An Interview with Bethany C. Morrow

Words By Bethany C. Morrow, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

What inspired you to write A Song Below Water?

Oh gosh, nobody really likes the answer. I’m like, all of you! I was on Twitter, in the DMs, with my sister, Jennifer, and I said my voice is power. I was saying it as a sort of hey, can we do some truth-telling, because what we were watching on the timeline was a Black woman being completely abused and attacked. This Black woman had expressed an opinion—how dare—and all of these people dogpiled her. We know why this happens. It’s not because we’re powerless. It’s because our voices are power and that pisses you off. So as soon as I said the line my voice is power to my sister, I was like that is something that a siren would say and that is something only a Black siren would say. And that was when I knew I would write a story about sirens who were only Black women.

You could have written this as creative non-fiction, you could have written about it in the real world. Why did you choose to bend genre around it?

If I wrote non-fiction, I am only talking to the white people who think they already know better. There’s a reason this is young adult as well. I’ve written adult fiction. Young adult is specifically when I’m speaking to a teenage Black person. It is a love letter specifically to teenage Black girls. Are other people welcome to read it? Anyone can read it but it’s not to everyone. So if my target audience is Black girls, there are a couple of things I need to do. Number one, I need to give it directly to them and not have it be an academic text. The second thing is while speculative elements allow me to illuminate a truth, they also help me alleviate the burden of the person who does know already that this is real. It gives them just enough acknowledgement and recognition without also pressing down on the wound. And that is a great tradition of specifically Black American speculative fiction authors, is using fantastical. If you woke up tomorrow and had my experience, it would be fantastical to you. So the only way to tell the truth about my experience is to use speculative elements. Having always read and been familiar with genre-blending Black American authors, and specific to our diasporic group and identity, that to me is home and that just makes the most sense.

I feel like you are balancing two enormous responsibilities—one of them, of course, is to talk to a community that you directly relate to, that is wildly underrepresented, that doesn’t have voices and representation to make them feel that there are other voices like them. You are balancing a huge history with very personal evidence while of course trying to balance a new demographic. How, as an author, do you approach all different perspectives that you are trying to balance in one text?

I don’t balance it. So we know about code-switching, right? You probably have never heard Black people talk to Black people. When you pluck people of color out, and you put them around you, they are code-switching. You are hearing them talk, fluently, to your perspective. I know exactly how to get along in primarily white spaces, particularly American spaces because it’s my life. I am 100% fluent in white-centred American culture. I don’t have to do anything, therefore, to speak to it. Basically this book is an invitation to people who otherwise would never hear us speak amongst ourselves to listen. It’s literally giving you one of those aluminum can telephone things and saying here, you can eavesdrop. This is for you. We are sometimes going to be speaking in a way that’s completely familiar to you, number one because they are in primarily white spaces a lot of the time in the book. But you’re also going to hear these characters speak when it’s just them, in their home or whatever, in ways that will be less familiar because you are not privy to that dialect. I tell people that instead of engaging in these conversations that allow people to constantly put the burden or the responsibility on you as the non-white creator, just understand what it actually is. It’s illiteracy. I don’t write as though I’m writing to white people.

So how does that work in a publishing industry that has been predominantly white male since the history of American publishing?

I have to be very intentional about where I shop my work. I personally do not code-switch in publishing. So I speak very plainly and I’m very unapologetic. I’m also just willing to say no. And that probably categorizes my entire career. I’m not going to risk who I’m writing for, I’m not going to risk myself, my liberty, my community. So the very beginning of my career was dropping out of an offer of publication—which wasn’t great in the first place, and then leaving an agent and finding a different one. Some people will say you just have to go with it sometimes, but you don’t say that about something as important as my identity and proper representation in an industry that I know has such a cultural impact. Why would I be willing to indite the culture that I live in in my work and not be willing to indite the apparatus through which I have to present my work?

I am so interested in the fact that when we are introduced to your two main characters, they are so timid. How did you write a story about being afraid of nearly everything?

