An Interview with Connie Willis

Words By Dani Hedlund

How long does it take you to complete a typical book?

I have a really long lead time. Right now I’m working on a story about Agatha Christie. She disappeared in 1926 and they never figured out what happened. I think all the explanations are terrible; they don’t fit her personality or her circumstances. The Agatha that comes through in her books was very different from the way the theories were trying to describe her. I think everybody bought her scam; the truth is she was Miss Marple. She was the smartest one in the room and she counted on you to underestimate her. But she was also not the vengeful person that some theories portray her as. The Agatha that comes through in the books was a wonderful woman. That rattled around in my head for years before I figured out a way to get around the obvious problem. I had to read all the books again to figure out what was going on.

I got the idea for Inside Job, which is about a psychic who accidentally channels H.L Mencken, when I was in Baltimore for the World Science Fiction Convention in 1982. I was a huge Mencken fan. I asked my taxi driver to take me out to the cemetery to find his grave. In the Acts of the Apostles it says the Apostles of Christ can raise people from the dead. I thought, “What if a religious group tries to raise a beloved member of their community and instead accidentally raises Mencken.” I did all the research but I could never figure out how to put the story together. When I was working on this story about a psychic I figured out how to incorporate Mencken thirty years later.

I occasionally write for a collection, I was asked to write for The Microverse; a book that published work by a scientist who wrote about an aspect of modern psychics or science alongside a piece by a science fiction writer addressing the same topic. I wrote At the Rialto and I think I wrote that in two weeks flat. That was an exception. Usually my novels take me a long time, Doomsday Book took me five years. It just depends what intervenes in the meantime and what problems I have with the story. I always miss my deadlines.

My process is similar to that of seat-of-the-pants writers. They just get an idea and go with it. I do that too but before I start the writing. By the time I have begun the story, I basically have my whole plot in place, or at least the beginning and the end, with a blurry idea of the middle.

Do you write the plot down?

I usually outline the plot but not in Roman numerals or anything: just notes. I jot down whatever occurs to me at the time. For instance, with the piece I am working on right now, I haven’t decided if it’s going to be a time travel story or a ghost story. I know what happens but I don’t know the mechanism I will use to make it all happen. A mystery has two stories; there is the story about what really happened, and then the story that appeared to happen. Of course, the detective’s job is to figure out how to get past the latter. In a mystery, everything must work like clockwork. When I wrote Lincoln’s Dreams the first time, it was originally a novella. Then I expanded it into a novel, but that was totally wrong. I had to write the story from scratch. I had to sit down and make a list of which revelation was farthest from the truth, which one was closest to the truth, and their order. Once I did that, it worked. That’s why my books take me so long. That, and I use all new characters.

Have you always written by hand? Have you thought of moving to typing?

I like writing away from home, at a cafe or at the library. My brain moves just about as fast as I write so I don’t need to go any faster. I want to be able to look at things; I want to cross something out and then look at the crossed-out part, see it, and then go “No, I think I like this one better,” or move this around and draw arrows.

I remember when the home computer came out and everybody thought it was going to revolutionize the novel: intricate novels with dozens of subplots and incredible interactions. I said “Like Les Misérables and War and Peace?” They kept predicting this huge revolution but I didn’t see it at all. In fact, what I saw was some really sloppy writing. In the old days manuscripts were blotted up with changes and white out. You can write any old piece of garbage and have it look gorgeous on a computer. People think that it looks done but it is often not.

You have had fifty years to see us grow through technology as a society. Are you impressed with how we have grown? Upset or surprised?

Ed Bryant, who was also a Colorado writer, described science fiction one time, he said “In 1898 any idiot could have predicted the automobile. It would have taken a true futurist to predict the interstate highway system. But it takes the science fiction writer to predict the traffic jam.” Science fiction’s biggest problem is that the futurists are convinced that their brains are going to be downloaded and they’re going to reach immortality in the next ten minutes. I had an interview just the other day and the interviewer said telepathy is going to be common technology in the next few years. He was excited about the possibilities but I asked “How is that going to be great?” What benevolent reason would drive the creation of such technology? There is only one, and that is to be the thought police. I don’t hate technology, I just wish people would try to figure out the unintended consequences. The first thing that probably happened when they invented the wheel, is that it ran over somebody’s foot.

