An Interview with Nate Ragolia

Words By Dani Hedlund

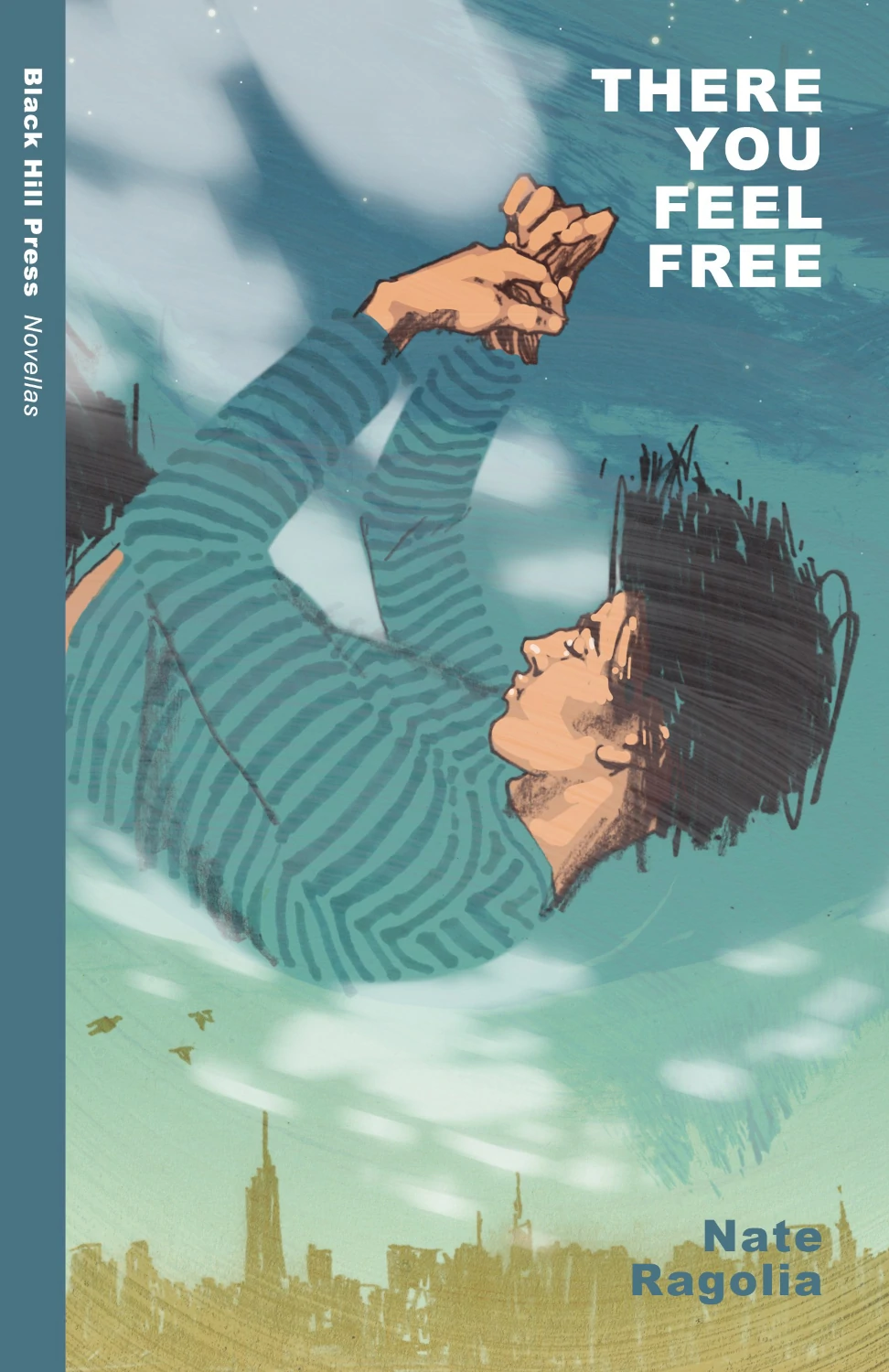

Where did the idea for the ridiculous form of your novella There You Feel Free originate?

It came in part from my publisher. The long story is: I wrote the poem for NaNoWrimo in 2011. My girlfriend (now wife) had done a hipster-ized re-write of The Sun Also Rises. I didn’t feel like tackling a whole novel so I decided to go after T.S. Elliot’s The Waste Land. I saw parallels in the content, like the wasteland of disillusioned youth, a theme that many people find prevalent in There You Feel Free. I wrote this poem and in the reaching out I shared a couple of the manuscripts. The gal who ended up being my editor, Marisa Roemer, latched onto it and said, “This is amazing, what can we do to make it longer?” We brainstormed about David Foster Wallace and Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov. This concept emerged, and she said, “Go write and get your manuscript back to me in three or four months.” I spent that summer cranking it out and seeing what I could do, trying to attach meaning to the ends of love and various stories from my life. I did what a lot of us do—I repurposed the things that have happened to me.

What was that experience like? Did you ever feel like you were diluting the original poem by having to extend it, or did you feel like the process was natural?

To be honest, I felt like I made it better. The poem on its own functions well as an eye-patched pastiche parody; it’s goofy and it’s kind of silly. As I continued writing, I realized that I became more and more earnest because I became more and more attached to what I was trying to do. It was never about contemporizing the content—instead, I wanted to connect meanings. I think that’s the reason why the fiction in the endnotes really means something to me. It adds a modern context to a poet, to T.S. Elliot.

