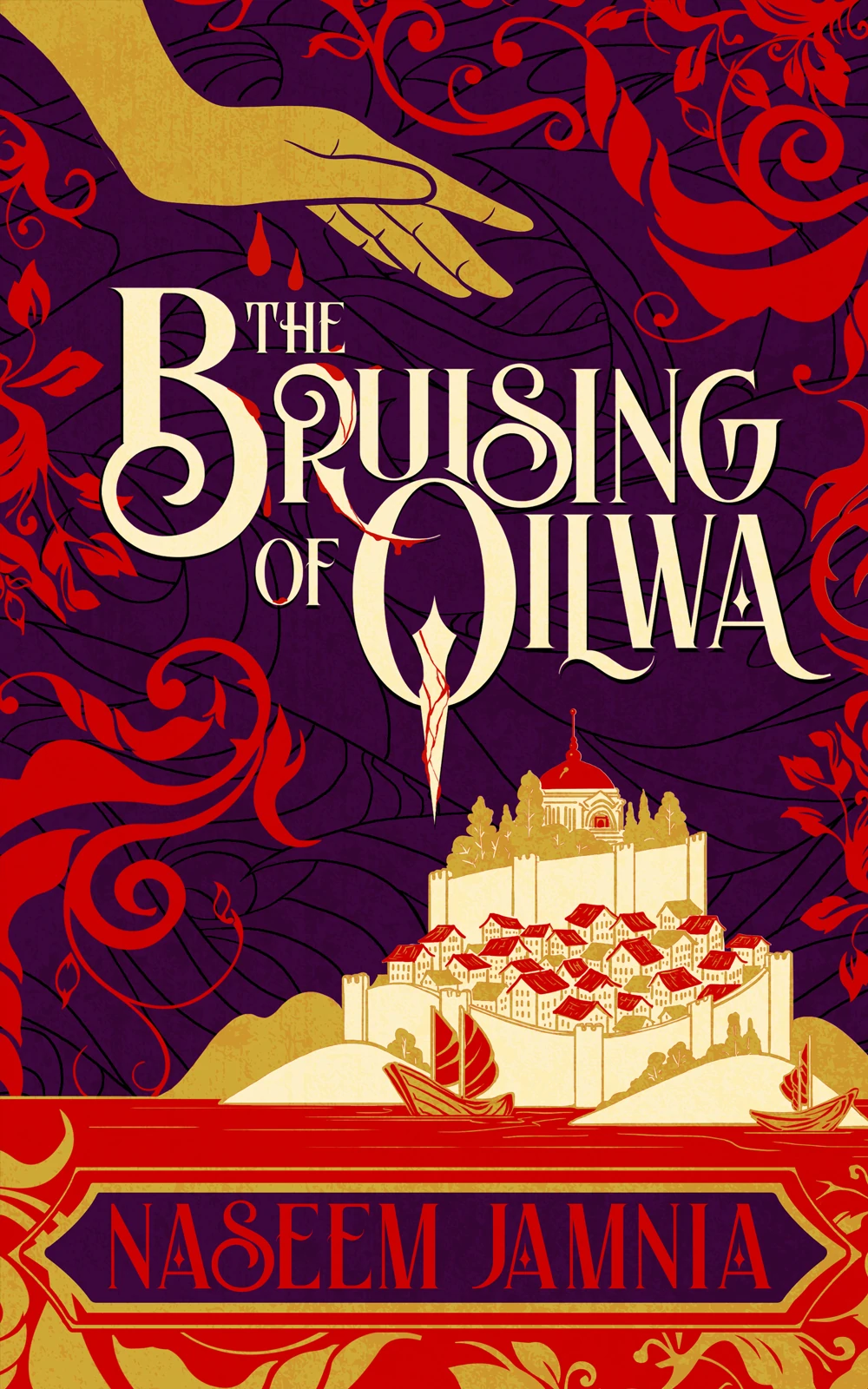

Firstly, congratulations on being on Tor.com Reviewer’s Choice: The Best Books of 2022 list! For readers not already familiar with The Bruising of Qilwa (Tachyon Publications), could you give an introduction to the book?

Thanks so much! I was so delighted that Marty Cahill put it on there and that Alex Brown gave it a shout-out.

The Bruising of Qilwa is a slice-of-life novella introducing my queernormative, Persian-inspired world. It follows Firuz-e Jafari, an aroace and nonbinary refugee healer who seeks a job at a free healing clinic in their new home of Qilwa. Firuz arrives in Qilwa during a plague which is being unjustly blamed on the refugees, and soon, Firuz is confronted with mysterious bodies whose marrows remain active upon death. As a secret practitioner of blood magic—which is stigmatized and poorly understood—they realize this phenomenon may be related to the misuse of blood magic and have to decide what to do with that information.

If you’re a fan of found family, grumpy caregivers adopting powerful and traumatized orphans, an all-queer and BIPOC cast, scientific magic systems, complicated discussions of colonialism and empire, and standalone stories in a larger world, then Qilwa might be for you!

