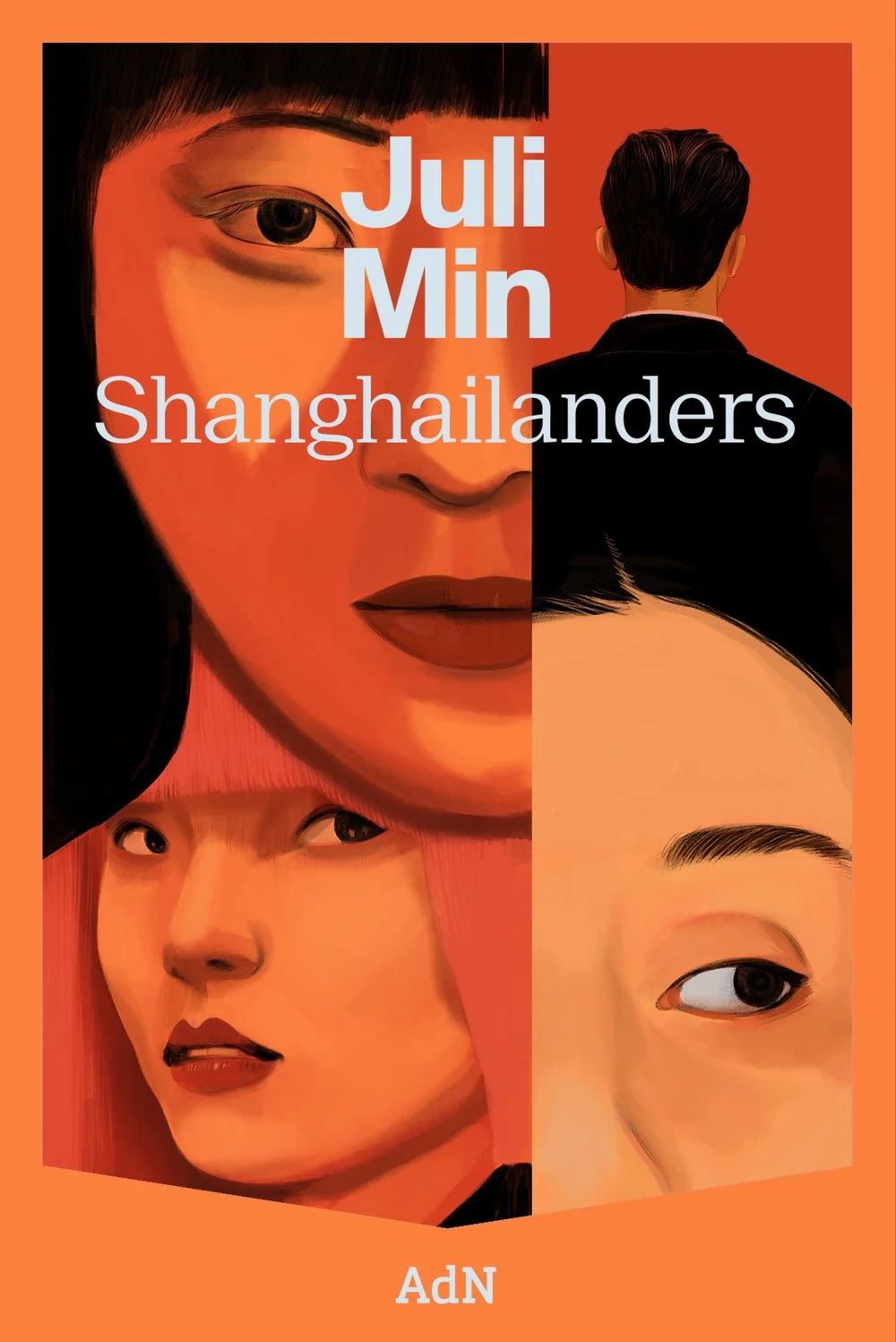

An Interview with Juli Min

Words By Juli Min, Interview by Lani McHenry

Shanghailanders unfolds in reverse, starting in 2040 and ending in 2014. What challenges went into constructing this narrative? How did it shape your understanding of the characters?

began as character sketches of various unrelated people living in contemporary Shanghai. I tried to challenge myself to make these character more cohesive. That is how characters of different races and ages were developed into recurring members of a large family. Once the relationships were created, I considered the structuring of these episodes through time. I chose a reverse narrative because I wanted to end at the beginning, creating a sense of hope, circularity, and a challenge for the reader.

