An Interview with Mark Waid

Words By Mark Waid, Interviewed by Dominic Loise

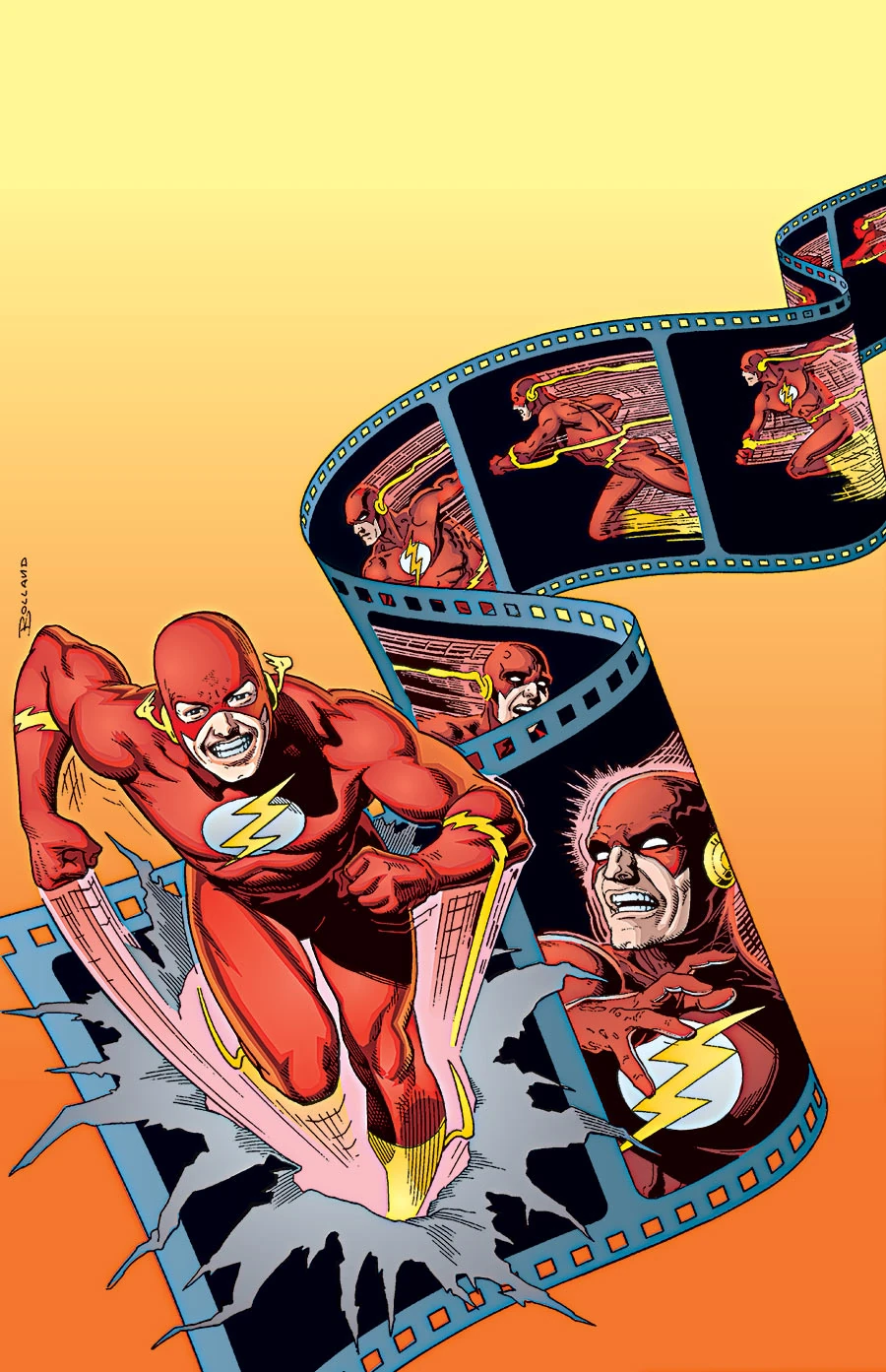

Flash: The Return of Barry Allen storyline just celebrated a twenty-year anniversary in 2023. Decades later, it still stands out to me as a story of Wally West dealing with/overcoming imposter syndrome, where, though someone might be high functioning in their role, external circumstances could cause them to still feel phony and doubt themselves or their abilities. Where was Wally at in his life when you took over writing this storyline in the nineties?

As a fictional character, he was actually in a good place; my predecessor, Bill Loebs, is an excellent writer who brilliantly communicates his humanism through his work. As a comics series, not so much. It wasn’t not selling, but sales were sliding in the wake of the year-long bump the recently canceled CBS-TV show had given it. At a Christmas party, right after I’d taken the book over, a drunk DC executive said to me, “I don’t even know why we’re bothering to publish that book now,” which if anything only made me double down on my efforts.

To give our readers some context, can you talk about Barry Allen, the previous Flash, saving the entire DC Universe during the original maxi series? And how his sacrifice was considered untouchable, as far as bringing Barry back, in an industry where characters are regularly resurrected?