I have sisters, and I have a lot of siblings. I wouldn’t have known that I wasn’t the norm if I didn’t have siblings. Growing up, I watched the process that other people went through. One of my sisters is very dark skinned and she had a completely different experience at different schools. We were always at Christian schools, we were always the only Black family in those schools, and her experience, even with people knowing that we were all from the same family, was still observably different. So at some point you stop looking at your sociological response to things and you start recognizing what is the desired outcome.

Effie, in particular, very closely resembles my sister Jennifer. I was hoping to cowrite with Jennifer, and originally she was going to write Effie. She has five children so that didn’t happen, but I really modeled Effie off of her, which again was part of the whole idea behind how Effie looks to the world and how she actually looks to Tavia. She’s really funny and really sardonic and has this snide kind of wry humour that other people don’t see. All they see is that she’s a super anxious person. And she is, but she’s not just that. I don’t think it would do a lot of good to make a bunch of characters like me.

What was it like to balance these two different perspectives? How did you manage to make them feel distinct?

It depended on what I know from having sisters. The thing about having siblings is that, if Anastasia, Jennifer, or I call my dad, he’s going to ask who is this? We all sound like each other when we’re together, but everybody has their particular accent, I guess. It was really important to me not to have everybody in the book be completely distinct, which you get a lot of push-back for, especially in YA. But it’s not realistic. These people spend every day together, they’re sisters, they’re going to be distinct, but they’re not going to be completely distinct. Again, if I call my dad, he’s going to think that I sound like one of my other sisters. That’s just the way we sound to people. So I wanted them to have more pentameters or melodies in the way that they speak, sometimes word choice, because there are little things to differentiate the words they might choose, the way they might joke. With Effie, the way that she speaks isn’t as melodic, it’s not as fluid as Tavia’s because she does have a lot more anxiety and she just doesn’t have a really strong footing. So her confidence really comes when she’s with Tavia. Tavia’s the only person who knows that she’s funny, for instance. I tried to think specifically about who they are as people, where they are in their journey, and their self-identification, because the difference for Tavia and Effie is that Tavia knows who she is. She’s trying to navigate a world that hates what she is, but there’s a very different phenomenon when you don’t even know. And so that, to me, impacts the way that they express themselves as well.

We have these incredibly strong main characters that have trauma in their backgrounds which haunts them throughout and slowly comes up in the narrative. What was it like to create these kinds of backstories that would give you the narrative devices you’d need going forward?

A lot of Tavia’s stuff came spontaneously. I also just really liked the keloid. I liked it as a device to show the intentional choices that her parents made for her and the way that allows you to start dealing with generational trauma and the sort of disconnect between wanting to protect the next generation but also going as far as to sort of imply that their safety is up to them. In so doing, you erase the violence of the system itself. Of course, it’s coming from a place of wanting the person to be protected, but what about the trauma that you’re doing? What about the trauma that you’re imparting by taking and giving me this story and assigning this story to me that isn’t true. There’s a passing story in this book, where she’s passing for someone with an assumed disability. I have a family history of passing, and I know why people pass. You don’t pass if you don’t have to. You don’t pass if your life doesn’t depend on it in some ways. So the same is true of her, because the thing that she is trying to hide is something, again, that is specific to Black women and something that is aggressively disliked and punished by the power majority.

So talk to me about world-building. Tell me how this world came together.

