Anatomy of an Epic Poem

Words By Bea Basa, Art By Sreten Vukovic

What exactly makes an epic, “epic?” What makes a journey “heroic,” and a hero “divine?” Much like human anatomy, every epic is defined by a set of parts. Some parts may be missing, while others could look different; but each part is unique, and its structure remains largely the same. It’s the tropes codified in these epics that form the body of modern storytelling—high fantasy, space operas, comic book superheroes, you name it. The survival of this structure into the modern age is truly a testament to the timelessness of epic.

From Arthur’s crown to Achilles’ heel, every part has a role to play. Journey from head to toe with me as I navigate the anatomy of an epic poem.

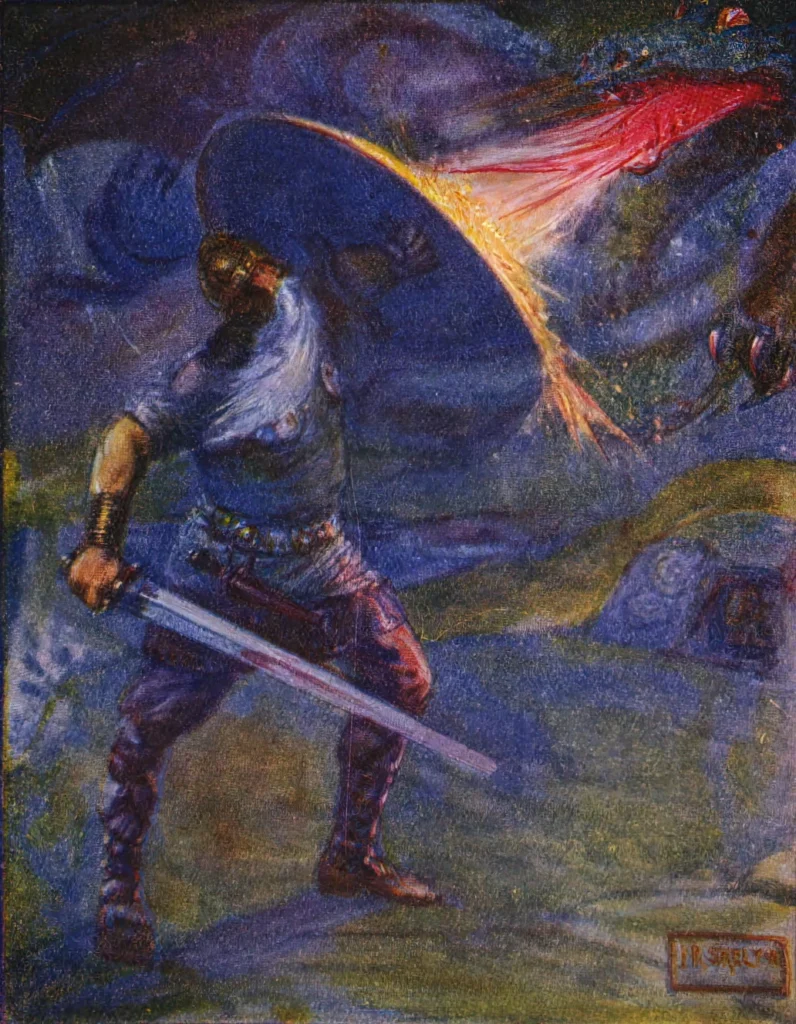

Hands of Beowulf: Divine Hero

At the center of every epic is the divine hero. Either they’re a god’s (usually half-mortal) offspring, or they’re protected by a patron god. These hands are named for Beowulf, the divine hero of his namesake. In his case, his patron is the Christian God, whom he believes granted him his “mighty strength.”

In this Old English epic, Beowulf realizes he can’t harm the monstrous Grendel with a sword, so he declares instead that “hand-to-hand / is how it will be.” He eventually triumphs over Grendel by ripping his arm from his shoulder. Beowulf makes a point of thanking his God throughout the poem, doing so even in his last breath.

