An Interview with Jade Song

Words By Jade Song, interviewed by Sara Santistevan

In an interview with Write or Die, you mentioned that you consider yourself an artist over a writer. How do you think the role of an artist differs from the role of a writer?

To me, there’s really no difference between being an artist and being a writer. My writing is part of my art. Writing is just one part of the art I make and love, so therefore I think of myself as an artist. My favorite art of any kind understands and celebrates the lineage and inspirations it comes from, so whatever I craft, whether it be writing or not, I always seek this approach.

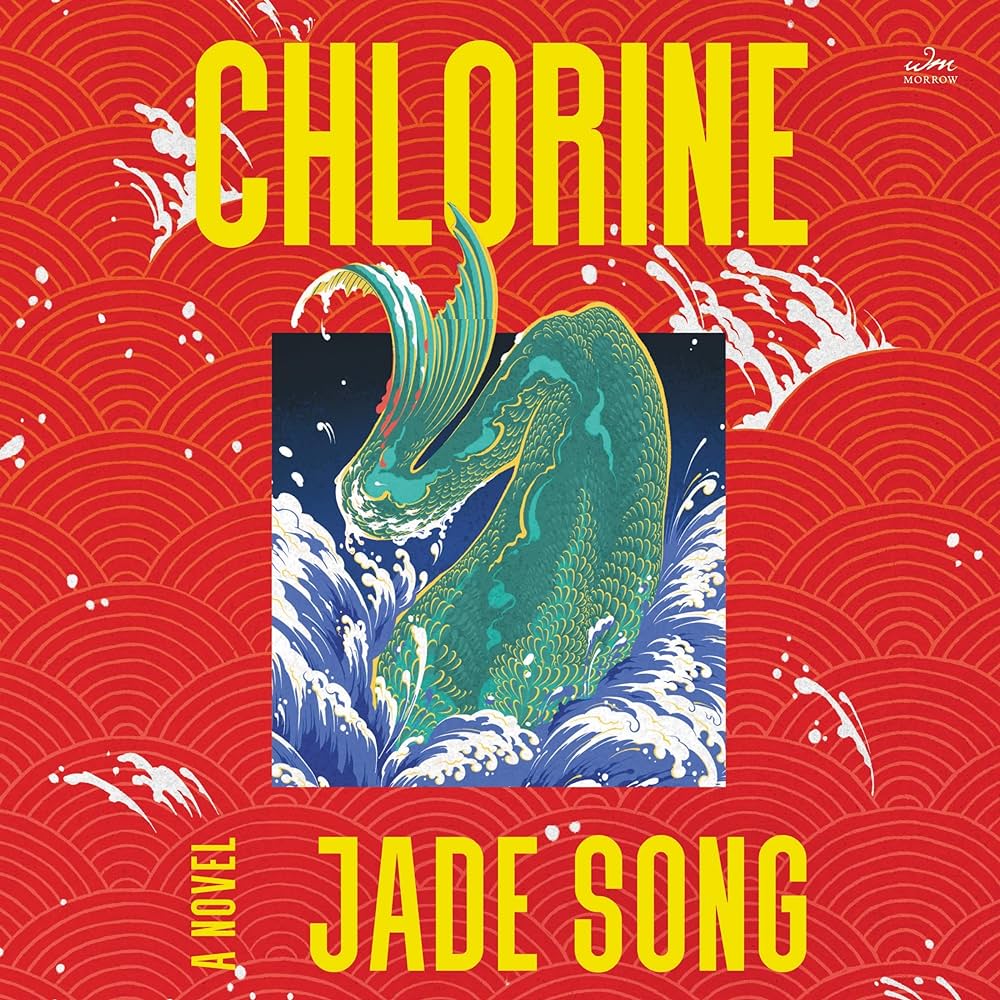

Ren’s coming of age in your debut novel Chlorine is so heartbreaking and raw, yet oddly comforting. There aren’t many stories that describe the violence of coming of age as a queer girl of color in the US this honestly. How important was it for you to center Ren’s identity as a cultural “other” in your exploration of the pain of girlhood?

