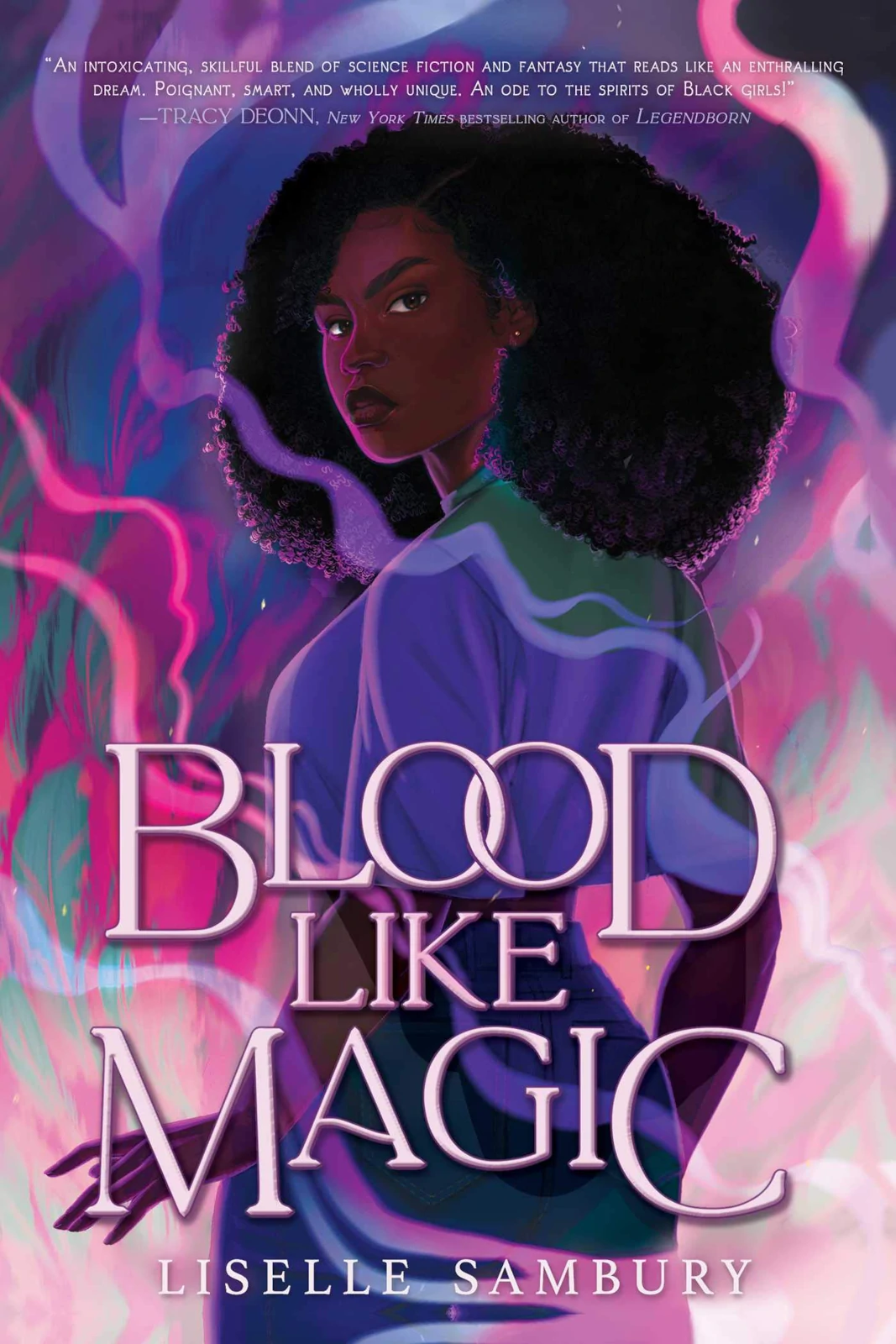

An Interview with Liselle Sambury

Words By Liselle Sambury, interviewed by Dani Hedlund

What inspired Blood Like Magic?

I had this image of a girl in a bath of blood. At the same time, I wanted to write a story about a family of black witches. It was NaNoWriMo 2017—and I started with a different project—but this idea, this family of black witches, kept poking at me. So, I started writing and spur of the moment, I decided to set it in the future, just because I thought it would be fun. I ended up discovery-writing a lot of this book. I started with the girl in the bath of blood, and I had to figure out why she was there. A lot of things I came up with off the top of my head because I thought they’d be cool, and I built the magic system along the way. A huge part of the story was missing Toronto and wanting to explore the city where I grew up. It combined my desire to get lost in and feel nostalgic about my city and then this little niggling desire to write about this family of black witches.

