An Interview with Dana Brown

Words By Dana Brown, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

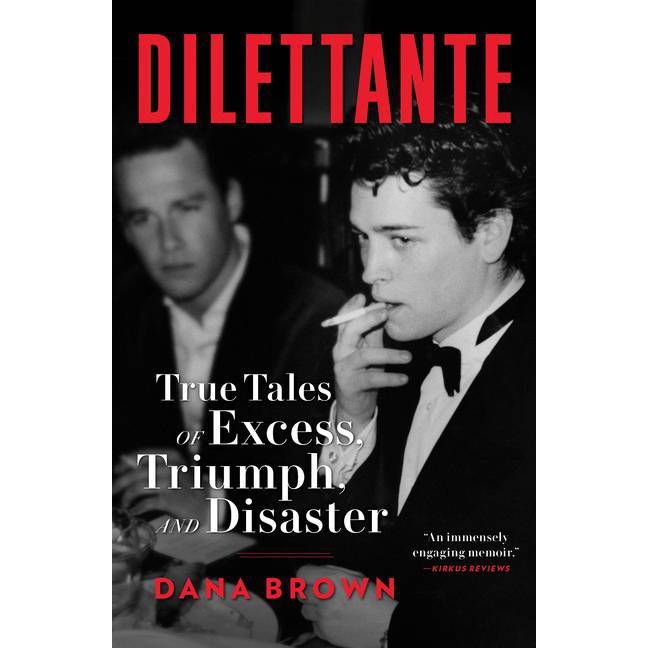

In the prologue, you wrote about how you had been working on Dilettante: True Tales of Excess, Triumph and Disaster for years, so when did this become a book?

About 10 years ago, I had written a TV pilot and sold it to Hulu. It was a comedy set in the dying world of magazines in New York. The main character was a version of myself in what was by then already a crumbling industry. As always happens in television, it didn’t go anywhere. And a number of people said, “Why don’t you write it as a memoir? And tell the story of the good old days as opposed to the downfall.” But I always thought, “Oh I’m not the one to tell that story.” But a year after I was pushed out of Vanity Fair, back in February of 2018 after Graydon Carter retired, something shifted and I asked myself, “Why not me? I do have an interesting story and tales to tell.” It then all sort of came together after that. I spoke to a number of former colleagues after the book came out they were all like, “Oh, you are the only person who could have told the story of this magazine in that era.” It was a huge weight off my shoulders.

I’m so fascinated by how every aspect of the story seems to be battling gargantuan levels of imposter syndrome. How did you overcome that? Has it become easier from when you were 21?

The short answer is no, it hasn’t. At Vanity Fair, I had a deeper learning curve than anyone else because I didn’t go to college and was wholly unprepared for this job. I had to really gain that experience while working, so it’s hard for me to look back and pat myself on the back in any way for anything that I did. And the book is colored by that feeling, but at the same time, this sense of “not being good enough” is universal. I think even the kids who came to Vanity Fair with graduate degrees in journalism were also feeling the same thing.

It was interesting how the New York you described in this book is certainly rough and broken in interesting ways, but it’s also full of an extraordinary amount of kindness. How did you find parts of New York that maintained this Midwestern feeling of goodness and stepped away from a cynical lens?

When I began writing Dilettante I was feeling really disillusioned with New York, which was definitely a central character in the book. This stemmed from its shift, which I wrote about, from being a creative mecca to a financial mecca. I think those of us in creative fields, especially from generation, had a bitterness about being pushed aside. It was no longer our party. But in the course of writing, I came to a number of conclusions, one of them being that everything changes—people change, cities change, across generations and decades. That’s just the arc of history and you can’t stop it. Secondly, I realized how I changed from when I was in my 20s. Of course the city seemed more fun in the good old days because they were my good old days and I didn’t have the pressures of being a grown up. I was in my 20s. Everything was better in your 20s. Finally, because I wrote much of this book during the pandemic, when I was watching the city suffer, I found myself wanting to celebrate it and I began to appreciate the city again in ways I hadn’t in a really long time.

Right before I started your book, I was reading a light-level erotica, and interestingly, the description of 41st Lobby and that of a naked woman laying on a bed was very similar. It shows how you painted the scenes with so much care. Was that something that came innately to you? How did you intimately take us back right to that very moment?

Memory is a funny thing, and something happens when you start writing about the past, especially when it’s your own story, and through a snowball effect, all the little details get unlocked. I was amazed by how everything came back to me, because I didn’t have a diary or notes from anything, I just had these little pieces of information that would pop in my head, sometimes in the middle of the night, and I would get up and sit there and write four paragraphs in incredible detail of this silly little thing that all becomes part of this bigger tapestry in the memoir. I also had 25 years of back issues of Vanity Fair which triggered so many memories, like how I was a photographer briefly for a year, and got so drunk with Christopher Hitchens that I could barely focus the camera to take his photo, on this day trip to Washington, D.C., and I was like, “Oh My God, this is how I get that larger than life character in the book because I had this wonderful experience with him.”

So, aside from your midnight recollections and a literal catalogue of what you did for decades, did you take friends out to lunch and ask them questions? Or was it mostly just you and your own mind when digging all of this up?

I did set out to do interviews of writers, editors and friends but then the pandemic hit, and I instead talked with a smaller pool of people and asked questions like, “What was the lunch place we used to go to in the 90s? What was the name of the guy who worked in the library?” So I did have a network but there were no official sit-down interviews with people and I don’t regret it because I think that might’ve muddled things a little bit between my memory of events and that of others. Like Robert Evans said, “There’s your story, there’s my story, and then there’s the truth.” And there’s something to that because we all remember things differently and we had different experiences in different moments.

