An Interview with Sam J. Miller

Words By Sam J. Miller, Interviewed by Dominic Loise

Cities in survival mode is a theme in your books. Can you talk about the correlation between gentrification of Hudson in The Blade Between and global warming in the futuristic sunken world in Blackfish City?

I think both books spring from a similar feeling of frustration and anger about similar problems. They’re deployed in really different genres, so horror and science fiction play out really differently in terms of how you can talk about policy and how you can make policy fun, if that’s possible. I think that at the root of things like gentrification and global warming, there’s this issue of people who are really wealthy and comfortable and benefit from a bad situation and therefore have no interest in changing it. Then there are people who are negatively impacted by a situation but have no real systemic power to create change. When you are dealing with these imbalances where people are benefitting from a bad situation and they see no reason to change, how can we make them change? That’s going to look really differently if you’re talking about small-town gentrification or far future climate change. The plot complications that arise are dictated by the genre and the technical challenges of grappling with policy in fiction.

Blackfish City talks about people “bringing their ghosts with them” to Qaanaaq, Greenland. How does manipulation of loneliness when community collapses come into play with these cities, like Fill finding comfort in the unknown author of “City Without A Map” in Blackfish City and the catfishing used in The Blade Between?

I think the bottom line in a lot of my fiction is that life is really hard, and we take comfort and solace and escape where we can. Art plays a really important role in that. This is not a real city, this is not New York, but the way that Fill turned to something like a cultural and artistic product—a voice on the radio whose reality he didn’t fully know or understand—had a lot to do with when I moved to New York City and how I felt as a young person, not knowing a lot of people and finding myself at the movies and discovering great cinema, opera, and books. I think that loneliness, pain, and isolation—I don’t want to say of modern life because I’m sure it’s always been a reality—is something you can find solace for, and that can be easily exploited.

The idea in Blackfish City is that the radio broadcast, “City Without a Map,” is this benevolent product that is being used to unite people for a positive purpose and to give people identity and hope, and connectivity. Versus in The Blade Between, it’s a malevolent tricking of people, exploiting people, and getting them to do things that might not be in their interest but suits the agenda of the folks doing it. So I think life is hard and we make tough decisions as a result and that can take us down some strange roads.

Both books have employees in the city system working outside it to protect citizens from landlords raising rents. How do their actions support the line “All cities are science experiments”?

I think that cities are many things. They are science experiments—they’re highly structured and they’re also completely structureless and chaotic. Everyone is trying to navigate them the best they can. Often people gravitate toward public service because they care about people and they want to help people, so they often end up in positions working for governments. While the purpose of government in the abstract might be to help people, I think that in reality, governments function mostly as a way to maintain the status quo. If it’s a great status quo, that’s great, and if it’s a terrible status quo, that’s terrible.

While a lot of times people gravitate towards government work thinking they can help people, often they find that that’s not actually the case. It’s actually very difficult to help people. There are a lot of systems in place to keep people from creating change, and that often means they have to go outside of those systems and give people things that they shouldn’t be giving them to support them. They may have to tell people, “I shouldn’t be telling you this, but you should do this.” That’s been my experience as a community organizer, working with folks in government or who work for city agencies, and just in terms of being a person and looking around and seeing how people function. There’s the way I’m supposed to do things and then there are other things that I have the power to do. That is a small way that I can struggle to make a change.

Your work represents how we have a society at the loss of community and in doing so we are not taking care of all of our citizens. To make that point, you show the harsh realities of today and the path we are on for tomorrow. Do you wish to discuss elements of your work that some readers might find triggering?

A lot of the reason that I’m a writer is that I want to tell difficult stories and help myself better understand a lot of the problems that I see in the world, and that involves often going to some scary places. I know that people will often be triggered by stuff that I write and I don’t want that, but I also trust readers to be able to take themselves out of it, which is what I do as a reader. If I see a content warning around a certain subject, that doesn’t mean I’m not going to read it, even if it’s something that I find triggering. I’m going to read it until I have to take myself out of it. The fact that it deals with something that I personally find really difficult to read doesn’t mean that it’s going to be handled in a way that’s exploitative or that I’m going to personally find triggering.

It’s happened that I’ve written a story where at the end of it, I’m like, “Oh, I wanted to understand this horrific thing and in writing this story, I understood it too well. I don’t want anyone to read this, so I will not be putting it out into the world.” But generally, I try to proceed with as much respect and caution to avoid the things that I personally find triggering, like when something is reveling in the details or trying to manipulate an oppressive, violent, or traumatic thing for the point of manipulating the reader’s emotions. Those are the things I try to avoid. But I respect that everyone’s different and what I find triggering won’t be what someone else finds triggering. So unless I’m only going to write about things that are not super interesting to me, I have to imagine that triggering is a possibility and that I’m going to do my best to be as careful and respectful as I can with that topic.