I don’t really know how to describe the genre of this book. It’s fantasy, it’s sci-fi, and there’s also this very intense historical-political view of the family tracing back their legacy. What was it like to smash that many genres together?

The fantasy and the sci-fi bits were conscious decisions. I wanted it to have both, but I was terrified that I would submit it to an agent, and they would want to cut the sci-fi. I made sure that the witch community relied on the sci-fi aspects of the book and that the reverse was also true. The historical bit was just something I wanted to do, but it also came up naturally when I got into the magic coming from ancestors. I had to think about who the ancestors were and where they might be from.

I had to understand the struggles of the past to understand not only the present but how that would affect the future. In the book, you have these ancestors who you not only have access to, but they’re also trying to affect your present. They have their own ideas about how you should be conducting family and living your life; they’re asserting those on you, while also having the ability to look into the future. They’re deciding what they’re going to tell you or not tell you. Everything is a test to make sure that you’re worthy of this magic that you’re getting. And I not only had to reconcile with my own history but also with how history is relevant to the world today. I ended up talking to family members about where we came from, and how my family came to be in Trinidad and Tobago and in Canada. I also read The Book of Negroes by Lawrence Hill, which was wonderful. That reconciliation is a big struggle that Voya goes through because she feels so disconnected from this ancestor who is insisting, “I’ve picked you because I think we have something in common,” and Voya is very much like, “I have absolutely no idea what you think we have in common.”

Where did the idea of pure magic and impure magic and the political system around it come from?

I have always loved the idea of a gray area, of people who are not purely good or purely bad. I like making people grapple with an idea that on paper seems like a terrible thing that could be used for good, which is the thing about impure magic: you have to torture and or kill someone to get that magic. But you have to have a pure intent to do it. Impure witches have done dark things, but they’re the only members of the community with the magic to actually do good and to actually make a difference. The pure witches have moral superiority, which becomes difficult for Voya when she gets is tasked to kill her first love. That’s an impure act, and her family has raised her with the idea that they are morally superior, that this is not a thing they do anymore, and that they are ushering their family into this better age of magic, even though their gifts are weaker. And that’s another component to pure magic: you’re supposed to be the good guy, but you’re also suffering because you don’t have the same sort of power. You can’t afford the same privileges because you don’t have enough magic.

I’ve always been so fascinated by making people struggle to think oh, well, this person is just like, all bad, or this person is all good. Voya’s family is also kind of like, maybe you should kill just this person, and that’s okay. Whereas Voya’s very much like, no, you told me not to kill anyone and now you’re changing things. The plot started from a desire to have these two factions, where both are in a gray area, and then make them have a complicated relationship as they’re dealing with the hypocrisy of saying: Oh, these people are bad. But we’ll make an exception for these people because they’re technically part of our family. But we won’t make the same exception for someone else.

Did you intend to toss up the typical YA romance model, or did it come naturally out of putting together your plot elements? Where did the central plot of killing your first love come from?

I love stakes where you have to do extreme things for love. In a lot of books, it’s killing someone else to save the love interest. I was curious about situations where you are supposed to kill the person you’re supposed to love, and you’re having to make this choice between family and between this love interest. I wanted to see how that would play out. But then I had to think, well, she would do anything for her family, right? And so that’s where the family came in with them being very against doing this thing. So then I had to create struggles for her, and I had to make this a boy that she needed to love because that made the struggle deeper. It wasn’t like she was just killing a stranger or a friend, you have to go through the entire process of falling in love with someone. So those feelings are so fresh, and that’s when you have to do this terrible thing. I started with the stakes, and then I was like, how can I make this worse?

Blood Like Magic involves genetic compatibility. What was it like to break down relationships to core levels? And how did you go about exploring that?

It was difficult because I love an enemies-to-lovers trope, so I knew I was going to do that from the start. But then I had to think about the genetic basis for everything. There had to be some sort of drawing together, and for Voya, whatever genetic basis there is is obliterated by the fact that she’s like, well, I have to do this task, so I have to hang out with you and I have to fall in love with you. Whereas on Luc’s end, it’s very different. Luc is disinterested in the whole thing, he’s very focused on his career, he’s very focused on getting ahead. But he also has a great deal of self-consciousness about whether people authentically like him because he’s the adopted son of a very rich man who owns the company he works at. He’s frequently dealing with people that are putting on fake smiles, and he’s also very much grappling with the idea of, well, people don’t like me and that’s okay because I’m grumpy now and I don’t like them either. That was kind of the dynamic I had to work with. Even though they fully understand this genetic basis of love, you still have to create the trappings of general romantic conflict and have them be distracted by that so that they can start to forget the genetic component that says, hey, you’re supposed to like each other.