Speaking of voice, how did you develop yours? How did you balance elegance and making it so personable?

First of all, I worked with extraordinary writers so I absorbed a lot from them over the years. Two writers that I worked with very closely and were also my dear friends were A. A. Gill, the brilliant English critic and travel writer whose descriptions and use of metaphors were just unparalleled; and Rich Cohen, who is one of the most gifted natural storytellers. When you have a conversation with Rich, and then you read him on the page, there’s literally no difference, it feels like he’s speaking to you. Rich’s conversational style and Adrian’s use of metaphors and his descriptions were two things from two of my favorite writers—and two of my dear friends—that I just ripped off. Another great cliche quote is, “Good artists borrow, great artists steal.” I’m willing to admit that I was massively influenced by those two writers.

So, you’ve described this book as a coming-of-age story. Was that always the goal or did it just come together through writing?

I didn’t set out to write a coming-of-age story. When I spoke to Ballantine Books, I kept telling them, “I don’t want to be part of the story. I want to be a fly on the wall, where I happen to be in these places, but I had no effect on them and they have no effect on me.” I really did not set out to write about myself, but the more I brought myself into the story, it made everything a little richer and it is often the case and makes everything pop more. And I really owe it to my editor, Pamela Cannon, who pushed me into putting more of myself in the book which really opened me up as a writer, gave me more freedom and brought a lot to the story. And I did tell her after that it was totally the right call.

Along with a coming-of-age story, we were also witnessing a coming-of-death story of the print industry. What do you think will be the long term effects of that on our entire culture?

Oh, boy, that’s a big question. When I look at the march of technology, it has happened throughout time and there’s always been an undercurrent of disruption, which never occurs overnight. From the barely functioning internet in the 90s to the launch of Amazon to luxury globalization to a tonal shift in media with the introduction of Gawker and TMZ and finally, with the coming of iPhones in the market and the boom of social media, all of these happenings have pointed out the cyclical nature of changes in economies and technologies. In the media, especially, the internet was seen as this democratizing tool that gave power to the people and took power away from corporations. But from a slavish devotion to truth and fact-checking, it’s all become about speed and eyeballs now, resulting in the spread of disinformation by those who claim to be news sources, mostly with anonymity. And these false facts are then used to insult and threaten people. All of this is alarming and shows how we’ve lost our morality and those human connections that make us decent.

This is not to say that technology hasn’t resulted in great innovations, and I hate coming across as the old man looking down on things. Maybe we haven’t hit that inflection point where everyone realizes what a disaster this is, and we need to clean everything up to sort of save humanity and culture and the future. But I don’t have much faith in mankind.

Your entire memoir is a love letter to narrative as much as it is to New York. How do you see the fall of print affecting your own narrative? Do you feel differently about who you are now that the institutions have crumbled?

Identity is such an important word right now on so many different levels, but when so much of it is established online, that’s not who you are as a person at all. It is a phony, curated version of you. And that really scares me, because we didn’t have that when I was growing up; you had to leave and go somewhere else to reinvent yourself, but technology has made that so much harder.

Today, I’m incredibly comfortable with who I am and what I’ve accomplished, but this didn’t happen overnight. Once I was out of Vanity Fair, a place I started working at when I was 21 until I was 45, it was a difficult transition for me. I realized that I wasn’t in demand and the tech companies weren’t looking for someone like me. With my identity super tied to Vanity Fair, where I spent a big chunk of my life with one group of people doing one thing, I found myself having a full-blown identity crisis where I began to question my narrative and wondering if I was just playing a role for 24 years. And it really took me a while, with some serious therapy, and writing this book was also a part of that therapy that helped me come to terms with my identity. I was learning as I went along, I was changing, and I was becoming who I am today, and that’s all we have. Our whole life is our whole identity which is tied into our past, but once you’re here, in the present moment, you need to learn to live and accept yourself. If you were disappointed in things you had done or had regrets, then just change course, anyone can do it. Own your life’s work and accept who you are.

You talked about how your editor pushed you to be much more personal in the book. Has that led to a point now where you bring more of your personal life into your writing?

I think the secret is that with every writer, whether you’re writing a film, or a novel or even nonfiction, there’s this terrifying moment when you realize, ‘oh, fuck, I’m a writer.’ I never thought I was a writer, so I never really made that much effort in writing until this book, which made me understand that this is how I express myself and tell people things about me. I recently wrote a movie and I found much better results when it was half about me, and it strengthened the realization that I’m a writer, this is my fate, this is how I express myself. When you look at great art, you wonder, “How did they come up with that? How is it that they’re the only ones who’ve ever been able to do that?” But that’s really how it is: artists express the shit that’s rattling around inside their brain on a canvas with different colors and brushes. And I think it’s the same for writers with words and sentences.

With Vanity Fair, there’s this idea of pushing people to dream of something bigger and reinvent themselves. What do you hope people get out of your book? What do you hope it inspires them to do?

One is patience. With social media and influencers, the idea is that you can become rich and famous and successful overnight without really doing anything. But firstly, that shouldn’t be the goal. I would prefer if people instead wanted to do something good that lasts, and I feel like we’ve lost a little bit of that. You have to work hard and you have to be patient. And sometimes it’s a great thing to just shut up and listen for a little while. I also want people to be confident, to not hate themselves or beat themselves up, to be ready for another day instead of dreading it, which might be hard. I never set out to write a polemic on how to live your life or anything. It’s funny that no one’s asked me that question on what I hope people get out of it. I always assumed no one’s gonna get anything out of it, and if I just distract them from what’s going on in the world for a few hours and they chuckle a few times, that would be enough.