I don’t view Ren, or queer girls of color in general, as a cultural “other”—if anything, I view her, and me, and us, as the center, which includes all the complexities of who she is and who we are. If anyone wants to view her as an “other,” that’s their own conundrum to work through. I wrote this exploration centering her and her experience.

You’ve mentioned that you’re fascinated with imagery of “weird, queer transcendence,” and that this played a role in writing Chlorine. How would you compare Ren’s transcendence to Cathy’s lingering longing for Ren evident in her letters? Do you think Cathy is unable to transcend, either similarly or unlike Ren?

To me, Cathy transcends in her own way: she’s in love with someone else. To be in love is to be terrified; to be in love is to choose the terror despite; to be in love is therefore to transcend. Yet being in love with another is a common form of transcendence in the way Ren’s viscerally weird and strange transcendence is not. So, comparatively, Cathy’s arc pales.

There are at least two distinct forms of cell death: pain-free programmed cell death (apoptosis) and inflammatory unplanned cell death (necrosis). Menstruation is necrosis meaning anyone who has a uterus literally goes through a process of death and rebirth every month. Unfortunately, Ren still struggles with painful periods, even at her most dedicated to competitive swimming. Can you tell us a little more about how you sought to link the violence of menstruation with Ren’s bloody transformation?

Thank you for that interesting fact. Cell Death would be a great band name! I think there was no way for me to write a coming-of-age girlhood-driven story involving body horror without including menstruation. To me, it’s biologically violent, gushing out blood and stomach pain like it’s no big deal, and, as you said, it’s a monthly bloody transformation, so when writing fictional bloody transformations, I just can’t leave it out.

You’re also a fantastic short story author. In “Bloody Angle,” the narrator explains their vengeful cannibalism by citing Newton’s third law: “For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.” Racism plays a crucial role in “Bloody Angle” and Chlorine. When expressing your characters’ anger towards prejudice, did you ever feel pressured to justify their actions to people who wouldn’t understand?

Thank you! I never really feel pressured to justify characters’ actions to people who wouldn’t understand because I’m never really thinking about people who refuse to understand. When I write, I’m thinking about me and my friends and my community and my family and everyone/everything else I care about.

Yes, there was some need to justify the reactive acts of violence—the murders in “Bloody Angle” and the body horror in Chlorine—but the justification is more so to explain the character motivations and plot. After all, the narrator in Bloody Angle says, “If you are struggling to understand… my story is not for you.”

You’ve expressed how Chlorine came from a place of cathartic anger, while your short story collection and novel in-progress come from a place of love and understanding. How did you allow yourself space to safely express your anger without letting it consume you?

Art has always been the safest channel for my emotions. The making, the gazing, the understanding—it’s incredibly life-affirming and lifesaving. It’s because of art that my meanest inclinations and worst rages do not consume me, so just by allowing myself to listen to the art I then become free.

You have a beautifully curated Instagram account, @chlorinenovel, to share updates and related artistic influences you enjoy. What forthcoming books, movies, music, or other forms of media you are looking forward to consuming?

I can’t wait for the new Jackie Wang book, Alien Daughters Walk Into the Sun, to arrive in the mail. In 2024, I’m excited to read the new Akwaeke Emezi novel, Little Rot, and the new Hanif Abdurraqib book. I’ll be seated at every new Hansol Jung play in theatres, and I’ll be the first in line at the cinema when Julia Ducournau’s next film with A24 is out.

If you could give your past self one piece of advice about the publishing industry or process, what would it be?

You can say no.

Do you have any advice for aspiring authors?

Writing and being a writer are two different things. One is to focus on the work, and one is to focus on the community, the success, the end product. Neither are wrong, and both feed into each other, but I do think deciding which path is more important to you will make everything else come easier.