An Interview with Billy Simms, Creator of Craftowne

Words By Andrew Jimenez, Art By Billy Simms

This interview accompanies Craftowne, a visual novel that we are serializing here on F(r)iction Log. Read about the genesis of the work and Billy’s future plans.

Andrew Jimenez (AJ)

What is Craftowne? Should we call it a visual novel, or a comic?

Billy Simms (BS)

I did Craftowne as my thesis show at Miami University and, as I was planning it, I realized that really this is a comic you can walk into––but then a lot of people didn’t like to use the term “comic book”, so I decided I needed a unique term to describe it. “Graphic novel” is kind of it, but it’s more “visual art.” So I coined the term “visual novel” to make a unique thing for it, because I feel like Craftowneis a unique thing itself. A lot of Craftowneis very kitschy, trashy stuff, but I love it. I would say one of the major influences of Craftowneis MAD magazine.

AJ

How did the idea for Craftowne come about?

BS

First, I’d like to say that Craftowne is a work of fiction, and any relation between people real or fictitious is completely coincidental. That being said, I did run into someone that I grew up with and we got to talking about the town we grew up in, and that got me thinking about towns and communities and all the eccentric people that can be there. All communities are kind of the same, but also kind of different. There’s a uniqueness to them, but then there’s commonalities. I was interested in the personality of places that you get from the reason that the place exists, whether it’s a college town or near a factory. I met someone whose town was right next to a tampon factory, so that’s where everyone’s parents worked.

Originally, Craftowne was going to be woodcut prints, but then I realized that some of the text I was writing was not going to make a good woodcut—or I didn’t think I could do the woodcut the way I wanted to.

It took me a good six months to get started, but once I finally decided to do the text is when Craftowne really took off. The stories I wanted to tell were just too complex to tell solely in images. The narrator as a character also pulled it all together and gave the individual stories cohesion.

AJ

Did you always expect it to be an exhibition first? How does executing an exhibit differ from planning and executing a visual novel?

BS

Yes. I was in graduate school for my studio art degree, so I was working toward an exhibition. The way I think of the exhibition part of it is that it’s a comic book you walk into physically. Rather than an object in your lap, you walk through page to page.

There was actually a soundtrack in the gallery, too. I used popular songs in the 70s and 80s and looped it on “Craftowne High School Radio.” A DJ (me) came on every now and then to talk and make references to the events of Craftowne. I used sixty songs and each one connected to a story in the show somehow—I used Ray Stevens’s “The Streak” for the Streaker, and “Highway to Hell” was the one for the thirteen kids killed in the car accident.

AJ

For the exhibition you had all of these physical pieces that you created. What did you end up doing with those pieces? Did any of them make it into the comic itself when you transferred this story from the visual space into the comic?

BS

Yes, quite a few of them are in there actually. The one about the Indian catacombs is there, as is the vodka bottle on the back of the comic. The images that you see in the comic are actually sculptures I made. For the vodka bottle I made my own Craftownelabel for it; I thought that creating the object worked better as a sculpture rather than doing a woodcut of the bottle. For the Indian catacombs I molded a Ken doll and put plaster of Paris all over it.

Something you don’t see in the comic, because it just wouldn’t photograph well, is the model of the town. It was seven feet by eight feet and had 2,500 3D-printed houses the size of Monopoly pieces. I don’t even want to know how many trees I laser cut in two parts and glued together—it had to be about 5,000 of those, easily. That’s why I had to draw a map of the town, because the model is too big to photograph and tell what it is.

AJ

Was there less text in the exhibition than there is in the comic?

BS

No. One thing I was actually pressured a lot about was text and taking some away. I stubbornly stood by that and it was all there. It was all in my handwriting on paper, mounted on the walls like separate pieces—and people would go and read it! I did the comic version of Craftownebecause I was afraid people wouldn’t take the time to read everything in the gallery, which turned out not to be true. But I’m glad I did the comic anyway.

AJ

Your prose style in the comic is really engaging. It has this off-the-cuff aspect to it, but it really works, and the voice is very distinctive.

