An Interview with J.T. Greathouse

Words By Haley Lawson

The Hand of the Sun King is a coming of age story of a boy struggling between two paths: that of his father’s lineage to follow the empire’s structure and hierarchy and that of his grandmother’s rebellion and magic. Where did the concept for The Hand of the Sun King come from?

The book itself—and the whole trilogy, really—grew from the original idea for Alder / Foolish Cur as a character, which was inspired by my senior seminar in history class as an undergraduate student. We were reading the book Orientalism by Edward Said, a formative post-colonial text written by an author who was, himself, a member of a colonized community who was educated by the power that had colonized his people. I found that dynamic—being a person with every reason to hate an empire, who then came to work within it, then came to critique it—very fascinating, and Alder / Foolish Cur’s character arc sprang from that fascination. His parentage and the conflicting paths it offers him were a way to put that element of his character on the page from paragraph one and add some emotional layering. Other elements of his character, such as his dual name, originated from other inspirations, in that case from Ged / Sparrowhawk’s naming in A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin, which was one of the books that made me want to be a writer.

More broadly, the Pact & Pattern trilogy tries to explore the ideas of structure and hierarchy in a general sense. Particularly the third book, The Pattern of the World (releasing August of 2023!) is interested in how structures can both empower us and limit us. But no structure represents a complete and accurate picture of the thing it is meant to categorize—there is always, inherently, some element of simplification. Alfred Korzybski, the Polish-American scholar of semantics coined the term “the map is not the territory” to capture this idea. A map allows you to navigate the world, but to do so it must simplify the territory it represents. Roads become lines, hills become topographic abstractions, and so on, rendering the territory into a manageable, quickly comprehensible, and useful representation. If the map were a perfect representation of the territory, it would be useless as a map. Similarly, structures in society, in culture, in politics, in science (and in magic!) allow us to do useful things by simplifying the wholeness of reality. The pact shrinks and simplifies the pattern. But there is always the risk that something important will be lost and overlooked along the way. These novels are trying, at least, to explore that idea.

There is a continuous tug and pull with Wen Alder between siding with the Emperor versus siding with Alder’s mother’s heritage and rebellion. What propelled you to have this kind of conflict and did the early drafts include this dynamic as well?

That element was always present in the early drafts. In fact, it was present in the original novelette, which largely maps onto the An-Zabat section of The Hand of the Sun King, which I wrote before deciding to turn Alder’s story into a novel and then a trilogy. Again this reflects some of the original inspirations from post-colonial theory. For the elite, educated class within a colonized group there is often a continuous conflict—both personal, and between members of that class—between resistance to the colonizers and complicity with the colonizers for the sake of personal advancement (and, for some, the perceived possibility of helping their people integrate into the colonizing society). Alder has very little national, class, cultural, or otherwise political consciousness until the midpoint of the book when he begins to realize that the Empire, though it might provide him with the things he wants and needs—or at least some watered-down version of those things—is in fact doing tremendous harm in which he is complicit.

I think the best fiction centers on characters who have to make a genuinely difficult decision. I wanted to write a book about structures and hierarchies, about Empires and why people might choose to do horrible things in service to them. Alder thinks working for the Empire will help him become the kind of person he wants to be and learn the things he wants to learn, but in truth it can’t do those things. It can only turn him into a useful tool. But it’s hard for him to realize that, to accept it, and to risk not only his life but his vision for his future. I think that’s fairly universal. How many of us operate within systems, or lend our labor and time to institutions that, if we were to take a moment to reflect, in fact do tremendous harm that we would not want to take responsibility for? For example, I work for the public school system in the United States, which I know is a deeply imperfect institution despite the best intentions and efforts of the people involved in it. Reckoning with that is hard, but necessary if we want to improve things.

I really enjoyed the aspects of world building you included that exposed cultural differences within the Sienese Empire. I’m especially thinking of when Wen Alder had to learn a different language and he compares the differences between character and letter languages. How do you approach world building on such an epic scale?

I think my bachelor’s degree in history has helped quite a bit. If you look long enough at any society, in any period in history, you start to see that it’s really an amalgamation of cultures and societies. We tend to talk about historical groups as though they were very homogenous—the Victorians did this, or the Roman Empire did that—but really what we’re describing is a rough estimate of the average based on the writings and artifacts we have access to, which were usually left behind only by small, elite groups within those societies. It comes back to that whole “the map is not the territory” idea. There’s an inherent necessity to simplify the complexity of the real world when writing fiction—particularly when doing so in a secondary world, where you have to invent elements or carefully and intentionally draw inspiration from real-world cultures—but I think it does a disservice to our stories when we fall into the trap of letting our worldbuilding become too simple.

