An Interview with Lev Grossman

Words By Lev Grossman, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

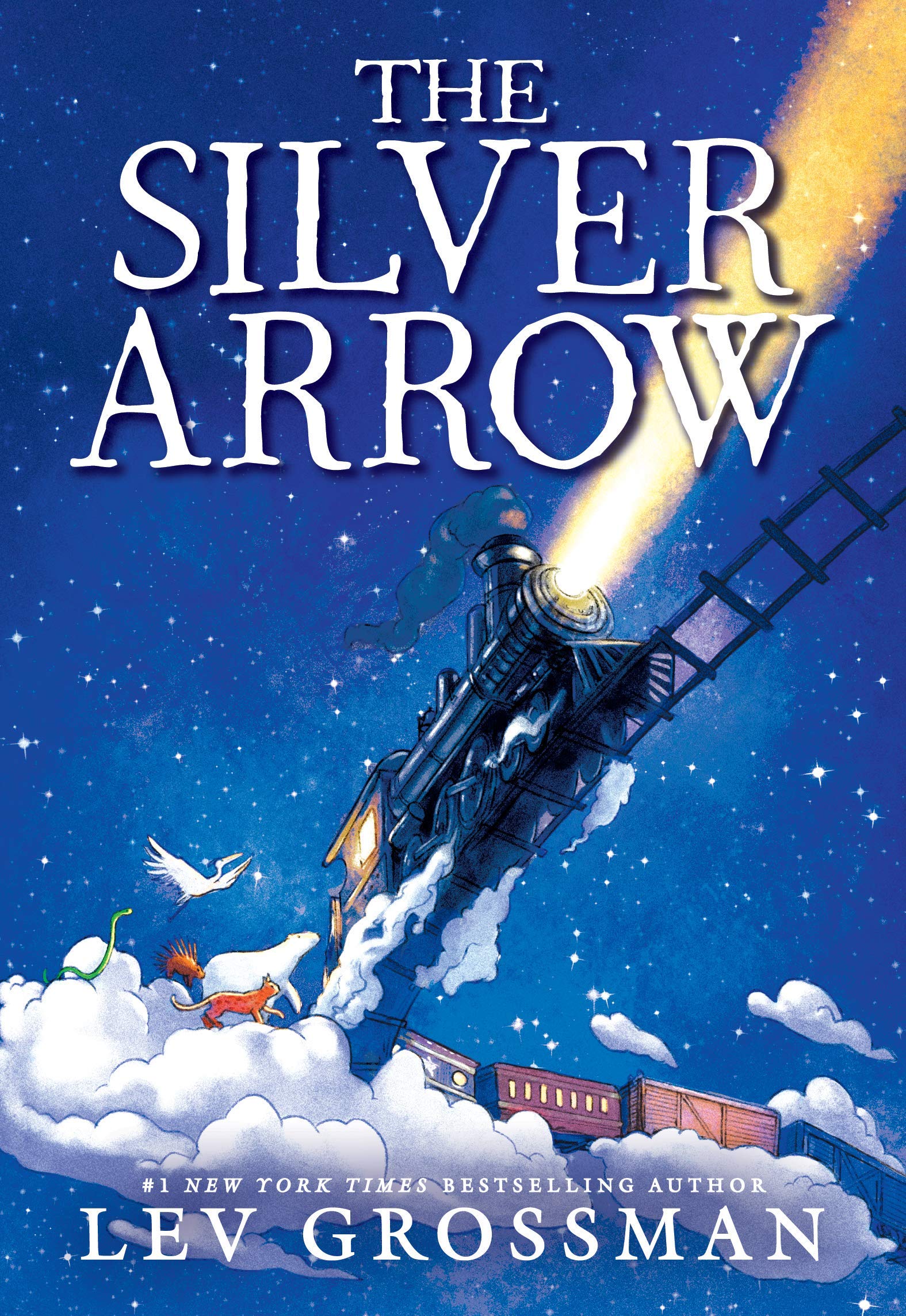

Dani Hedlund: Okay, most cliché question on the planet: Lev, where did the inspiration for your new book, The Silver Arrow, come from?