BS

I owe a lot of that to two people who helped me to edit. One is my wife, the writer Margaret Luongo. The other is a friend of mine in the English department at Miami University, Keith Tuma—he really helped. I assumed by working on the text I would give him text, he would give me feedback, and I would rewrite. But, what would happen is I would send him text and he would send it back after just cutting stuff. You think there’s a lot of text now, you should’ve seen it before. He [Keith] was brutal, and it’s what I needed.

AJ

Your work has been described as the intersection of visual art, literature, and theatre. What led you to mix these artforms into a conjoint presentation?

BS

Well, I should have to say that it’s only been described that way by myself, and I described it that way because those are the things I was trying to mix together. The visual aspect is grounded in studio art—printmaking, sculpture, and crafts, even. Then there’s so much text, it ends up being a piece of literature.

My background is in theatre, and I think of the gallery presentation of Craftowneas something of a performance piece. The actors are the other people who come in the exhibition; they’re the people in the show. A lot of the aspects are interactive, like the nudist disco part, for example. You can move the people around and there are different pictures you can put on the wall. The idea that people are actually doing things in the gallery space—playing the card game, drawing disguises on the flasher—was really fun to plan out. I think I can probably do more with that in the future.

AJ

What advice would you give to fledgling artists and writers who are interested in the intersection of different traditional forms?

BS

Well, I’m not sure that I’m not a fledgling artist myself. I think my biggest piece of advice is just to read and watch as much as you can, and not just necessarily what interests you, but other things that are good—sometimes even things that aren’t good, because sometimes those not-good things can be influential.

It’s easy to get sucked into only doing the kind of thing you’re interested in. I run the visual resource center at Miami University now, and every now and then students will come down and hang out, and they’ll tell me, “Oh, you need to watch this manga video,” or, “You need to watch this thing.” And the stuff they show me is really great because some of it is really, reallygood but it’s not stuff I would’ve found on my own. I feel it’s keeping me young.

AJ

What draws you to the graphic storytelling medium?

BS

The answer to that goes a long way back. When I was a kid my family was full of big readers, and I actually had a lot of trouble learning how to read. There’s a piece in Craftowne—the miniature school piece—that symbolizes that. Learning to read…it was all phonics back then. To this day if you give me a made-up word that I’m supposed to sound out by looking at the syllables, I cannot do it. I have a degree in special education; I taught school for ten years; I just can’t do it.

What got me really into reading and helped my reading a lot was comic books. My brother bought one on vacation and then I started buying them. I still have every comic book I’ve ever bought—the first one was a copy of Heckle and Jeckle from 1976. So, I just loved comics, but I kind of got away from them for a long time until my wife and I moved to Ohio in 2004. A lot of my wife’s graduate students were really into them, so I started picking back up reading—not comic books, necessarily—but graphic novels. And I noticed how much more sophisticated comics had grown in the years. I just loved the form, and I think it’s really good for struggling readers, as well as for solid readers who just want to experience things a different way.

AJ

What do you take into consideration when determining what type of artwork to use when you’re telling a story?