I love the information age; my daughter lived a year in England before the age of the cell phone. She would stand at the phonebooth on Sundays at a certain time waiting for my call. Of course, we run into other problems: we can’t get away. Technology is basically amoral. The first thing people do with new technology is figure out how to commit a crime with it. I wouldn’t go back to the good old days, they weren’t that good. People certainly try to wax nostalgic about the fifties right now and that’s when I grew up. I remember reading Little Women and wishing I could go back to that time but my grandmother had no patience for that at all. She said “I have two words for you Kleenex and Tampons.” She didn’t even mention indoor plumbing.

You have written just about every genre I could list, including fabulism. What genre do you identify with?

My favorite thing in the world is romantic comedy. One of the first stories I sold was to Galileo Magazine. It was called Capra Corn. Those were the days when I used puns as titles. It was a romantic comedy about an alien checking out library books that were sort of universally overdue but he was doing it to get to know the librarian. One of the things that I love about science fiction is the freedom. In the mainstream world, the market is completely driven by the trends. When I read the science fiction collections as a kid, I got to read comedy alongside adventure story next to a very experimental story, next to a sad introspective story that could be on the pages of the New Yorker, next to a western in disguise, next to a romance. That’s why I really loved it. I love history obviously and time travel gave me a way to do history. I hate historical novels partly because I often question which parts are real. Time travel allowed me to talk about history while also avoiding all of that. In historical novels, you are stuck writing with what people knew at the time, which was nothing. We know nothing about our own time. The only people that are going to write well about the important issues of our time are the people who come after us. We don’t know anything, we are a bit too busy living through it. With time travel I get this parallax vision; I can have the outsider that has perspective but I also have the people who lived through it. I think that’s the way you should look at history. I guess time travel is my favorite, romantic comedy is my second favorite, and I get to combine those occasionally. Science fiction is so free, it’s an amazing genre.

The meat of your stories is always so intellectually rich, but most of the things you write have me crying/laughing because your style so warm and funny. How do you balance seriousness with your amazing sense of humor?

I read one time that literature is not supposed to teach you how to think, but it’s supposed to teach you how to feel and what to feel. Shakespeare could have written a very cold treatise on how old people should not try to control the younger generation but instead he shows us King Lear. That’s why we remember the serious parts of what he said. A lot of my complaints about science fiction and a lot of literature is that they’re busy being very distant. A lot of people will say comedy is about distance. I don’t agree with that at all. Satire is about distance. You can still really care about the characters in comedy, you can be afraid of what is going to happen to them. In a romantic comedy especially, even though you know from page one that they’re going to get together in the end, you still need one moment in the book when you are convinced that they are not. Getting people to care is the only way to show them the truth. We’re still lizard-brained people, we function through our emotions. Emotions don’t just drive us but they show us what’s right. We don’t only think it’s right, we feel that it’s right. Mostly in stories, you’re not sending a message, there are messages in it, there are certainly messages in Huckleberry Finn, but they’re not messages that can be encapsulated as a slogan or moral. The reason the message gets through is because you love Jim, and that’s why you believe that message.

Do you let the story choose its own length or do you try to force things into novels, novellas, or short stories?

For a long time I only wrote short stories. My first novel started off as a long short story. People used to tell me that I should try the novel because I could make more money and I would have space to fool around. I don’t agree with that philosophy. Every word should count. My favorite length is the novelette. The short story works for a world that is not too different from our own. If I were trying to set my story on another planet with another species, I wouldn’t have the room to accomplish that in a short story. In a novelette, I can develop strange worlds with a good plot.

Of the incredibly impressive list of things you have written, is there something you are most proud of?

The story that is dearest to my heart is Fire Watch. The biggest problem for beginning writers is that the story in your head and the story that ends up on the paper bear no resemblance to each other. With Fire Watch I was so driven. I had been to England and I had been to St. Paul’s Cathedral. I could not believe that this little rag-tag band had saved it. You see examples of the other all the time, when some insignificant nobody manages to kill a whole bunch of people. This was a story of small and insignificant people who managed to do something wonderful. That was the first time I had ever come close, not perfect, but close to doing what I wanted.

