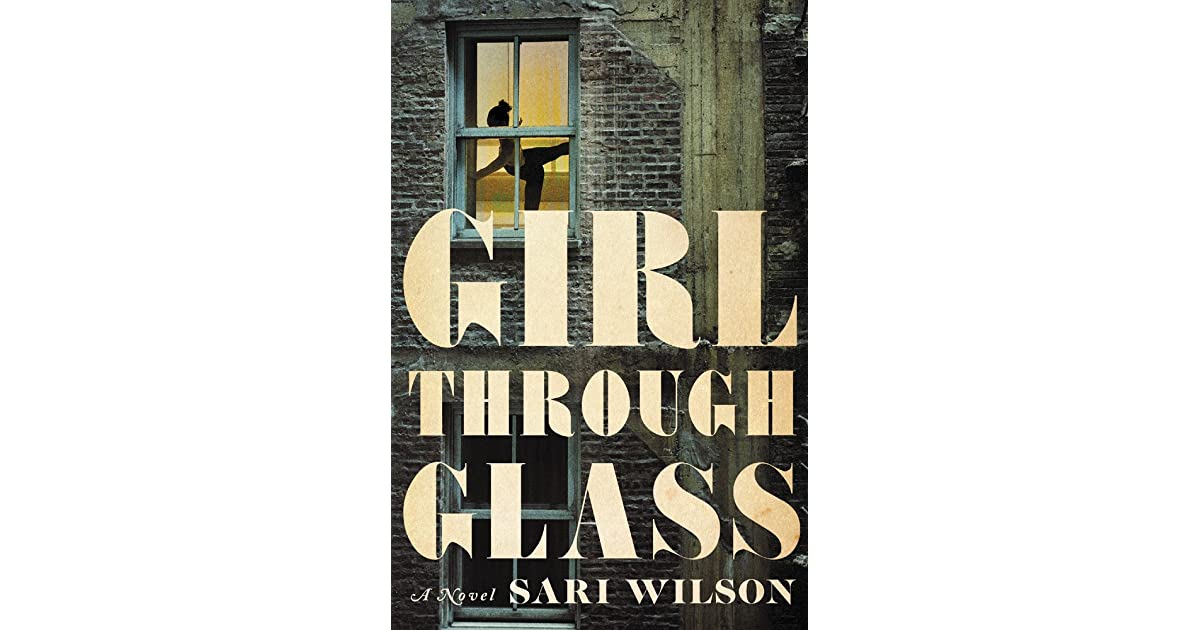

An Interview with Sari Wilson on Girl Through Glass: A Novel

Words By Sari Wilson, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

I loved this book. I rarely interview writers anymore, but the moment this fell on my editor’s desk, I picked it up and couldn’t put it down. It’s so compelling.

Wow, thank you so much. That’s incredible. It’s what every writer dreams to hear.

It seems like you didn’t start out saying, “I want to be a writer.” You came from a different background. Talk to me about the transition into becoming a professional writer.

I always liked writing. I was good at it in school. I enjoyed it as a craft. But I was training as a dancer. I think that was my creative outlet and my identity for a long time. It really wasn’t until I left the dance world when I was about eighteen or nineteen that I became very serious about writing as a creative endeavor. So, I’ve had a really long apprenticeship. I think a lot of writers know from a very young age, on some level, that they want to be writers and so, in some way, are unconsciously training from a very young age. I think that I spent my twenties, and probably my thirties too, doing my apprenticeship. Luckily, I had some really great help along the way.

I got the Stegner Fellowship and then the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center Fellowship. So I had three years of writing fellowships. That time off from working—journalism in my twenties and educational publishing in my thirties—kept this apprenticeship going. I was very committed, always writing on the weekends, in the evenings, on my lunch breaks. And I published some stories along the way. What I’m trying to say is it has been a slow process for twenty-five years. I’m in my mid-forties now. And this book—I put everything into it. I wrote it in pieces through so many different parts of my life that it’s all sort of in there. Some people say to me now, “I can’t believe this is your debut novel.” But, in a way, it doesn’t feel like it because I wrote it and rewrote it so many times. I learned so much along the way.

