An Interview with Jeff VanderMeer

Words By Jeff VanderMeer, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

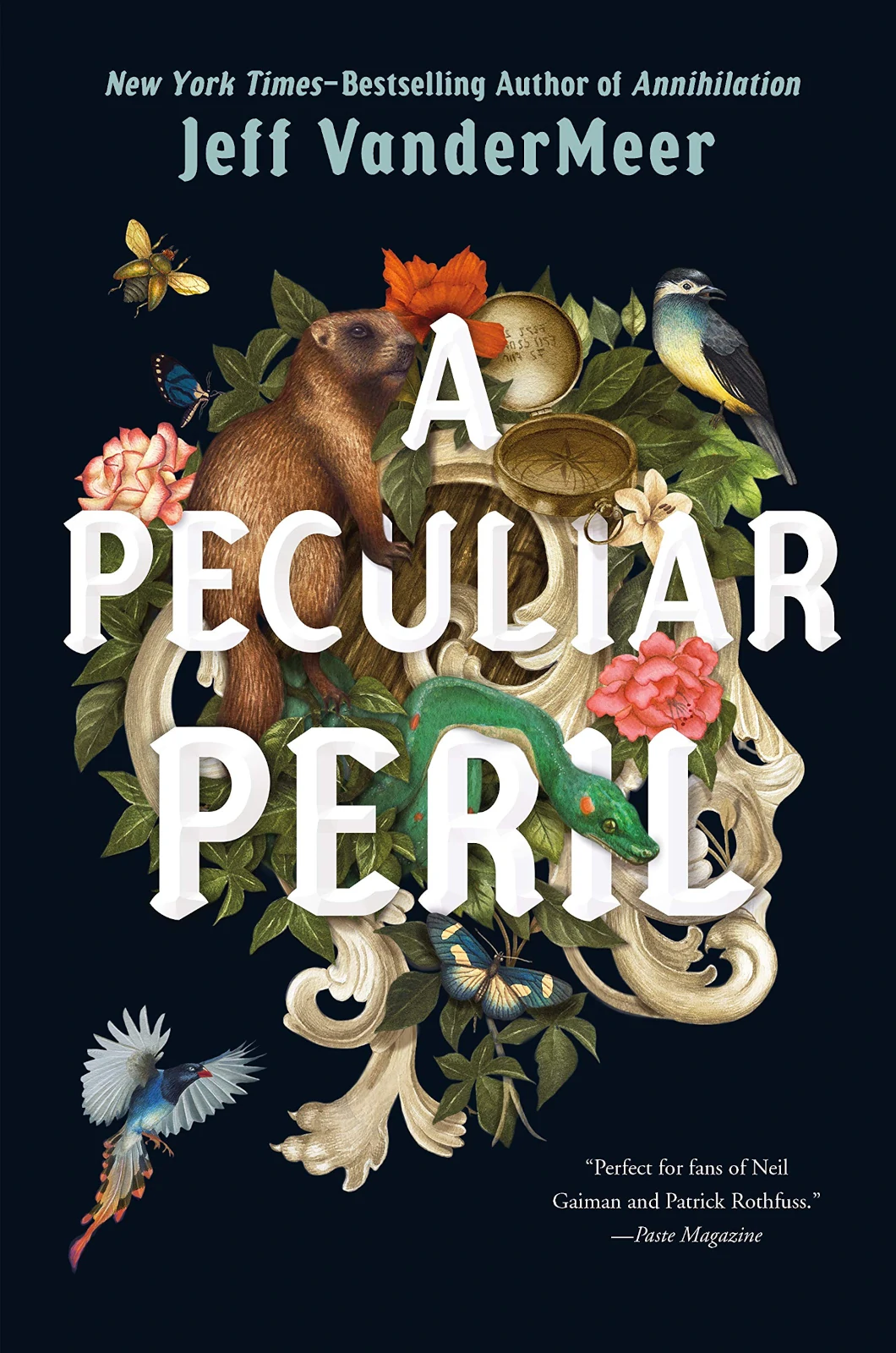

DH: I’ve been excited about A Peculiar Peril since you teased it in our interview years ago. What inspired you to write this book?

JV: Years ago, my wife Anne and I edited a fake medical guide called the Thackery T. Lambshead Pocket Guide To Eccentric & Discredited Diseases. It has all kinds of contributors, like Neil Gaiman, and all kinds of fake diseases that use the medical guide format to tell stories. We actually did readings where we were dressed in lab coats and people who weren’t there for the readings would do a double-take at ballistic organ syndrome or something like that. You can find it in a lot of medical libraries, sometimes appropriately stacked in the humor section, other times it’s with actual medical guides because of its strange format.