Arms of Gilgamesh: Tasks of Superhuman Valor

No hero’s journey begins without a mission. From Hercules’ Twelve Labors to Jason’s journey for the Fleece, each epic hero has their own equally epic tasks to complete. These arms are named for Gilgamesh, the Mesopotamian hero-king of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Using his superhuman strength, he single-handedly built ziggurats, walls, and orchards for his beloved city of Uruk.

Godlike in appearance and feats, his initially lecherous character made him fall short of divinity. He meets an equal in the wild man Enkidu, and they quickly become inseparable. Enkidu’s death at the hands of the gods spurs Gilgamesh to find the secret of immortality; through these perilous quests, he learns grief, humanity, and how to use his strength for honest kingship.

Legs of Odysseus: Travel Across a Vast Setting

But what fulfillment is a quest without a long and arduous journey? Whether geographical, cosmological, or between space and time, the hero must traverse through a vast setting to complete their goals. These legs are named for Odysseus, the cunning Greek hero-king of The Odyssey, who runs, swims, and sails his way back home.

Odysseus’ ten-year homecoming voyage from Troy to Ithaca is perhaps the definition of “hero’s journey.” The gods observe his journey, and their constant intervention is to both his benefit and detriment—it all depends on who’s at the helm. Only after a long, long decade does he finally return to Penelope and Telemachus.

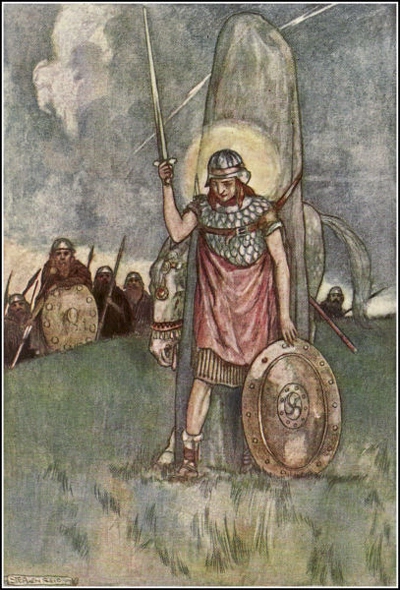

Eyes of Cú Chulainn: Omniscient Narrator

Every epic poem needs its storyteller. An omniscient narrator, all-seeing and all-knowing, is the backbone of every heroic tale. These eyes are named for Cú Chulainn, the Hound of Ulster, demigod hero of Ireland’s Ulster Cycle. Revered and feared for his battle fury, he was said to have seven fingers, seven toes, and seven pupils in each eye. These pupils, associated with the evil eye, symbolize both clairvoyance and destruction.

Cú Chulainn’s most famous episode is recorded in the Táin Bó Cúailnge. In this tale, Queen Medb of Connacht wages war against Ulster for the capture of Donn Cúailnge, a stud bull. A curse on the Red Knights of Ulster leaves them unable to fight, leaving only Cú Chulainn to fend them off. His bold and bloody defense buys the Knights time to recover, and Ulster prevails over Connacht’s forces.

Heart of Gawain: Moral Code

An epic poem is no good without an overarching moral code. The lessons a hero learns across their journey are just as definitive as their feats, and it’s only through enduring them that they become a symbol of greatness. This heart is named for Sir Gawain, a Knight of the Round Table and Arthur’s closest companion. Described as “good / […] like gold well refined,” he was renowned for his humility, spirituality, and chivalry.

Gawain’s encounter with the Green Knight is his most recognized tale, and certainly his most virtuous. The Knight challenges Arthur’s court to behead him, promising to return the blow a year later. Gawain steps up to the challenge, and in that year, his integrity and honor are repeatedly tested—sometimes in pretty “un-knightly” ways. Though Gawain has his highs and lows, he remains loyal to his code of honor and Christian morality. It’s his repentance of his sins that convinces the Green Knight of his goodness, and he spares him.

Understanding the anatomy of an epic poem means understanding story itself. Although it’s by no means a static set of ideas—and perhaps there’s some I missed!—it’s important to remember that mythology and folklore are the reason we write stories today. For more tales inspired by epic heroes, look no further than the latest issue of F(r)iction.