The Sirens came first. And because this isn’t a story of people without power, but people who have power that is not allowed, then obviously there has to be somebody with power that is allowed. Because that’s what the world is like. So that’s where the elokos come in. Their power is white privilege. We see that it has no other purpose in the story and doesn’t really do anything except make people like them and treat them nicely. A lot of people asked why I would choose the eloko. It’s because I’m decentralizing Europe in fantasy. Even the spaces that are considered staples in European fantasy, I take back. So mermaids don’t really spawn above the equator. This book is very much Black American fantasy. It’s very specific to my diaspora experience, and that involves a telephone effect with things from the continent. Being native to the west coast, I don’t have these very romantic and thick ties to the South, and therefore to whatever culture people think is direct from the continent. I really wanted to deal with the fact that by the time stuff gets all the way to the west coast, evolutionarily, it’s a story that’s been told and retold and retold and retold. I’m not trying to tell you that this is the original story. I’m actually telling you it’s not, because there’s nothing invalid about the diaspora having our own version of things. It’s as valid as any other oral tradition, any other type of mythology. So I’ve intentionally taken the elokos.

So, why do the elokos become the top of the food chain, in terms of the fantastical identities? Because white people can be born elokos, obviously. Whiteness as a construct is not a diaspora—there is no nation from which it hails. It is literally created solely for the purpose of power conglomeration and subjugation. So when you’re talking about that identity for what it actually is, and the fact that it isn’t a heritage, the overarching quality and characteristic is greed. I need to own everything—everything needs to be accessible to me. If it isn’t, it is evil. It’s Manifest Destiny. If I can’t have something, it’s wrong. And that thing needs to be snuffed out. So you take something that has as chilling an actual origin as the elokos—ancestral spirits, cannibals who live in trees, and use these bell sounds to trick people into the forest and then eat them. It’s the mythology of mythology. So, sure, these people started out as cannibals. Doesn’t matter, we love them to death. What about Sirens? I make things intentionally wrong. Like obviously, in reality, if you were to pluralize eloko, it would be Biloko it wouldn’t be elokos, and obviously probably white people wouldn’t be Biloko. To talk about why they have such good intuition and stuff, I still credit it to ancestral spirits but not THE ancestors. Just like, your ancestors. Just like, anybody’s ancestors.