Lev Grossman: I never know where it comes from until people ask me and I’m standing in front of an audience and suddenly it hits me. I think this book started with T. S. Elliot and Skimbleshanks: The Railway Cat. There is an incredible description of the railway car that Skimbleshanks takes. It has this little basin and this little fan and you sort of snuggle down in your little nest. That gave rise to this image of a young girl on a train moving through a nighttime landscape. She’s looking out the window in this plush sleeper car that she’s in, and there’s no one else on the train.

What was it like transitioning from your very serious novels and sex-drenched magicians to a children’s book?

It wasn’t as big a deal as you would think because when I wrote The Magicians I could actually still remember what it was like to be in my twenties, to be single, and drinking all the time. My life has moved farther away from that world. And now I spend a lot of my time—especially in quarantine—being a dad and using that dad voice. So this is much closer to my world now than The Magicians is, and it feels very natural. I tell stories to my children. I was ready to write a book for kids.

I found it interesting that this voice interjects to teach the kids valuable things. What was it like to balance the plot with these miniature lessons?

The lessons that children need to learn turn out to be the lessons that adults need to learn. It’s not any different. We just spend our whole lives learning these particular lessons about being responsible and having empathy and things like that. You want to write the book that you wish you’d read as a child. And you always remember the bits in the books where the author imparted the parental wisdom because those parts sucked. You didn’t feel it or absorb it because it was so boring. So even though I wanted stuff like that to be in this book, I tried to incorporate it in such a way that maybe readers would feel beyond just hearing my voice and feeling like I was teaching a lesson. Nobody likes lessons, but you can’t get around them.

I’ve got to ask: did you just know everything about nearly-extinct animals, or was this a lot of research?

I did do a lot of research about animals, and about trains, once I had zeroed in on certain animals that were part of the dramatis personae. The internet is not always a great place to be, but it was great for really granular information about animals.

Was there equally good information about trains?

I don’t know how current a member of the steamer train community you are on the internet, but there is always someone who knows ten times as much about steam trains as you. They didn’t have computers back then, so they had to nerd out on something and they nerded out on steam trains. It’s unbelievable how complex those things are—they’re really magnificent.

There is a conservation aspect to this book. Where did that come from? Where did the image of this young girl looking out at this plush land from the train move into this other angle?

The short answer is, I couldn’t get around it. I definitely didn’t set out to write some sort of ecological, political screed. But I was picturing this girl on the train, and where the train is going. Several months later, I saw the train going through a forest and I saw the light up ahead—it was all very Narnian. The train reached a station in the middle of the forest and there were animals waiting for it. And what do the animals say? What do they talk about? And it’s not Mr. and Mrs. Beaver. The animals, they have very complicated feelings. It’s not like, “the humans have come to save the day, hooray, at last they’re here.” The humans have been destroying the world. And now the animals have the chance to actually talk to the humans and they have a lot to say about what’s going on. I was trying to imagine that conversation. What else would they talk about? It’s the elephant in the room and sooner or later it’s got to come out.

The section where the animals have something to say about that was miraculous. It could have been preachy and self-righteous, and instead, it felt really empowering.

There was a lot of feeling that went into the message. I still, to this day, cannot read it aloud. I can’t read parts of it out loud because I get too emotional.

That section felt so human, so honest in a way that we don’t see anymore. I’m really impressed with how you pulled it off.

I was writing it while trying to imagine someone reading it who doesn’t believe climate change is real, someone who is offended and angered by the suggestion that it’s real. There are millions of people who feel that way and I know I lost them when I started with pulling a polar bear out of the water. They already know that this book is coming, so they’ve stopped reading. But just on the off chance that one of them was still reading, I tried to write it in such a way that maybe they wouldn’t hurl the book across the room.