Now I think the work I am most proud of is Blackout for some of the same reasons. I was very driven to tell the story of these small and insignificant people that beat Hitler. Time Magazine was going to make Hitler the person of the century but instead they chose Einstein. That was perfect. Not only did Hitler drive Einstein out of Germany but the very people that Hitler thought were not worth anything were the ones that destroyed him. Einstein didn’t destroy him by viciousness but he did it with truth and science. Obviously, the RAF and the army played a part. I’m not trying to denigrate battles and wars. But Hitler was also defeated by shop girls, children, and old men, by debutants, and Agatha Christie. It’s so wonderful; in Hitler’s world those people were fodder, and yet they defeated him and his huge army.

We went to the Imperial War museum when I was doing research for the book because they had an exhibit on the Blitz. I told my husband to go look at stuff, I was going to be at least three hours. Ten minutes later he’s back and says you have to come with me. I go with him, very resentfully I might add. He discovered that it was a free day for anybody in the museum who worked through the Blitz. He found a group of old ladies who came down from Northern England. He bought them all tea and cookies and sat them down so I could interview them. He earned a lot of husband points that day. I think I asked one question and they just kept talking. They were so funny! They had driven ambulances, driven canteens, they had been ARP wardens, they had been rescuers, one woman worked with bombs. If you saw them you would think they were a bunch of old church ladies; they had hats, gloves, and they were dressed up for their day out. They laughed the entire time and I’m going “I had always thought of the Blitz as a rather grim time but you make it sound like it was fun.” But it was! They were young, on their own in London for the first time, and there were men. One woman said hardly anything. When the rest wound down I asked her what she did in the war. She said “Well until two years ago I couldn’t tell you.” She worked for intelligence in the war, and her work had just been declassified. I tried to put how much fun they had in my book; they talked about men, they borrowed each other’s dresses. It was an adventure.