It feels as though the structure happened naturally over time, each step of the writing process posing a question that the evolving structure answered.

The reverse timeline creates a poignant effect. Was this emotional resonance something you consciously aimed for, or did it emerge organically?

The final chapter takes place on Leo and Eko’s wedding day after nearly three decades of conflict in their relationship. One of the big questions for me as I wrote the book, was: do they love each other, and why do they stay together? Marriage is a dinosaur of an institution, which has survived for many reasons. Weddings are antiquated, cliché, problematic rituals that are simultaneously full of beauty and hope. I love weddings; I love love! The conflicting and complicated views I harbor lead my wanting readers to leave with a sense of love’s complex nature and what “the end” can contain and mean.

How did your experiences living in Shanghai for nearly a decade influence the way you portrayed it in Shanghailanders? Were there particular moments or places that inspired key scenes?

At least three distinct inspirations from my time in Shanghai found their way into this novel:

2021: After the birth of my second child, I stayed for two weeks in a postpartum maternity care clinic in Shanghai. My room looked out onto the neighboring lot, which was cleared for construction. There was only an old house with a tree. The house had no windows, or lights, and only one man lived there. I often looked out onto the lot, watching the man who came and went on his scooter, who often rested on a hammock hung on the branches of his tree. A character like that shows up in “Born with a Broken Heart.”

2019: While interviewing nannies, one woman broke down into tears when telling me about the little girl she previously cared for. That outburst of love and sadness touched me deeply and inspired “The Girl of My Heart.”

2018: I befriended a European woman preparing for motherhood. She had followed her spouse to Shanghai. She confessed to looking forward to motherhood, giving her life a sense of purpose. Though I knew some women felt this way, the confession shocked me. My purpose had always been writing and working. My friend’s life in Shanghai, combined with her husband’s rugged, stern look, inspired Eko. In fact, Eko and Leo in “Lane Life” were originally a white expat couple from Europe!

The Yang family’s story is deeply personal and universal. How did you balance crafting intimate family dynamics while exploring broader themes like class, privilege, and cultural identity?

There are universal human feelings and experiences—love, conflict, desire—that cross class, privilege, and cultural lines. At the same time, I hope the novel’s multi-POV structure highlights how every human being remains an unyielding mystery.

The Yang family’s multicultural background—Chinese, Japanese, French—adds complexity to their identities. How did you approach these cultural elements in the narrative?

I chose Chinese, Japanese, and French to reflect Shanghai’s historical reality. These communities have had significant influence on the city, and fluctuating degrees of power, privilege, and conflict. I wanted to represent the ever-shifting power dynamics of international Shanghai through a parallel microcosm of a family.

The novel introduces perspectives from characters who exist in the Yang family’s orbit, like the nanny and driver. What inspired you to explore these voices, and what did they allow you to reveal about the Yang’s that wouldn’t have surfaced otherwise

I hope these characters paint a full portrait of privilege: how it so often requires structural/cultural support and human labor. Human labor is often rendered invisible; I wanted to create deep and full emotional lives for these “minor” characters.

How did your editorial background aid in your publishing journey?

Working as an editor that publishes mostly unsolicited, read blind work is incredible practice in developing taste. As the fiction editor of The Shanghai Literary Review (TSLR), I had complete freedom opposed to school with curricula, or established magazines with solicited writing and style parameters. TSLR was my first experience wholly owning the critical and editorial experience.

I learned about my own taste and sharpened it through reading submissions and seeing how much talent exists in the world. It was always breathtakingly humbling, exciting, and encouraging.

You’ve studied Russian and comparative literature, earned an MFA in fiction, and were a founding editor for The Shanghai Literary Review. How did these experiences shape your path as a writer?

I have been shaped by my experiences but at the time they felt inevitable. Of course, having certain teachers who introduced me to certain texts at the right time and place helped.

Could you share a bit about your experience breaking into the publishing industry and navigating the path to getting Shanghailanders published? What advice would you offer to aspiring writers looking to break into the industry today?

Shanghailanders is not the first book I wrote. My current agent is not my first agent. Sometimes things don’t work out; it’s disappointing and tough, but all you can do is start over from square one. Publishing books takes time and financial toughness, so take the time to pursue smaller wins. Whether that is publishing short form, contests, or nonfiction, keep your hope afloat. Keep challenging yourself to improve and learn. Finally: work a bit, travel a bit, and get yourself a job that allows you to save. All of these things help enable you to write.