In short, as much as that can be: While there had been one or two parallel-world stories in DC comics before Barry Allen was introduced, in DC continuity he was the first superhero to discover the concept of alternate Earths, and a lot of his stories revolved around the concept. But by 1986, DC was interested in streamlining its continuity by eliminating the multiverse—hence, the Crisis on Infinite Earths series—and from a meta standpoint, just as Barry had been the one to open the multiversal door, he was killed off in the story that closed it. And it was, by all standards, a well-done and moving death with a solid sense of finality about it. (This was before the trend of killing-and-reviving characters was so common that comics Heaven installed a revolving door.) On top of all of that, through managerial errors less than the writer’s doing, the Flash series had been duller than dishwater for nearly a decade prior, and Barry was always portrayed as a good guy with all the depth of a bottle cap. So, his sacrifice was probably the best Flash story told in years and years. Consequently, there was real resistance to ever resurrecting him. So great was his sacrifice, he became DC’s first unofficial saint. And on top of that, his nephew and former sidekick, Wally West, took up the mantle in his honor, and that worked out so well no one wanted to take that away from Wally for the longest time.

Your first, ongoing Wally West story in The Flash series, dealt with him as Kid Flash and gave readers a look into his safe space of visiting his Aunt Iris (Barry’s girlfriend and future wife). How did this time with Iris and Barry impact Wally’s time away from his home life? How would Wally’s relationship with his Uncle Barry, not just Barry as The Flash, create a situation where he would find replacing Barry unimaginable?

You know what? I’ve never once thought about that. Nearly every time we ever saw the two of them together, they were superheroing, so I never really imagined they had a strong familial relationship out of costume!

The very first issue of The Return of Barry Allen, Wally talks about his inner conflict of wanting to honor Barry’s memory by being The Flash but feeling he is not up to the task. At the time in comics, how groundbreaking was it that Wally was the first ever sidekick to take over the mantle of their mentor?

Hugely. That had never been done before, and it made Wally unique in the superhero pantheon. It’s been done plenty since, but Wally was the first to take over the identity of his mentor.

The Return of Barry Allen also deals with the physical manifestation of Wally’s imposter syndrome, namely that he can only run at the speed of sound following Barry’s death. Can you talk about how the Flash family gets Wally to address the issue and how it ties into his fear of surpassing Barry when running at his top speed?

Wally’s limitations—chief among them, that he wasn’t nearly as fast as his uncle ever was—were certainly mentally imposed. That disparity in speed wasn’t there when Wally was Kid Flash. And even though Wally knew that intellectually, he couldn’t break through that barrier emotionally, where it counted, until Barry’s reputation was in danger of being permanently blackened.

There was a surprise outcome from this storyline. I don’t wish to talk about the ending for fear of spoiling the story, but can we discuss how The Flash comic became a beacon to guide the industry out of its “grim and gritty” era? Would you like to talk about the heroic age that followed this time of darker superhero stories and Wally’s part in connecting the whole DC Universe together?

Editor Brian Augustyn and I shared a deep admiration for what were in the 1990s considered “old school” comics—comics where heroes saved the day because they were clever and had heart rather than because they could punch villains really hard. And I cannot overstate how absent that storytelling approach was from the comics medium in that era. It was a time of dark, cynical storylines and events, and neither Brian nor I had any use for cynicism. To us, cynicism was utterly antithetical to the very concept of superheroes, who were adolescent power fantasies created to do impossible things. Consequently, Brian and I and our book were looked upon as a throwback to the Silver Age of comics, and it took readers a l-o-n-g time to realize that, no, we weren’t trying to replicate the comics of our youth; we were trying to take the best parts of them and fold them into modern stories with modern storytelling. And we can thank writer Grant Morrison as much as anyone for pushing that idea. His open acknowledgement of how what we were doing was direct inspiration for his own DC superhero work was just the endorsement we needed. Slowly, we began to push the overall tide back towards a sense of optimism.

When you later returned to writing The Flash comic in the aughts, you showed Wally as both a superhero and family man with two kids. Can you talk about how being a father to Iris and Jai West shows Wally moving beyond the broken home that drew him to run in the footsteps of Barry and how he now walks his own path as The Flash?

Giving him children wasn’t my choice and was probably not a choice I’d have made, but my job when taking on a series is to play the cards I’m dealt, so I made an effort to, in fact, contrast his own painful upbringing with the happy home he gave his wife and kids.

Was there ever a time that you dealt with imposter syndrome as you started writing comics and began working on characters that were iconic from your childhood?

Christ, what time is it now? I still feel it. Find me any writer who doesn’t deal with imposter syndrome, and I’ll show you an overconfident hack whose work isn’t nearly as good as they think it is. Honestly, I consider imposter syndrome part of the writing equation, as a hell of a motivator to keep trying and keep inventing new techniques and new ideas.

What was it like writing a teenage Wally Kid Flash?

Fun! We sidestepped some of the ugliness of his life at that period, but honestly, the Wests weren’t monsters, and in my mind, it’s not like Wally suffered every day at their hands. The family simply flared with dysfunction frequently, and in that issue of WF: TT, we were lucky enough to be there on one of the good days.

What are you working on now and where can our readers find you online?

Currently, I’m working on DC’s Batman/Superman: World’s Finest and (issue two coming soon!), as well as their summer event series, Absolute Power. There are also a few other assignments in various states of completion that DC will be announcing soon.

Online, I’m on Bluesky and Instagram (the latter as @waidmark), and because I’m old, also on Facebook. I don’t update markwaid.com as often as I ought to, but that’s also a part of my online presence.