Intimacy is a common theme in the book, especially with Voya having a best friend who can read her mind. What was it like to build conflict and secrets in a world where you can hide almost nothing?

It was definitely part of the discovery-writing process. If Keis can read everyone’s mind, she’ll know everything. So I knew there had to be some kind of challenge and that’s where the element of dwindling magic came in. Then I had to go back and build everything around dwindling magic so it made sense. I also rebuilt Keisha’s character and make her kind of bad at it. She became a person who doesn’t want to be defined by magic and doesn’t want to use it. She’s doing everything she can to not be good at this very amazing skill she has. She’s a pretty stubborn person, but she has to have some outlet, which helped make her and Voya’s relationship closer. Voya is her outlet. Voya is the one person whose mind Keis very specifically focuses on to help her deal with everything. But that also created complications because now you have your best friend that can pay attention to your thoughts whenever they want and Keis has to ignore Voya’s embarrassing thoughts or things she doesn’t want to talk about. So the logistics were difficult to think about, especially because of how it also affects Voya. Voya relies on the mind-reading to enable bad habits, like making Keis help her make decisions or avoid confrontations by making Keis handle it because Keis is more stubborn and straightforward.

What is the largest change between your very first draft and the published version?

Probably the genetic matchmaking system because I rewrote it two separate times. I wrote half of the book with a mentor through a mentorship program to fix the matchmaking program. Then I wrote half of the book, again, with my agent to fix it again. That was definitely the biggest hurdle because, in the original version, it was structured by the company. Luc and Voya had to come in from this initial meeting, they had to do these checkups, they had enforced dates that they had to go on. But then I added more dates because there weren’t enough dates, and then my agent brought up a very legitimate suggestion: would they do this in the future? Right now, you just go on an app and you swipe and you go with your person. You don’t have to do all of this rigmarole. So I changed it to them getting an alert on their phone saying, this is your match, here you go, come to make sure you put a monitor on so we can track your metrics, and otherwise, do as you please. This ended up being for the best because it forced Voya to have to be the one to go out and make these dates happen. It made her a much more active character because she had to very actively pursue someone who also did not want to be pursued. It also gave Luc an excuse to not participate so that she had to push even harder to make sure he would go along with it.

What was the most fun moment to write?

There were a bunch of things that were fun. I love the scene at Brown Bear, the gaming cafe where they have to rescue Keisha from her bad date. But they’re also using it to blackmail her into helping them find information. I love it because Keis’s very upset to be there and because it’s got a little bit of a gruesome element in there. I love it because it’s also the first time that Keis and Keisha—who are sisters but are always very much at odds with each other—have a positive sisterly moment and Keisha gets to talk more about her identity and being demi-romantic. It’s a scene where a lot of things happen. But it felt really fun to write and I always have a lot of fun when I write Keisha because she’s so ridiculous.

What was your process of becoming a writer like?

I started writing as an emotional outlet at thirteen. I wrote out stories that were already in my head and I would feel better. Writing made me forget about my feelings or what happened at school. When I got to high school there was a writing club, but I was too intimidated to join as a freshman. I finally joined when I was fifteen and that really built my confidence as a writer. I was sharing my work with people for the first time, and to my shock and glee, they were enjoying what I was sharing. I realized I wasn’t half bad at writing and I was getting feedback on how to improve. So I stuck with the club through high school and even became the head of the club as a senior. Then I went to university, where I queried a Twilight knockoff and realized how difficult querying is. In my third year, I was accepted to an application-only writing class. I wrote literary short fiction then because that’s what everyone else was doing. After getting out of university I did one more year of college and then I started a desk job. That job gave me so much free time that I got back into reading, started book blogging, and then started working on my second novel. I ended up shelving that second book and then went on to write Blood Like Magic.

What do you think is the one thing that you really want to say with this book?

Black girls can be heroes too. When I was growing up, books like Legendborn and The Gilded Ones, books that show black girls can be the main character of the story, that they can have the love story, that they can go on the quest, that they can save people, and that they can be the hero didn’t exist. That elimination of the single narrative was a big part of what I wanted with this book. I wanted to know that I could put it out there, and a black girl could pick it up and feel included and not feel like there wasn’t any book for her. When I was growing up, I had to suspend disbelief, I had to push myself into a character that really didn’t have me in mind. I had to deal with the only representations being stereotypical or problematic in some way, or not making me feel great, or like I could ever be the main character of the story. I want there to be all these different representations, where you can think I want to read an urban fantasy with a black character and be like, oh, there it is.