BS

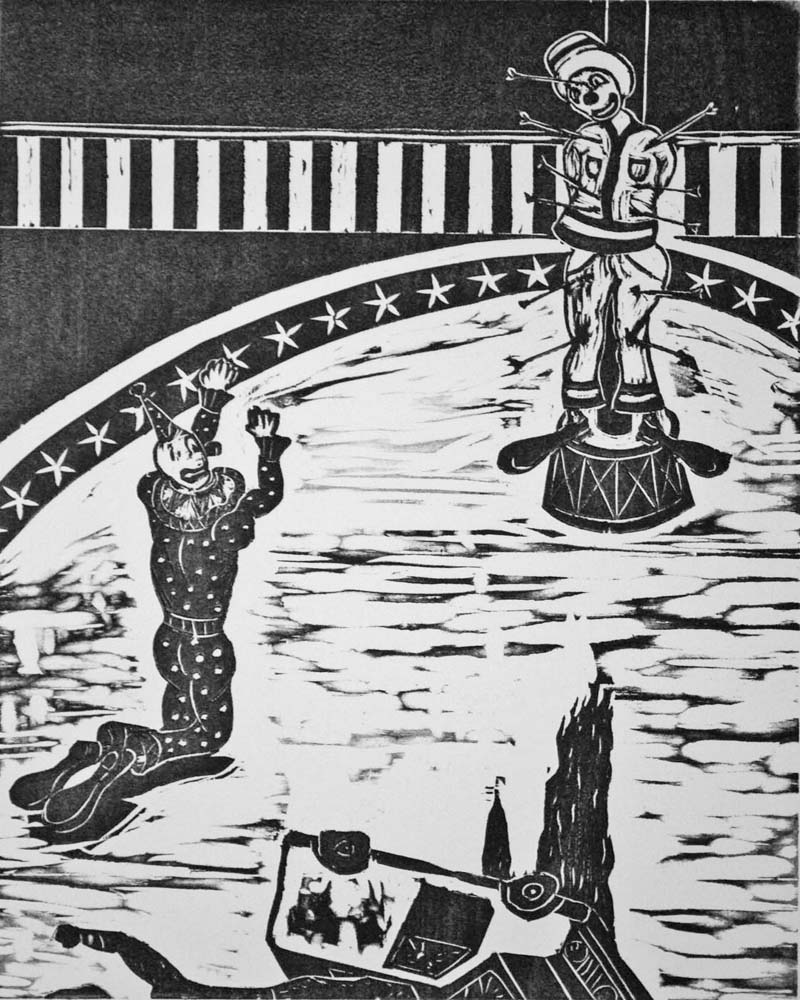

Mainly I start with printmaking and woodcuts, because that’s what I’m most comfortable with. I did a novel in woodcuts. These were popular in the 20s and 30s; they’re just single-page images carved into woodblocks that tell a linear story. My wife studied one in graduate school, and I decided I was going to do one. So, I made a forty-two-page woodcut novel. It’s called Clown Genocide. It’s about clowns getting massacred; it’s a metaphor for genocide.

AJ

You mentioned earlier that you have 3D printed some things. Did you have access to a 3D printer through the university?

BS

I did—I could pay to use one. I made the houses that way, and the other things that I 3D printed were the carnivorous fish of Craftowne. I made three figures of them in a bronze-casting class I took, so then once I made them out of bronze, I was able to scan them in and 3D print them. There are about twenty-five of them in the show, nailed and crawling all over the walls. I financed them to be about twenty dollars apiece, so people bought them ahead of time, and once the show was over, I gave them to everybody who bought one.

I also made one big fish—he’s like twelve inches by fifteen inches. He was in an aquarium, meant to look like a bad science exhibit. No matter what I did, though, it kept coming loose and floating to the top, so finally I just poured concrete into the bottom of the tank—so it’s never coming out.

AJ

Was that your first time using a 3D printer?

BS

Yes—but I didn’t really useit at all. There’s a really great guy at the university whom you tell what you want, he gives you a price, you approve it, and then basically you’re in the queue for printing. Depending on when you place the order determines how long you have to wait for it, but they take care of it all for you. It was really great; I would get plastic bags full of 250 houses at a time and I’d spend an afternoon gluing them all over Craftowne.

AJ

Would you use a 3D printer again?

BS

Absolutely. 3D printing is really nice. Especially if you want to make multiples of something, it’s a really fast and convenient way to do it—and it’s not terribly expensive.

AJ

In addition to comics, you do everything from making hats, woodblock prints, and designing lights for plays. How do you keep your creative fire stoked with so many types of projects?

BS

I just enjoy doing all that kind of stuff, and one is a break from the other. I got into hat making and bronze casting during an annual program Miami University has called Craft Summer. Since I spend so much money buying hats, I started to make my own. And I’m branching out—I’m working on my first pillbox hat, as opposed to just baseball caps. We’ll see how it comes out. I was sewing before you called. My undergraduate degree is in theatre, and after graduate school I needed to make sure I earned some money. I was never really happy with the way I did lighting design (the last time I’d done it was twenty years ago), so I wanted to go back and see if I could do it better.

So many of the people I know that are artists don’t say they’re artists first. They say, “I’m a painter,” or, “I’m a photographer.” I just say I’m an artist. I come from theatre and in theatre you decide to do a show, and the show requires whatever it’s going to require, and you figure out how to do it. We did a play in college that was supposed to look like a bomb had just blown up—so we figured out how to mix concrete and we sprayed it over the whole set. You just do what needs to be done, and you don’t worry about “I only work with wood” or “I only do this…” You just do what you’re supposed to do, and I think that helped me.