When we last spoke for Hope For Us Network’s Suicide Prevention event, we talked about healers and self-care. Can you talk about personal levels of self-care as part of healing, as the book demonstrates? And how food serves the story to make this point?

I was so glad to be a part of that event—as someone who has multiple psychiatric disabilities and is a suicide attempt survivor, destigmatizing mental health is an important facet of my personal mission. One part of that is normalizing self-care, but also normalizing when you are unable to care for yourself and need help.

Speaking from my own experience, learning to prioritize self-care is one way to recoup from life’s traumas. This is particularly true if you’re a marginalized person. In a world that tells us our bodies are too much or not enough, or our ethnicity or race makes us too different, or that who and how we love is too weird, taking time to check in with yourself feels like a luxury and an act of defiance. We are often told, especially as marginalized people, that we don’t deserve to take time for ourselves, or doing so will somehow result in something negative.

Yet, in my own healing, I eventually saw self-care as indispensable. I couldn’t heal—not from abuse, not from childhood trauma, not from moving through this world as a queer and trans person of color—until I prioritized myself on some level and, importantly, believed I was worthy of that time and energy. As Audre Lorde said, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

And the truth is, Firuz does not do that for themself. Firuz has a traumatic migrant experience on top of unresolved childhood trauma related to their magic training. Much of The Bruising of Qilwa is about how stretched thin they are. And because Firuz never takes the time to prioritize themself, and on some level doesn’t believe that they deserve it, they make choices that harm themself and harm other people. They are unable to be there for themself or for the people they love.

One way that they try to connect particularly with their younger brother and the orphan they adopt is via food (something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately!). In Persian culture, cooking is such an act of love. A lot of our dishes take hours to prep, so taking that time is really showing someone that you care. (The culture Firuz is from in the book is Persianate, so they have this same philosophy.) In The Bruising of Qilwa, there are lots of food shortages, and many migrants are in extreme poverty. Firuz often goes hungry in order for their family to eat (and also sort of as self-punishment given all they cannot help—or control).

For me personally, cooking is a huge act of self-care for multiple reasons: besides the fact that I love cooking, creating something that nourishes my body and my spirit helps care for my disordered eating brain. (I have a history of eating disorders, and much of my self-care routine is about keeping those disordered thoughts in check so as not to go back.) So, when you cook for others and yourself, you’re saying that you prioritize your own health as well as those you care about. Firuz doesn’t quite learn that by the end of The Bruising of Qilwa, but they’re getting closer.

Since we are still in a pandemic going into 2023, what lessons can we learn from the healer characters Firuz and Kofi in the book on how not to lose hope and keep showing up?

THANK YOU for acknowledging that we are still in a pandemic. I am literally the only person I know who still wears a mask everywhere. Frustrating.

Anyway! One thing to not learn from Firuz is to show up because you’re punishing yourself. Kofi (their employer and mentor at the clinic) is actually a really great model for this—he shows up because he fights, every day, for the right to exist and for people less fortunate than him to exist and thrive. Because here’s the thing: the people that make showing up difficult, or who are fighting against the progressive changes we’re trying to realize, will keep doing what they’re doing. And if they’re doing that, shouldn’t you take up space too? Shouldn’t you also make sure your presence is known? Kofi very much believes in using his positionality to advocate for those who don’t get a seat at the table. Given the political landscape in Qilwa, that actually is how he can do the most good.

But you have to care for yourself. Kofi frequently sends Firuz home to rest and take time with their family because he understands the value of self-care. If you’re pulling a Firuz and pushing through every day because you don’t know what else to do, you will burn out. You will give up. But we’re not the only ones who need you—you need you. How does what you’re doing feed into the life you’re building for yourself? Or the story of yourself you tell yourself?

Showing up might sometimes mean taking a step back. It might mean shifting your energy into something else. But that’s still showing up! You have to figure out what you’re showing up for and why. The “for whom” is obvious—you and the people you love. If it helps others too, that’s a bonus.

We need more diverse books like The Bruising of Qilwa. Would you like to talk about your afterwords in the book as schools and libraries were facing ongoing censorship about what can be on their shelves in 2022?

With Qilwa, I definitely wrote the book I wanted to see in the world, one where the fundamental assumptions of secondary worldbuilding were shaken up to be more inclusive. So thank you!

In my afterword, I talk mainly about the context in which the book came about: my parents are Iranian immigrants, and I grew up hearing about the mighty Persian empire. And then I started on postcolonial studies and realized: wait, this is still empire, and empire and colonialism has been a fundamental force of oppression in our world. Quickly, things became thorny. The central question the book asks is, “what does it mean to be oppressed when you were once an oppressor?” This question has been driving my writing for the last several years. It’s coming from a place of marginalization and trying to figure out my place in society—in both the real one and the ones I make up.

Censorship comes from a place of fear. People who are not marginalized feel threatened—feel like their power will be taken away. So they retaliate with book bans and by fighting schools and libraries. They have long been the center of the world, and they fear that being told others exist means their children will receive the same treatment that marginalized kids do.

But if we want to raise kinder, more empathetic, more compassionate people, we need to expose kids to ideas that make them uncomfortable. Discomfort in this context is good. It means you’re being challenged. Learning there is more to the world than just you is an important milestone.