It’s actually a frustration of mine in a lot of fantasy fiction. You have these massive continents with, like, two or three languages, or cities that have these super coherent and homogenous cultures. No real continent or city is like that, or has ever been like that. It not only ruins verisimilitude for me, it also does a disservice to the reader—because whether we like it or not, readers derive some of their understanding of how the real world is from how fictional worlds are portrayed. If people don’t look at the real territory, all they have to go by is the map, so we have an enormous responsibility as writers to try and make our maps as accurate as possible. The real world is vast and diverse, and our fictional worlds should be too. That means investing the time and attention needed to fill them with as much complexity as we can. Which, ultimately, makes for more interesting and entertaining books anyway.

The real world is vast and diverse, and our fictional world should be too.

Did your past work experience as an ESL teacher in Taipei influence your writing or understanding of the craft at all?

I don’t know that it did, beyond maybe a little more attention to certain grammatical rules in English that aren’t explicitly obvious to native speakers until you think about them (for example did you know that “fewer” is always used for a set of distinct objects you can count, while “less” is used for less tangible, uncountable things? A pie might have fewer apples, and therefore taste less sweet. It’s actually incorrect to say “less apples,” and you certainly wouldn’t say “fewer sweet”). Teaching your own language to people who didn’t grow up speaking it forces you to think about and codify lots of things that you do by instinct, but that actually do have consistent rules.

My time living in Taipei definitely helped shape me as a writer, in that I was fortunate enough to find a really excellent writing group (mostly of other ESL teachers, or former ESL teachers) at a moment in time when I was just starting to get good at writing but needed a support and feedback system to maximize on that momentum. Some of my first published shorts were initially critiqued in that group. But also, I think living as a foreigner, particularly when you’re living in a culture that’s substantially different from your own, helps shift your perspective on things. You’re forced to look at the world a little more closely—or at least you have a good opportunity to. I definitely brought some of that heightened level of attention back with me when we returned to the United States, and it’s made me think about things (and therefore write about them) in ways I didn’t before.

You’ve noted before that you’ve been writing since you were 11 years old. How has your writing changed over the years? What experience did you gain that you would recommend for writers seeking publication?

A lot, I should hope! I don’t go back and read things I wrote as a tween and teen because I’m afraid my cringing would cause me to collapse into a black hole and destroy the planet, but I do occasionally revisit some of my earlier published short stories, and I definitely see things in them that I would do differently now. Which is good! The goal of a writer (and any craftsperson or artist) should be to get better with every project—every page, every paragraph if you can manage it. You do that through reflecting on the work you like, then reflecting on your own work, and seeing the gaps. Whenever I read something I really love I stop and ask myself, “What is this doing that I’m not doing? How can I take something from what I loved about this and use it to make my work better?”

As far as advice for writers seeking publication, I don’t really have much. I think the industry moves so fast that any specific strategies I had when I was first selling short stories in 2016, or looking for an agent in 2018, are swiftly becoming irrelevant. What I did do, that I think anyone trying to get started in any industry should do, is try to learn as much about the industry as I could and try to connect with other people at a similar point in my then-nascent writing career. Look for communities of other people with similar goals to you and connect with them, exchange feedback, share information. Don’t just network, make friends. Be helpful when you can, and ask for help when you need it. A rising tide only lifts all boats by way of solidarity.