I grew up on a dance background as well, and it was very strange to hear terms that I hadn’t heard since I was a teenager, like “pain is pride.” I think that a lot of young writers will get into writing and they’re happy to do the writing part, but when it comes to the revisions—the manifested pain of writing—they really shy away from that. Your prose is so sculpted, and it doesn’t read like a debut at all—you were definitely not afraid to get into the pain of writing. I wonder if that was influenced by your strong dance background because it was so perfect by the time it hit the page.

Your perspective is so interesting. It’s a very particular kind of training you receive as a dancer. That pride you are trained to take in suffering and pain, for better or worse, is really something that I think is hard to unlearn, or maybe impossible to unlearn. For me, the prose is hard. Maybe that’s the part where I feel comfortable with the discipline of writing. I don’t feel like everything I write has to be perfect. In fact, if there’s one thing dance did not help me with, it’s this idea that things have to be perfect. I had to really unlearn that because writing is so much messier. And it took me a long time to allow myself to fail and really write a bad draft, to be able to see it as a process. Dance, I think, is more performative. You’re working toward this single moment of performance. That correlation is not really one to one with writing, which I find so much more process-based.

To be able to have that pure moment where you are perfection on the stage is amazing. You never really get that as an adult.

My editor really understood that that’s what the book was about. It’s a moment of youth in which there can be this moment of transcendence through art, through movement, through creativity. It’s a very special moment, and if I were to have danced in my adulthood, I wouldn’t have been able to sustain that. It is a moment of youthful passion. And it could be dance, it could be a sport, it could be a passionate love that you have when you’re young that you can never quite recapture that level of pure passion. The giving up of that moment is explored through Kate.

One of the things I find so interesting about this novel is the difficult sides of dance that no one really sees unless you’re a dancer. Was it difficult as a writer to be that honest?

Getting to the emotional truth was hard. That’s probably why I would say this took me a decade or more. I kept having to put it aside and figure out where I was going. I had to work through a lot of emotional stuff to get to a place where I could be really honest. It helps that this is fiction. When I first started with the material, I thought maybe I was writing a memoir. So I tried to write about my own experience. But it really never took off. There just wasn’t a lot of energy in it and I finally realized that my experience in dance was A) not that unique, and B) not that compelling, dramatically. Yet there was something there that I really wanted to get to. So I actually decided I was going to interview girls that I had danced with when we were children. Some of them became professional dancers for a time; others left earlier than I did. It was really all over the board. And basically, this character, Mira, started to emerge. She took me to places that were hard to go to, and I felt like I had to be really honest with myself. She went to places where I did not go, and she has experiences I did not have. And they’re difficult. She has a difficult home life, she has both amazing talent but also a great innocence that costs her a lot. So yes, it was very hard. But I felt that the book demanded that. If I were going to write this book, that was what I was called to do: be very honest about my own experience only so I could be honest about her experience.

I’m so interested in the dual narrative that you set up. What was it like to approach this one craft from so many different angles?

I wrote the narratives separately. I wrote the Mira story first, all the way through. Then I showed it to some people in publishing, and there was a question whether it was YA because of the age of the protagonist. Around the same time, I had my daughter. So I actually had to put the book aside for a few years. But in those moments that I was able to write, like ten minutes here, fifteen minutes there, I was getting this other voice. This first person voice which became Kate. I showed it to my writing partner at the time and he was really interested in it. At a certain point I decided, like with the Mira character, this voice was kind of taking me. The interesting thing about her is that she’s not very likeable. I had to make a conscious decision to go with her even though the initial reads I was getting on her was that this is a difficult woman, she’s not particularly likable, and that could hinder possible publishing interest.

That’s a really brave move as a writer.

In a way, I didn’t have a choice because I learned by then that for me, as a writer, I needed to give myself over to these characters and this seemed like another one of them. So I took a few years and I wrote her whole story. But along the way, I did try to interweave it with Mira’s story. I had to adjust that a lot after it was written, but that was when I got excited because I thought, this is a book. I don’t know if it’ll ever be published, I don’t know if people will like it, I don’t know if it’ll ever see the light of day. But it felt like an actual book having these two narratives working off each other.

This was a very long writing process. How many years between the conception of the idea and seeing it in print?