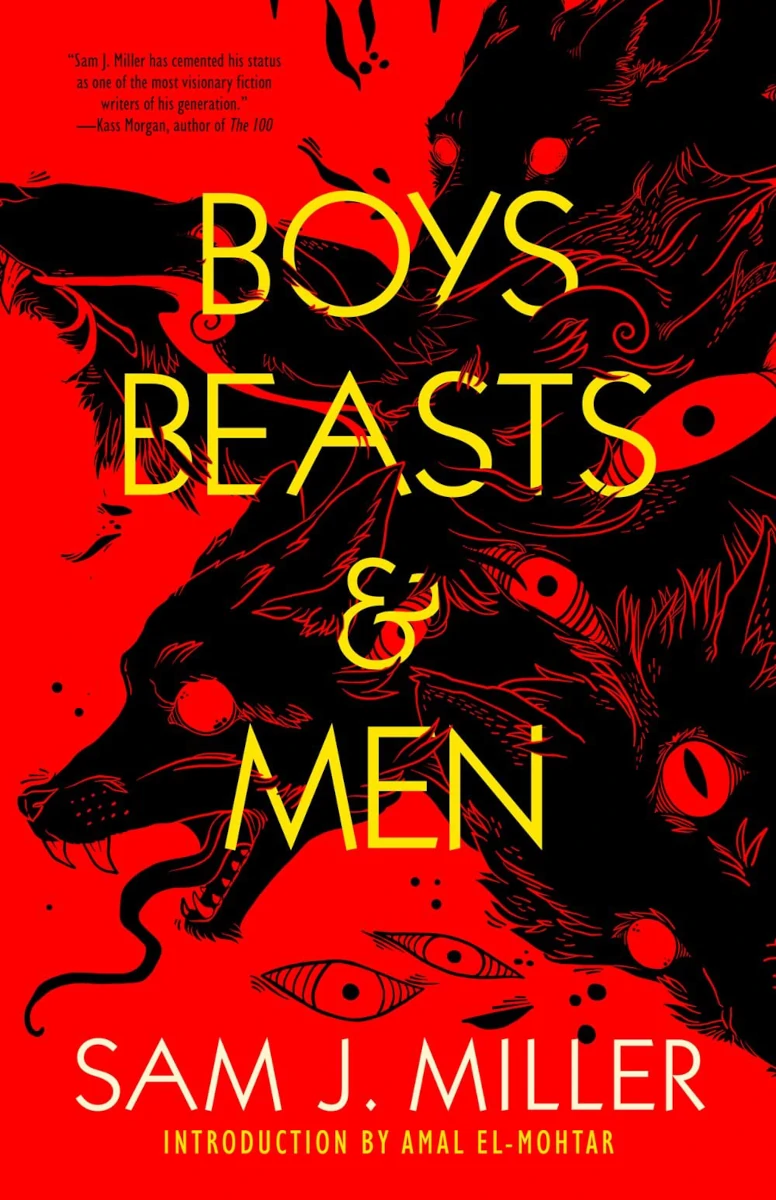

A draw for me for your work was how you write about masculinity. Tell us about your new book Boys, Beasts and Men from Tachyon.

I’ve always wanted to do a short story collection. I love short stories and I love writing them. They’re so special and different from novels. I realized as I was working on this collection and gathering these stories together that it really emerged as the idea of masculinity as this constant obsession of mine. What does it mean to be a male person in a patriarchal world and in a world where toxic masculinity is a reality? This is the iteration that I came up against again and again. If you’re a male person, whether you’re cis or trans or anything, how do you inhabit that identity in a way that’s not violent, oppressive, or toxic? That’s a constant work in progress. There’s always going to be things popping up. Socialization is so deep and our exposure to problematic aspects of maleness and male relationships is always evolving and changing. Even if you are really good in some ways, you might be really terrible in others. This collection is constantly reevaluating that. It’s not that I’m only interested in male characters—many of the stories in the collection are narrated by women—but that complicated thing of monstrosity and how easily toxic masculinity can make people monsters.

Your short story “The Heat of Us” put me at the night of the Stonewall Riot. Can you talk about finding a place to develop yourself around others, like at the Clarion workshop where you worked on the story?

That story is very much about Clarion. It’s about the experience of being in a cohort with seventeen other writers from many different backgrounds and life experiences and coming together to discover how awesome we are, how we help each other, and how we make each other better. Someone once said the spoiler alert to every Sam J. Miller story is collective action—people coming together is the thing that makes the difference. This short story is very much that. I had been a community organizer for eight years at the point, so in theory, I should have already known that being in a community with others can give you superpowers, but I hadn’t applied it to my writing before. So while it’s very much a story about Stonewall and about resistance and activism, it’s also a story about creative collectivity.

Some of your stories are Bradbury-esque in that they share a love of classic film stars. Ray Bradbury also wrote about his ideal hometown life in Dandelion Wine. Can you talk about how your work helps us know and face the monsters in the world while having a love/hate relationship with our hometowns?

I am obsessed with Ray Bradbury. He was my first love as a science fiction reader. The thing that I love most about Ray Bradbury, and the lesson that I’ve tried to learn from him, is that he’s always having fun. He’s writing about dinosaurs and King Kong. He’s writing about aliens, Martians, and spaceships. He’s not always writing about those things, and there is the more lyrical stuff like Dandelion Wine, but writing about what sets you on fire is his lesson to me and what I try to carry forward. I think that that pops up in so many ways in my fiction. I hadn’t really thought about Ray Bradbury’s shadow over my hometown in The Blade Between, but it’s very there, along with the magic of childhood and the way he captures that. When you’re a kid monsters are real. The werewolves are real and the dinosaurs are just around the corner. Everything is possible to a child’s brain.

When I was a kid, I really loved my hometown. It wasn’t until I hit puberty, started getting bullied and had to grapple with what it meant to be a queer person in a very homophobic small town. I am definitely channeling that dichotomy with this book. There’s the magic of it and the way you’re going to love it even if you hate it. Even if later in life you change into a person who can’t actually be there, that magic is still going to be there. Ray Bradbury taps into that really well. I hope I can do likewise by showing that complication—the world is magic and the world is wonderful, but the world is terrible, and how do we make our way in both worlds?

Where can our readers find you?

My website samjmiller.com has links to a lot of my short stories. I’m on Twitter way too much. My Twitter handle is @sentencebender. I love photography, so I’m also on Instagram way too much. My Instragram handle is @sam.j.miller.