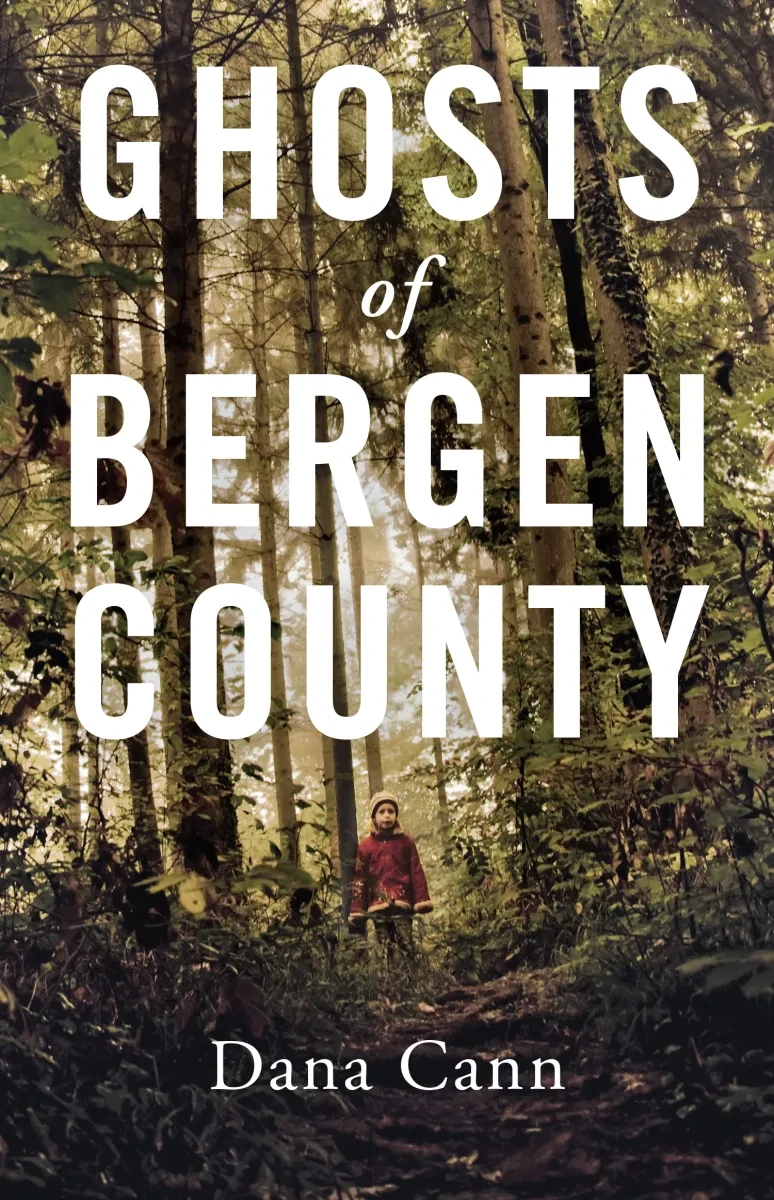

An Interview with Dana Cann on Ghosts of Bergen County

Words By Dana Cann, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

Although Ghosts of Bergen County is your first published book, it’s the second book you’ve written. Can you talk a little bit about how these two books differ and what you learned from writing the first?

My first novel was called The Happy World. It was never published. It’s the novel I needed to write in order to learn how to write a novel. I hear this is pretty common—that many writers write a novel or maybe two before they’re able to write the one that will be published. I probably spent four years writing The Happy World, and another year or so in a futile agent search. But these weren’t wasted years. I learned a lot writing that first novel, and by the end I was able to recognize its fatal flaws—that it was too bleak and the structure was too ambitious. I was working backward in the novel. There’s a reason why most stories start at the beginning and end at the end. I was determined writing Ghosts of Bergen County that the story had a discernible forward momentum. I tempered the bleakness, too, with hope and a way out of the metaphorical woods the characters begin the novel in.

Where did the idea for the book come from?

I woke one morning having had a dream in which a friend and I, in the dream, took heroin and shoplifted in a mall and were chased by store security. I have lots of dreams but this one was so vivid and inexplicable. It seemed important. I’d also been thinking about writing about a hit-and-run accident. Those were the two thin threads that launched the novel and I went from there. The scene in the mall based on my dream occurs about a quarter of the way through the novel.

Although each of your characters are very different, they are all united by severe pain and loss in their lives. How did you manage to create a lively and forward-moving story when the characters at the helm of the plot are struggling with so much unhappiness?

The novel takes place over a single summer in 2007. It’s really a novel about overcoming grief. The tragedies the characters have experienced each occurred some number of years ago. Yes, the characters are struggling with unhappiness, but the novel is about discovering a way out.