I’m going to be honest: fifteen years. But I didn’t work on it all that time. The first glimmer of it was when I was all the way back in graduate school at Stamford. I sat down in a free writing session and I wrote the first scene in the book where these ballet girls are getting ready for class and they’re pulling on their tights and their leotards and their hairpieces and their elastics and the sort of uniform of the dance world. It’s like they’re getting ready for battle. That came to me pretty much unbidden, and I wrote that in one burst. And then I just cried. I didn’t know what to do with it because it was so different from anything I was writing at the time. I was writing mostly about men, about ex-patriots. I was reading all these ex-patriot writers, from Hemingway to Jean Rhys to Henry James. So it just seemed like everything that I wasn’t interested in. It was about girlhood, it was about youth, it was about New York City. I put it aside for years and I wrote short stories. But I just kept coming back to it. And then I would commit to it in spurts. For a couple of years I would really, really, really write… and then I would back off.

How did you go about publishing? You had written some short stories. Did you do the traditional querying an agent route? Or did someone find you?

At some point, I had 75 pages of the novel. I queried some agents and I got a good response. I felt encouraged enough by the response that I thought to myself, “I’m a slow writer, but I can invest in this project.” Then I published a story in AGNI and some agents approached me. But I didn’t have enough of the book. When I finally had a complete draft that I felt good about, I used all of my publishing and writer contacts. I got together a list of fifteen agents. I researched in Poets & Writers. I looked in the acknowledgments of all the books I had loved, and I made a chart. I made lists. I was very businesslike about it. I attached the first ten pages with my query letter, and I got a lot of interest. My agent is PJ Mark of Janklow & Nesbit who has helped the book immeasurably. I actually queried him blind. A wonderful woman in his office named Marya Spence first read the letter and loved the manuscript and she got it into his hands and then it happened very quickly. He pitched my book to me and I knew that he understood the book, he had a vision for the book, and it was very exciting. I feel very fortunate to have found somebody that I connect creatively with and in terms of an aesthetic vision. I worked with him for a year on editing and then he submitted. And again, I was lucky enough to have a good amount of interest and the book sold at auction to Terry. I met with Terry, met with a few editors, and I felt, again, as with PJ, very strongly that she really understood this book in a way that maybe even I, for all the years I had spent on it, didn’t. She had a vision for it. And I was honest with myself in the sense that I still needed more, the book still needed yet another round. It needed another hand. She had me mostly work on the Kate narrative. I rewrote that storyline. Even though it was an extraordinary amount of work, it felt necessary and I feel like the book is in its right, final form. I feel so fortunate that these two people were able to help the book find that final form.

After these fifteen years and so many drafts and visions, what does it feel like to hold this finished book in your hand?

At first it felt surreal. I never really thought that it would happen, even though I hoped and dreamed it would. But now that it’s been out about two months, I feel really gratified. I feel fortunate and very grateful that so many people are interested and seem to be compelled by the characters and the narrative and that it’s opening up a lot of windows for conversations about all sorts of things: parenthood, girlhood, art, the 1970s, New York City, identity. I’m just really enjoying getting to talk to people about the process and about the book because, for me, it was such a private experience for so long that was mostly an internal process. To be able to have it be externalized is a dream come true. It is very special and very moving.

We talk about what it was like to feel those moments of perfection as a dancer. How does writing this book compare to that kind of joy?

It’s very different, actually. When I performed as a dancer, it was truly an effervescent moment. When it all comes together and you’re being led by the movements and you’re connecting with the audience, it’s exhilarating. But it’s a moment in time that then is over. I think that’s why it’s so hard to capture dance on film. Because it’s really a performative art and to be in the audience is a cathartic thing. You’re experiencing with the bodies in space and time. But writing and literature seem to happen in a different space. It’s more complicated and these spaces can overlap and conversation can keep going over time and deepen. So it’s a different kind of culture. And it’s a different kind of performance. I guess I don’t quite know yet because it’s still early in this process for me. But it feels different and maybe even more gratifying. Because it’s not lost to time in that same way. I mean, that’s the beauty of a book, right? The book continues to exist even after writers pass on. And some of the books I’m sure you love and loved as a child, they were written a hundred years ago. Yet they continue to be new. That’s pretty special.