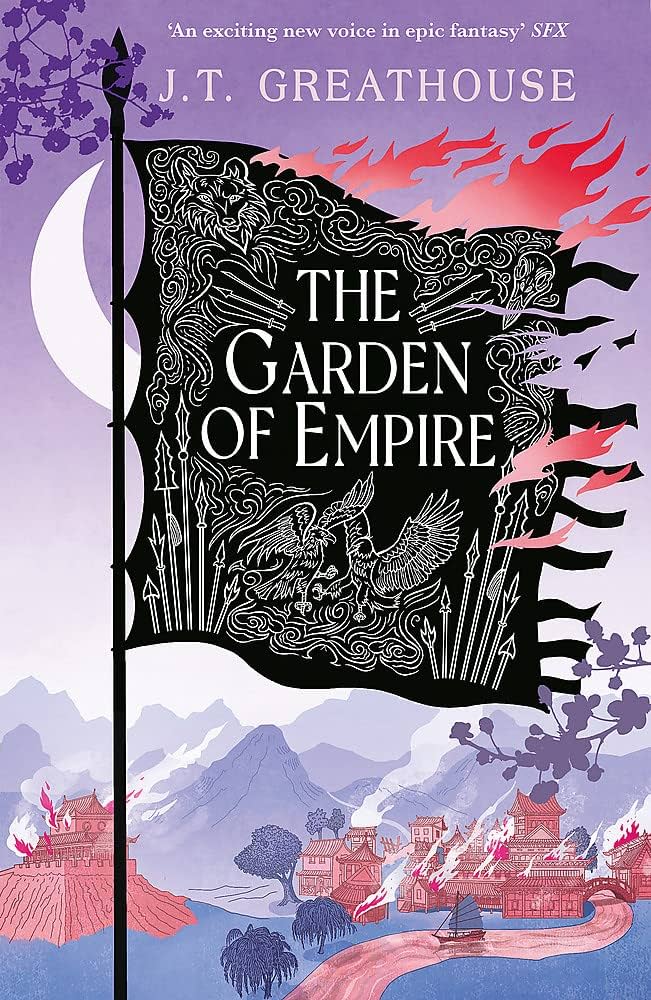

The Garden of Empire is the second in the series (Pact & Pattern). What was it like to draft a story that spans several novels?

Difficult, in a word. Growing up I had written a lot of standalone novels that will never see publication, but Pact & Pattern was my first attempt at a trilogy. Trying to make each book in the series function not only as a story for its own sake but as part of a larger whole was very challenging for me, partly because I had all these other non-Pact & Pattern ideas for stories that I didn’t have time to work on yet while I devoted four years to the trilogy. I would often find myself having to work on Pact & Pattern while my creative brain wanted to think about some other idea entirely. In fact, the frustrations I experienced have motivated me to try a different approach with my next project—something more similar to Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels, books with a shared world and themes but distinct characters and plots, to give me a bit more freedom to chase fun, new ideas with each book.

I’m mostly a discovery writer, meaning that I don’t write from a rigid outline but sort of work my way through the story from beginning to end. That said, from the time I decided to turn the original novelette into a novel I knew what the ending of the whole story would be. It just wound up being a story that needed more than one book. A lot changed, though, from the first draft of The Hand of the Sun King to the final Pact & Pattern trilogy. At one point, the first book had a framing device from the perspective of a character who doesn’t even appear until The Garden of Empire now, and who is now not a point-of-view character at all. That process of figuring out how to tell the story was hard, and required a lot of isolating ideas and deciding what the purpose of that idea was to the overall story being told, and then deciding whether or not the idea was worth that purpose. A long process of refinement that, frankly, was more tedious than exciting at times.

The third book, though, The Pattern of the World, was a delightful breeze to write. By that point, I’d figured out what I was doing.

What are you most excited for readers to get out of The Garden of Empire?

The Garden of Empire really expands the world of The Hand of the Sun King. You get to see corners of the Empire that were only hinted at in the first book, and you get to see some perspectives on events other than Alder’s own, which I think adds interesting layers to the plot, characters, and themes. You also get to spend more time with some of my favorite characters from The Hand of the Sun King who only had minor roles, or didn’t show up until the very end of the book. The Garden of Empire is also where the bigger ideas of the series—the real, deep, philosophical things underpinning the post-colonial ideas of the first book—start to emerge, which really come into their own in The Pattern of the World.

What other book(s) do you want people to be aware of this coming year and why?

To plug myself first of all, the Pact & Pattern trilogy will come to a close with The Pattern of the World in August this year. If folks liked The Hand of the Sun King, there’s time to read through The Garden of Empire before the third book releases—maybe even time to preorder!

Otherwise, I really loved The Tyranny of Faith by Richard Swan, which was released earlier this year. His Empire of the Wolf series, which started last year with The Justice of Kings, does a great job of the kind of complex worldbuilding I love to see, and has some excellent character work. I’d also encourage people to pick up Flames of Mira by Clay Harmon, which releases in paperback in July, and keep an eye out for the paperback release of The Spear Cuts Through Water, which was my absolute favorite book last year.

I just started reading an advanced copy of a book from TorDotCom called The West Passage by Jared Pechaček, which will be released in 2024. So far, it’s weird and fascinating, and I’m pretty into it, so keep that one on your radar too!