When you were writing this story, did you always have an ending in mind?

Absolutely not. I write to discover the story. I’m not the kind of writer who works with an outline.

When I started writing this novel I knew that my characters would be using heroin and that there would be the shoplifting scene I mentioned earlier. According to my computer’s hard drive, the first file I saved was called “Ghosts,” so, apparently, I knew that would be an element, but, to be honest, I don’t remember whether those ghosts were to be literal or metaphorical. In the book that I wrote they’re both.

After a few false starts, I discovered my characters and then the story.

A huge element in this story is drug use, from the recreational use of heroin to the medical use of antidepressants. How important is this element to the narrative? Do you think it would be the same book without it?

I think the drugs are very important to the book. My characters are grieving, and, to a certain extent, have become locked in a cycle of grief that they can’t escape. The drugs are a way to escape grief. But, for my characters, the drugs themselves become another symptom. At one point, Gil, my protagonist, reflecting on his heroin use, wonders whether he’s cheated grief. That’s a major theme in the novel.

Talk to me about the publication process. How did you hunt down your agent?

Getting an agent was not easy. As I mentioned, I’d written a novel before and had gone through a year-long search and came up empty. I’m not the most outgoing person, and I don’t go to a lot of conferences. I know some writers who are able to get agents that way, or, better yet, their friends are writers and can recommend their agents to them. I did a little bit of that, but most of what I did was go through Internet databases that agents have joined for the purpose of hearing from unagented author. I also read the acknowledgments page on novels I liked that I felt were similar to mine to see who these authors were working with, and then sent my pitch to that agent, mentioning the book I read that’s similar to mine, etc. I did all these things in 2012, after I thought I’d completed Ghosts of Bergen County. After a little more than a year, after I’d gotten one final no from a wonderful agent who expressed dissatisfaction with the ending, I pulled the book back, reworked the ending, and started sending it out again. I was actually getting less traction the second time I went through it and it was becoming disheartening, because I thought the new ending really worked, but I did send it to a new agent—a guy out of Austin, TX with no connection to New York—and he loved the book, got it right away, and he wound up taking it on so it all worked out. But the only reason I got his name was off of one of those databases.

So when you started writing this book—when you woke up with this dream and decided to put it to paper—how much time passed before you got to see it in print?

Eight years. Probably four years for the first draft and, like I said, it was well over a year before I really got moving on it. And then another year of revisions—maybe four or five months before it was accepted, then a year getting it into print after it was accepted. One thing I will say is that I can’t underestimate the number of revisions the novel went through. Even after it was accepted, my editor at Tin House pushed me very hard, in a good way. I probably did two or three rewrites after it was under contract. But it’s a much better novel for all that work.

It feels very tight. You’re clearly tapping into an economy of language—none of it is superfluous, and I suppose that’s what eight years of revisions will do: create an incredibly tight book. So overall, how have you enjoyed working with Tin House?

Tin House has been great. I have always submitted my short stories to Tin House. I go through this process when I believe a story is complete—I’ll start sending it out and Tin House is always at the top of that list. Great magazine, great reputation. They never gave me one word of encouragement on my short stories at the magazine. I’ve never had anything accepted there, so I was just ecstatic and surprised and beyond pleased that they wanted this novel. But like I said—my editor there, Meg Storey, has been great. She’s really pushed me in ways that didn’t always feel comfortable, but the novel is so much better for it.

That’s really wonderful. Tin House is always at the top of my submission list, too. I’ve always loved how much emphasis they put on visual aesthetic, as well as excellent literature. How has the advanced release of the book been?

It’s been good. It’s my first time through this process, so I don’t necessarily know how it’s supposed to go. It’s a little slow…we’ve been waiting on getting the trade reviews—Publishers Weekly finally came out and that was a positive review. I got a very positive review from Library Journal too. Right now it’s a lot of waiting around, doing things like this—interviews. My publicist at Tin House is working hard to get the book reviewed. A local newspaper is going to review it, and Tin House is setting up some readings, so things are happening. And the reception to the book has been very positive.

The last thing I always like to ask is: what’s next for you?

I’m always working on new stuff and I have a couple good ideas for novels. I’ve taken a pretty good shot at one of them, though I’m not far enough along to realize whether or not I have enough to get me to the end. But I’ve started a science fiction-type piece about a NASA scientist who has this awful rash, and he’s convinced that aliens are orbiting the earth. They’ve found us out because of the electronic signals that we are emitting into space. Where that’s going to go—I have no idea. I started writing it last fall but have kind of taken a break from it because of revisions for the book. I want to write a mix of short stories and definitely a new novel at some point—but there is a lot going into this book launch right now and that’s a little distracting.