A lot of young people, and a lot of people in general, think that poetry is this form couched in an era; it doesn’t apply to real life; it doesn’t apply to the present. I felt especially with this subject, Elliot’s work applies to the present more than the work of many other poets. The Waste Land and The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock are two of Elliot’s poems that really do apply to the present day. When you talk about people chasing after their own meaning in life and not finding it, only to realize they must find it elsewhere, that’s timeless. I added the stories because I wanted to make my piece timeless; I wanted to ask people to connect on a whole new level and maybe laugh along the way. Poetry can be fun, interesting, and playful. It’s designed to be a conversation driven by creativity, not necessarily the vestiges of Oxford.

There You Feel Free does an exceptional job of balancing open satire with an incredible amount of honesty, and the ability to impact the reader in a way that feels real. How did you walk that line?

T.S. Elliot invokes a lot of Greek mythology and other mythology to elevate the discourse of his poem. I wanted to invoke the inverse, so I pulled musicians, references to actors, and I allowed myself to comment. I put my Pitchfork Media hat on and I thought, what would a really pretentious person do with this reference? And then, what would a regular person do with this reference? I figured out what works and what doesn’t. The best kind of comedy and the best kind of thoughtful work is always loving, not cruel, even when there are a lot of mean things available to be said.

I understood many of the literary references you make in the text, but there are plenty of references that I didn’t understand. This sort of alienated me from the prose in the same way that I don’t feel “cool” enough to be a hipster. Is the pervading “hipster feeling” intentional?

I always try to remain accessible. I view writing as a form in which the author is aware of the audience without having to talk down. My favorite reading experience is one in which I have to set aside the book and look something up. We live in an era where the dictionary is on our phone and searching for these kinds of references is made easier. Part of the joy of reading an author like Thomas Pynchon is you get to look stuff up, but part of the alienation is that you must. Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, for example, is a very tiring reading experience. I’m glad that I was able to create something that is in between. My book is about alienation, it is about the sense of self and where it comes from, how we find it. In a modern era where everything is packaged and individual branding is pertinent to one’s image, these things become increasingly important. People don’t hug each other freely and have earnest conversations anymore. The “clippiest” version of yourself becomes the only “self.” I’m guilty of it too, I participate on Twitter frequently, Facebook, and I market myself.

You address this in the book, but tell our readers a bit more about how the themes of alienation and unity in Elliot’s work come to life—specifically, in the lens of social media?

The third section of the book, the section of end notes attached to the third canto, is about this guy named Doug who spends his life sitting around, checking Facebook, looking for validation through likes and through any of the cheap, easy ways that we seek admiration, affection, and validation these days. Doug reminds us that we are rapidly drifting away from self-sufficiency. I was born in 1981, so I do remember a time where I didn’t have a cell phone until my junior year of college. I had a landline for years and I had to run home to receive a call. I would sprint home after work or after class just to check the answering machine. You had to wait. It cultivated a patience in people and a sense of self-assurance. I was once able to stand around in public and have nothing to do. Granted, I smoked cigarettes and that was my proxy. We’re inundated with information and that can be good but it also prevents us from formulating ourselves, independent of everyone else.

Before you were encouraged to expand this poem, did you identify more as a poet or a prose writer? Did the footnote sections come easier to you than the actual poem?

I identify as a prose writer, I think my poetry is generally garbage. I would liken it to the works of mid-level post-second album Jewel, the sophomore slump Jewel. However, writing the poem was extremely rewarding. I put a lot of effort into maintaining the measure and the scheme. I found that the prose was easier to write because a lot of it consisted of a ten-year brain dump of things that happened to me, that I had witnessed and that I had been around. I was able to tap into these experiences all at once so it did flow very easily. I also have a hard time being as concise as I need to be in a poem. To be perfectly honest, I second guess myself in a short form work. I could probably write a fifteen-line poem and spend six years trying to figure out exactly how all the words fit together. It’s an incredible skill. I have a couple of friends who are exceptional poets, that can capture a place, a feeling, a moment in five lines without ever saying any of those things aloud or directly. It’s dazzling.

We talked about you writing this piece in NaNoWrimo and then your involvement with Black Hill Press. Where did you query for publication and what was your publication route like?

I lucked into having a friend, who was friends with the friend of the guy who started Black Hill Press. It was all luck. I queried my butt off with other manuscripts and got nowhere. The whole process was good because my editors liked the poem, they believed in the idea, they let me run with it, and then we did four rounds of edits and revisions. It was a good mix of additions and cutting.

From the first word on the page to seeing it in print, how long did the process take?

About a year. Black Hill Press and the nonprofit that umbrellas over the center is small, they’re new but they move quickly because of that. Of course, as a first-time publication, I wanted it faster.

What do you think is the one thing you wanted to say with There You Feel Free?

We are not doomed, we are more powerful than we think we are, and things will work out. I say this because I think there is a lot of doom and gloom in society now. We are so attached to tragedy. As a person who is now in his mid-thirties, I can look back at my twenties and see that I worried a lot about stuff that I ended up discovering myself. Maybe that’s what it’s really about; you’re going to worry about a lot of stuff, many things will go wrong but if you try, you are going to discover yourself.

Given your mission statement, do you think you have accomplished it with your book?

I hope so. I think my book is about finding love, about finding yourself, trying to get away from the things that pull you away from being grounded, and the beautiful honesty that is being able to sit in silence and think without judging yourself. For me, my success equates to the conversations I’ve had, just having this interview means a lot. It’s not about money at all. I think of myself and my work as a catalyst for conversation but when nobody responds, I find it devastating in the same way you might walk up to somebody on the street and ask them out. Being shut down is a tough thing. But through all of this—learning, rejection, conversation, growth—the bottom line is: you have to find yourself.