Countries and cultures are invested in perpetuating the myths they tell about themselves. In the US, this is the story of the American Dream and the Land of Opportunity and what have you. But when we indoctrinate our children into that mindset, they don’t learn critical thinking skills. They don’t learn that critiquing systems of power is how we can keep them just. And those critiques demonstrate a marked investment in these systems. Why would you bother critiquing something you don’t care about?

Thanks to technology, we live in a globalized world. That means we’re constantly being faced with other ideas. Not all other ideas are good, but many of them cause us to consider others rather than just ourselves.

And honestly, most kids get it. Kids have to learn prejudice and hatred and exclusion. So many, when you explain the natural variations of humans, accept it and move on. Kids will not be harmed by reading books that challenge them. They often look at things with more nuance than adults. And I hope, for any adult who feels threatened by these ideas, that they sit with that and think about where it’s coming from and what happens if they let it go.

What would you say to a reader who connected with the characters and themes in your book but then read the national & global news in 2022 with topics like the Colorado shooting on Trans Day of Remembrance and the IRI’s brutality against the women and indigenous workers protesters?

Thank you for bringing up what’s happening in Iran right now. For those who don’t know, in September of last year, a Kurdish woman named Jina (Mahsa) Amini was arrested by regime forces and brutally beaten to death. The regime tried to cover it up, but it sparked nationwide protests that are still going strong. The Islamic Regime co-opted a revolution over 40 years ago and uses the language of religion to justify brutality, including executing their own citizens because they’re protesting. They have killed over 500 protestors, over 65 children, started executing people in December (several of whom were younger than 23 years old), and have poisoned thousands of children with targeted gas attacks in schools. If you’re interested in learning more, you can check out my ‘Iran Revolution’ highlight on Instagram (linked below), where I highlight some organizations or pages worth following, or look at various hashtags like #StopIranExecutions and #MahsaAmini and #WomanLifeFreedom.

Simply, I write speculative fiction to imagine better worlds. I wrote The Bruising of Qilwa as a queernormative world precisely because massacres like the Colorado shooting in 2022 happen. It will never make sense to me that people want to have magic and dragons but not include queer people in their work. When you’re literally making up a world, you have the choice to replicate real world oppressions—or to dream up something better. In her introduction to the Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2018, N.K. Jemisin talks about the revolutionary potential of speculative fiction. The postcolonial scholar Lorenzo Veracini argues that literature reflects the cultural imaginaries—that is, what we as a collective can view for the world. Postcolonial and decolonial literature that reimagined possibilities for what countries could look like after or without colonization directly impacts how we move forward. Literature matters. Dreaming up something else makes a real difference.

Find revolutionary work. And if you can’t, make your own.

What upcoming work can we look forward to seeing in 2023?

2023 is a year of me (hopefully) selling projects for 2024 and beyond. My agent and I are waiting to hear back from editors on a novel set in the Qilwa universe, and I’m revising a lightly speculative YA contemporary that I hope to send this year as well. I have a short story out in a 2024 YA horror anthology called The White Guy Dies First which I’m really excited about, and my debut middle grade horror, Sleepaway, comes out in 2025 from Aladdin.

I will hopefully have some nonfiction pieces out this year, though, likely through Sidequest.Zone, the gaming criticism website I used to be the managing editor for. Furthermore, as part of their Personal Canons Cookbook, author Sarah Gailey published a lyric essay I wrote called “Cook for Iran: Making Khoresht-e Bademjoon When I’m Homesick” in January. I’m honored to be the opening essay for this series, and it includes a recipe for a Persian eggplant stew that Qilwa readers will recognize as something Firuz’s little brother Parviz has strong feelings about. I also had a piece in New Orleans Review’s beautiful Iran issue called “Passing: An Elegy in VIII Parts,” about invisibility, privilege, race, and gender.

I always share any updates in my Tuesday Telegrams, my newsletter which comes out twice a month (one is a personal essay, and one is writing updates/craft related).

There is a hardcover of the book now coming out from Rainbow Crate. What can fans of the book find in this new edition?

I cannot wait for readers to see this exclusive hardcover!!!! Danielle and Jaime at Rainbow Crate have worked really hard to make this the version of my dreams. There is an entirely new cover and art endpages by Pauliina Hannuniemi, whose style is so beautiful and captures the book in such a special way. Jaime designed an internal map as well, and the edges will be printed. There’s another special external feature as well, but I want to save those details, so let me just say: if you think you can guess what a spellbook looks like in the Qilwa universe, think again!

As for the internal differences, I’ve written an author note about the queernorm world of the story, and also included a short story alternative universe retelling at the back of the book for readers to see what QILWA could have looked like!

I cannot wait to get my hands on this edition. It’s going to be beautiful!!!

Where can our readers find you online?

My newsletter is the best way to keep in touch with me, but I’m also on social media as @jamsternazzy on Twitter (rarely nowadays), Instagram, and Mastodon. There’s also my website, where there’s more information on me and the book! I hope to connect with many more readers this year!! Thanks so much for having me!