We did a follow-up with Cabinet of Curiosities about Dr. Lambshead’s cabinet of curiosities in his crumbling mansion. I wrote the introduction, which was basically the story of Lambshead’s life. Several years later I started wondering about what he’d been up to. I had this sudden flash of inspiration about his grandson getting embroiled in something to do with his mansion and his cabinet of curiosities. In A Peculiar Peril, his grandson Jonathan is bequeathed the mansion after Lambshead passes away and finds three strange doors that lead to various places, including an alt-earth called Aurora. Jonathan gets involved in this misadventure or mis-quest where it turns out Lambshead had been a part of an organization trying to protect and provide order on these doors between worlds. The one that’s closest to us, which is called Aurora, is a place where magic is real and a version of Aleister Crowley is the head of a Franco-Germanic empire. Crowley wants to conquer all of the different earths and he’s going to do this by capturing a celestial beast called the Golden Sphere. Jonathan has been tasked with trying to find it first. But things go horribly wrong; things are not quite what they seem. It really is a misadventure with a lot of humor.

You have a wonderful blend of epic world-building and underlying themes, but at the same time every other paragraph is laugh-out-loud funny. What was it like balancing an important narrative thread while maintaining that sort of Terry Pratchett humor?

There’s been kind of an underlying humor in a lot of my books. Even in Annihilation, I find the conversations the biologist has about whether this thing is a tower or tunnel could be kind of bleakly humorous. Even the bureaucracy in authority of the Southern Reach organizations, I think, is actually funny. The proportions in A Peculiar Peril are different in part because Crowley, this bombastic villain, is kind of based on reality. So you’re using this humor not to create a scene chewing villain but to get across, in part, what these people are really like. I think the wild magic of Aurora and the wild unpredictability of it brings about that sense of humor. Some of the stuff that I read growing up—comics, books, and stuff—there was this sense of the absurdity of things coexisting with the serious. And it just naturally developed that way. I was happy to, for once, showcase that side of what I can do, because most of the novels that I’ve written, with the exception of some of the stuff in City of Saints and Madmen, has required me to be very serious.

When we were talking about Borne years ago, that initial huge bear and kind of scientific-ish body came together for you in a dream and you pieced it back together. Did some of the more outlandish and beautiful, wild imagery come to you via dream inspiration, or were you just outside looking at chipmunks and thinking, what if those were flying and attacking people?

This is actually similar to what happened before I wrote the Southern Reach trilogy. For Southern Reach Anne and I put together this anthology called The Weird. That required reading about 6 million words of weird fiction in a fairly short amount of time. When I wrote these books, we were researching and reading for The Big Book of Classic Fantasy and The Big Book of Modern Fantasy and I think a lot of the tone and texture from classic fantasy rubbed off on me. When you do that, you get into this really interesting, absurd-logic place because a lot of folktales are absolutely batshit. I think the creators of those retellings took a lot of joy in how absurd they could get. There’s a story called “Hans, my Hedgehog” that we put in that book, which was a huge influence because of the hedgehog man who rides a rooster. Some of it came out that reading and some of it came from moving into this ravine area and I getting to know these animals in our yard. We have possums, racoons, armadillos, rabbits, snakes, owls, hawks, you know, almost everything you could imagine from north Florida. Because of the way the house is built, even just from the window, you get to know each animal individually. I think that rubbed off in terms of the individual personalities of some of the animals.

Crowley is, to some degree, your main antagonist, but there’s also John Dee and Napoleon, and of course we just have Napoleon’s head. What was it like to do a great deal of research and then adapt it to this alternate reality?

I tried to only use historical characters that I’d already researched. I already knew a lot about Kafka, who appears as an amphibious cop in the book. I had done a lot of research on John Dean for my prior novels.

As for Napoleon, I was once fascinated with how his military mind worked, and read this colossal, I think 2000-page, history book of his battles and political intrigues. I also read about Charlemagne and William the Conqueror who both appear in the book. William the Conqueror isn’t accurately portrayed in this novel, so I didn’t have to do a lot of research. I’ve also extensively studied and read maybe forty volumes of decadent era literature. I could get to the fun of writing them because I already knew who they were and didn’t have to do research. Then I mashed it all together because, in Aurora, certain things don’t quite happen at the same time. So there’s a Czech Republic that’s formed much earlier than here and there are certain characters who, in real life, wouldn’t have occupied the same time period. At the same time, there are characters like Napoleon who are just resurrected, conveniently. I like the idea of riffing off Napoleon, alt-Napoleon, and having him change over the course of the novel and providing a secondary character through-line for different events. You get some wider context from him at times.

Last time we talked about what your process has been like for your previous novels, where you tend to agonize for years and how you had some trepidation over the Southern Reach trilogy because they came so quickly to you. Where did this book fall in the range of Jeff VanderMeer writing styles?

The book formed over a fairly long period. I’ve been working on and off on it since 2010. The way I work is always in a bunch of scene fragments, so when I say “beginning work” on book two, I was already pretty far into it. I just hadn’t written the full rough draft. The idea for Dead Astronauts came to me and it was like this flash out of the blue and it was so poetically intense that I knew if I didn’t finish, I would ruin Lambshead by continuing it and I would also ruin Dead Astronauts by not doing it right away.