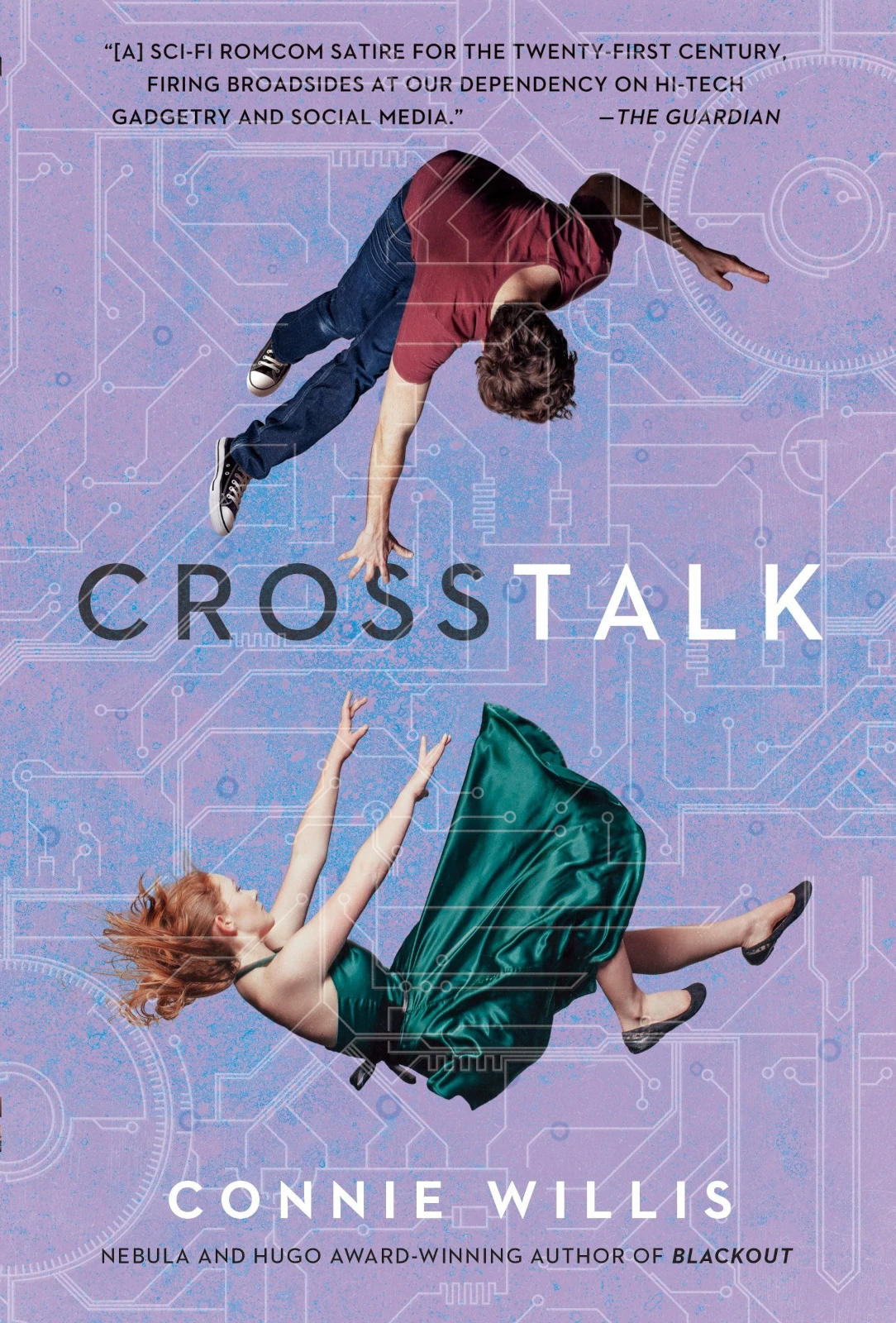

Let’s talk a little bit about Crosstalk, your new book that came out last year. You explore really interesting ideas about connectivity. Talk to me about the process and your inspiration.

It had multiple inspirations. I was on a panel about telepathy in a convention. I was declaiming about what a terrible idea telepathy was. People’s thoughts should not be made public. This awful moderator turned to me and said, “Connie, when have you thought something and not said it?” I thought “Right now, this very minute.” That was one of the first glimmers. Then there was the Mel Gibson movie What Women Want; it was the worst movie I had ever seen in my life. The movie got telepathy all wrong. I was also inspired by watching people interact with their phones, with Skype, reading Dear Abby, and the online equivalent of Dear Abby. If we have all this communication you would think our relationships would get a lot better.

Those were some of the things that inspired the book. What makes a relationship. Little tiny ankles and demureness was supposed to make a happy marriage in the Victorian age. In the fifties it was “Nice girls didn’t.” I remember thinking on dates “Don’t ever let him know how smart you are.” Nowadays we have totally different ideas about what makes a good relationship, but we still have just as many terrible relationships as ever. In my experience, good relationships don’t come from “We both like red wine and Italian movies.” They come from when my grandmother was in a nursing home for three years, my husband went to see her every day. That’s what makes a relationship. I guess that’s one of the messages in the book, you have to be willing to care more about the other person, more than you care about yourself. There are things you value more than just your own feelings.

Since you started in the seventies, how has the industry changed?

Science fiction was really little when I started. It wasn’t as little as it had been before, I got there at a midpoint. Science fiction as a field was basically one large conversation. Robert Heinlein wrote Starship Troopers and Joe Haldeman said “That’s not the way the war is” with The Forever War; then William Tenn says that’s wrong with The Liberation of Earth. It was a great period, the size allowed everybody to talk back and forth. In the seventies we kept thinking science fiction was dying. It’s been that way since the first day I entered the field until now. Then we had this huge boom and everybody was very rich for a short period. Now science fiction is huge. It’s had the effect of splintering into subgenres: military science fiction, paranormal romance, alternative history, steam punk, etc. The industry has become more professional and more serious. It used to be an amateur’s game. Once big money got involved it changed in nature: branding. If you write one time travel novel, then you won’t write another genre ever again. I actually had excellent advice on that when I won the Nebula and Hugo Awards for Doomsday Book. Charles Brown of Locus Magazine was a good friend of mine. He took me aside and said this book has been really successful which means if you write another time travel book after this, you will be trapped in the time travel subgenre. I would suggest that whatever you do next, write something else and then you can go back to time travel. I wrote another time travel novel, three short novels, Bellwether, Remake, and Uncharted Territory, all of which were very different from each other. Then I wrote To Say Nothing of the Dog. I think that was excellent advice.