My COO was in marine conservation before she came to us, and she’s really invested in whether the next book is going to be underwater. Is it?

It’s definitely going to have underwater bits. I can’t leave the trains behind, but I promised a submarine and a submarine I will deliver.

Did you have any idea that this was going to be more than one book when you started?

I didn’t even have the idea that it was going to be one book. I’ve never started writing a novel without the feeling that I was a complete idiot doing something completely stupid. You guys were among the first to read the chapter of The Silver Arrow when it was in the magazine—it was very early on and I hadn’t even sold it to a publisher. I wasn’t sure that it was going to be a book; I wasn’t thinking about sequels at all. When Little Brown bought it, they actually suggested a series deal. But I sold it as one book. Yet now I feel like it could have a sequel. Writing sequels has to be because I can’t stop myself, not because I committed to it.

Do you feel more comfortable jumping into this universe than the universe of The Magicians? Are you going to be committed to this for a similar amount of time?

The two universes feel so different. In The Magicians there were a lot of “proxy me’s” in that universe. I felt like I had one foot in it. I actually don’t have any feet in The Silver Arrow universe. There’s not really a version of me in it. So my relationship with it feels different, though I don’t love it any less.

It’s interesting to me that you feel a stronger emotional connection reading out loud the book that you have not put yourself in.

Yeah. I think it’s probably because my children are in it. You really love your kids all the way, no matter what your feelings about yourself are. Maybe that’s why it’s so easy to love those characters—because I’m not in it.

Do you feel a different relationship with your writing now that you have kids—this other form of legacy?

I spent a lot of time as a failed writer. I think I have still spent more time as a failed writer than as a successful writer. And it wasn’t until I had children—what I imagined would be the end of my writing career—that I really began to connect with what I was writing and get something onto the page that felt authentic. Having children completely saved my writing career, because before I had them, I hadn’t really found my voice.

That’s really interesting. Why do you think they’re connected?

I was one of those people who kept a lot of emotions bottled up inside. A lot of emotions come out when you have a child. You think about your own childhood, what you were like, and you think of your parents much more because you are a parent now. You just start connecting with stuff that was frozen inside you. Writing is good for that, and having children is also very good for that. There were a lot of emotions I had been avoiding. When they came out, they got onto the page and made my writing feel more honest and deeper. People liked it more. I liked it more.

How are you balancing writing all of these books with every other thing you do? Like raising a family, writing screenplays, and not going to Comic-Cons. Are you still spinning many plates?

It’s awkward and ungraceful. This is my first book in a long time. The final Magicians book was published in 2014 and that was my last book before this. I had a lot of slow-rolling projects that were going on and on, in parallel, and now they are all coming to a head at the same time. In the middle-grade world, if you do a series, you’re really supposed to do one per year, and there’s no way I’m going to get anywhere near that. Because I have a movie coming out and I owe a young adult novel, and then I can work on the next Silver Arrow book. It’s not a graceful balancing act.

Well, what are you most excited about that’s coming out in the next couple of years?

The movie will be amazing, not because it’s an amazing movie, but because I actually wrote a movie! I can’t believe it. Then I have this book I’ve been working on for six years, which I’m very ready to have out there. It would be lovely to have another adult novel out there. I’m also working on a TV pilot. It’s a long shot that it will ever get made, but if it does happen it will be really cool. It’s like a space opera, and it would be really fun to do that.

I wish I could send this interview transcript back twenty years to show you what your life would look like.

It had been a long time since I had a book come out, and I forgot how intense the highs and lows are. I’d forgotten how sensitive I can be to criticism. Then I remembered I used to feel like that all the time. But I don’t think, hopefully, I’ll ever have to go back to that.

Whenever I feel bad about criticism, I go back to my favorite books on GoodReads. People leave the most horrible reviews. Then I just think, maybe this isn’t about me.

When I get a one-star review, I look at the one-star reviews for Mrs. Dalloway, possibly the greatest novel ever written, and I’m proud to get one-star reviews alongside it.