So there have been these little gaps, and all the gaps have been useful. I always feel there is a usefulness to having starts and stops and making you look at a narrative differently. I also feel like there has been a lot in my head about wanting to write about the world, wanting to write in some disguised way about Florida. I may have been processing and thinking about things a lot more in a general sense than I’d realized.

Talk to me about who you think your ideal reader is for this book, if you could conjure them out of a machine the way you do when making creatures.

I appreciate books that you can go back to at different times and see different things. There are certain stories, like the Dark is Rising books that you can read as a kid and come back as an adult and find new things to appreciate. There are timeless children’s classics that work the same way. And it’s not like an artificial thing where you think I’m going to build in an adult reaction to this novel rather than a teen reaction, it’s more, just going back to writing fantasy-fiction, which is what I started out writing. When I started out I wrote a lot of really bad pastiches, like Patricia McKillip novels, that were never finished or publishable. But that’s how I learned to write.

So in one sense, I felt like I was just going back to what I’d always done. The difference, of course, is that there’s a sixteen-year-old protagonist, despite there being a wide cast of viewpoints in the characters. At sixteen years old, Jonathan Lambshead, is a shy nature-loving boy and that, I guess, is the crux of thinking about the audience. But I’m also writing this character and following how I think they would react and what they would be like, so I didn’t really think about anything other than doing what felt right for this situation.

When it came time to sell it, there were offers from adult publishers and YA publishers. I think some of the adult publishers, though it was kind of them, wanted to make too many changes, like making Jonathan older. I just didn’t want to get caught up in that so that’s why it landed where it did.

I’m always a bit worried when adult writers write a YA book. I worry that it won’t be as dark as their other work. But in the first scene you put those fears to rest. What was it like writing for a different audience?

The way I look at it, I always do something different with every book. Even within the Southern Reach, all three novels are written in completely different ways. There’s always a central thing that has some preoccupation with the environment. Maybe this time it comes out with the animals and everything. But the books always come out very different. At the end of the day, it’s still a VanderMeer book. For example, I grew up in the Fiji islands, which is a British Commonwealth country. So, when I came back to the States as a nine-year-old I had a British accent, and had these bizarre experiences of failing spelling tests and such. With Jonathan, as he lives in both Florida and the UK, I kept coming back to those experiences.

So what’s it like now that everyone wants to turn everything you write into a film or a TV show? Has that changed the way that you write? Are you thinking about how things will look on the screen? Or are you still able to completely focus on the page?

As somebody who started with self-publishing and small presses, then got picked up by large commercial presses, I just do things to protect myself. It’s extremely surreal, at one point nobody wanted to publish any of this stuff and then people kept saying “these things are un-filmable.” So in one way, it’s very gratifying and in another way, it is deeply weird. For example, Hummingbird Salamander, the adult novel I just finished—which is about bioterrorism, ecoterrorism, wildlife trafficking, and the end of the world—is one of the few books of mine where the challenges are different because there’s one central mystery to be solved.

But this is a different challenge because there is something that has to be solved, which is the direct through-line that everything falls off of. It’s a different kind of complexity, a different kind of structure, one I felt very comfortable selling it to Netflix—based on one page of summary—because I knew the kind of novel it was. I already new who the character was. I couldn’t really get screwed up by the fact that somebody had optioned it.

There are certainly novels I would not have been able to do that with. Getting my editor’s notes, it’s pretty clear I was correct about this. I had the through-line, the bones of it and the structure already down in my head. My editor had no structural edits. The only edits I received were about lack of clarity. It’s entirely possible that selling a story before finishing a manuscript could have screwed me up. The novel I’m working on next, Drone Love, I definitely would not want to pre-sell until I have a draft finished. The short answer is, I think about it and I either channel it or I just find ways to protect myself.

Talk to me about what we can see next from you, as I’m sure everyone will devour this 700-page book in a weekend and want more.

Well, coming July 20th is The Big Book of Modern Fantasy, which is the companion volume to The Big Book of Classic Fantasy. Together, they’re 1 million words of fiction covering the early 1800s through the early part of this century. It’s the most comprehensive two-part anthology, so to speak, of fantasy. It has more translations and is more inclusive than any anthology. I keep saying to people, that was actually a fairly low bar in the English language. It’s possible another anthology could eclipse it in ten years, which I hope happens.

At the end of the year, the trade paperback of Dead Astronauts and also the hardcover-omnibus reissue of my three Ambergris novels will be out. Then next year, in April, Hummingbird Salamander will come out. I also have a short story collection tentatively titled Nice is Just Another World for Terrible that will come out at some point. In 2022, two Jonathan Lambshead books will also come out, which conclude that series.