AJ

I would imagine those kinds of challenges, when they present themselves, would lend to a lot of creativity.

BS

Oh, yeah! You really have to solve problems and you’ve got to budget considerations. In fairness I rarely had to actually be the one solving those problems; it was the faculty members doing it. But, I kind of got the trickle-down effect and see how they would go about doing things like that.

We had a designer from Europe, and they approach design very differently there. I’ll never forget the time we did a production of Beauty and the Beast. In the first scene there’s a bear on stage, so they [the faculty] were talking about the costume for the bear, how the actor should portray the bear, etc.—and this designer just couldn’t understand why we couldn’t have a bear and just keep it in the shop. She was completely serious because that is what they were doing in Europe. You know, if you have a play with a bear, get a bear! There was a lot of culture clash.

AJ

You mentioned this earlier, but you hold a BA in theatre; that’s where you said you got your start. How did that study affect your goals as an artist and the trajectory you ended up taking?

BS

I think there are really two ways it has done that. One is complete accident. I went to the University of Maryland Baltimore County and I just joined the theatre program and got involved. I had no idea that it was nationally considered an avant-garde theatre program. Everyone else was doing Music Man and Cabaret,and we were doing the third production ever of Gertrude Stein’s Listen to Me and Beckett. We were doing all this weird, weird stuff…so now when I go to see something and everyone else is like, “Oh, that’s so strange!” I’m just like, “Oh, yeah that’s kind of like a Beckett thing.”

So, I feel like I just got exposed to and taught things that most people don’t really get taught in-depth, and I feel like it really informed my aesthetic. I came from this sort of kitschy, MAD magazine-based aesthetic and then I was studying Beckett, and it all came together in a way that I think works really well for me.

AJ

You’ve found a lot of different residencies—Artists in Action, Arts in the Park (a teaching residency). How have residencies helped build your career, and can you offer an insight or advice for winning a residency?

BS

I think part of winning residencies is just being willing to go for it and try; they’re hard to get but you never know when you might get one. You never know what’s going to happen. I’ve applied for a lot, and only gotten a couple. I did get waitlisted for a couple, or got nice letters and things like that, so you just keep going and eventually something has to work out.

The Arts in the Park residency is really wonderful program in rural Indiana and Ohio. It’s funny because it sounds all fancy as you’re the “artist in residence,” but what you do is you go to parks and you teach kids art. So that’s really what you’re doing, and then you have time to work on your artwork in the evenings.

The Artists in Action residency in the Annmarie Sculpture Garden & Arts Center was really fun. They give you a booth area and you just work in the gallery all day. That was nice because as you’re working people are coming in and out and you get to talk to them about your artwork as you’re making it.

AJ

Last year you participated in a panel at AWP. What can a first-time attendee to AWP expect, and what are the benefits of attending such a conference?

BS

The best thing is the panels, but just going around and talking to people and the vendors is really great. The biggest thing is to not be shy—meet people and talk to them. It seems to me that a lot of people just go because it’s what is expected of them professionally or they have a panel. I think, take advantage of it! There’s a ton of interesting stuff there, so just go do it.

AJ

So, now Craftowne is going to have a third life online, on F(r)iction’s website. What do you hope people get out of the experience of reading it?

BS

It’s interesting because reading a comic on a computer screen is different than reading it on paper. I’m hoping, really, that it reaches a broader audience. I hope people just enjoy and connect to it. When I set up Craftowneat the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, I had people track down my Miami email and contact me about it saying they enjoyed the exhibit—that universality it great.

AJ

With so many different skills and interests, what do you plan on tackling next?

BS

The next big thing I’ve been spinning my tires with is a continuation of Craftownefable. I’m working on a story that has seven characters, all of whom live in Craftowne. Near the monument of Craftowne—that mysterious monument that no one knows the origin of—they find what they come to realize as religious artifacts, and they try to re-enact a ceremony. It’s basically an orgy. They have visions, and I’m doing a series of shows about these characters and the work that they create attempting to capture these visions. I kind of like the idea of this town that has an element of supernatural.