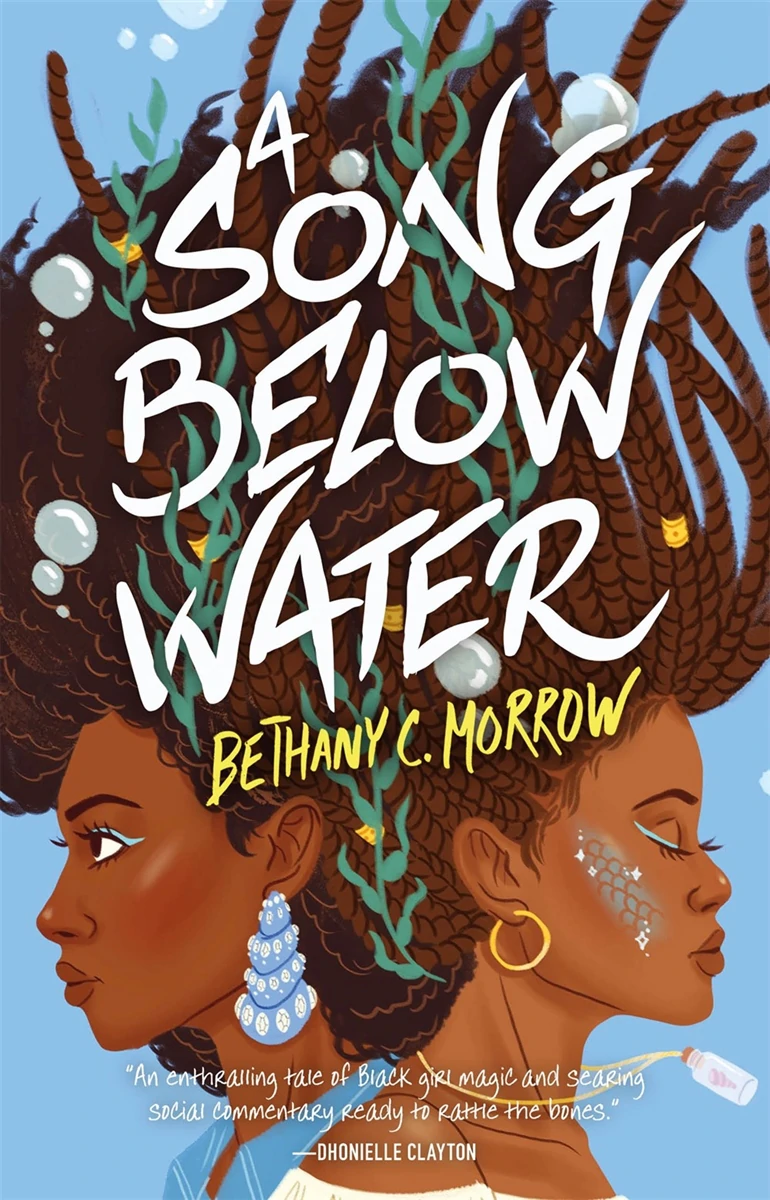

Have you seen the cover of A Chorus Rises? The follow-up is not a sequel. I wanted someone to be able to read it and enjoy it without having ever read A Song Below Water. But if you did read the first book, you would know who Naema is, and the second book is Naema’s story. Yes, it does chronologically follow A Song Below Water, but it goes even deeper into uncovering and just inditing misogynoir, because people were very quick to hate Naema. They called her the antagonist in the first book. She’s a 16-year-old high schooler. You know that the antagonist in this book is white supremacy, right? All of the things that happen to make their lives miserable don’t come from Naema, they come from the society that they live in. I just want to deal with what it means that these were the two Black girls that you guys could understand liking. And then this Black girl, Naema, who I will tell you, is the most “like me” main character I’ve ever written hated her, you just hated her. When my publisher bought A Song Below Water, it was a two-book deal, and I had said that the second book wasn’t going to have anything to do with the first. But then I came back and said, just kidding! Some bitches on the internet upset me! So I’m going to be writing about it.

Most of our readers are writers. Talk to me about the publishing experience. Have you always wanted to be a writer?

I always was a writer. I didn’t know what the steps were. And there was a time, truth be told, that I wanted to be an urban planner. But I was always writing. I always had a five-year plan. It’s not always been the same, but I’ve always had a five-year plan since I was in fifth grade. I had no idea that there were steps to publishing. My child brain just thought one day I’ll be published. When I was in junior high, my family was obsessed with Star Trek, and Voyager was a big thing. We watched it every week as a family. One day, we were watching Voyager with and it said episode written by Elizabeth Stanley, and I lost my shit because that was my teacher’s name. So I went in to school the next day and I slammed my hands down on her desk. And I asked do you write for Voyager? And she looked so terrified. She said… how did you know? I told her that I watch it every week. I said that I write too and I would love to write for Star Trek. She said that she’d teach me how to query an agent, so she started a writing club for me after school and other people joined, but that’s literally how it started. She said, okay, well if you’re going to write for Star Trek, you have to know how to address your letters. And this was all, obviously, when everything was snail mail and there was particular formatting and the way to fold the envelope and all of this stuff. That’s really when I realized that there’s a whole industry behind this. It was very formative. It also was really great because I knew that I wasn’t interested in studying creative writing, because they weren’t going to teach me how to write like me. It turns out, a lot of those programs don’t teach you about the industry anyway.

It took me straight five years to get an agent. From 2001, probably, I was querying here and there. But by 2009 everything went online, and suddenly there were all these agents who were really extensive and consistent blogs, so you start seeing that everybody’s white. And you start realizing that there are people who are really honed into a particular genre, and that a huge part of the hurdle was sending it to the right person in the first place. When things went online it definitely changed everything. I don’t think I ever got more than 5 requests, let’s say, between the year 2000 and the year 2010. And then in the first three months of querying electronically and directly in 2010 I got five requests. So it really works when you know who you’re talking to. You can also actually track in real time what they’re doing and what they’ve recently sold.

There are also a lot of conversations that, as a Black creator, you don’t realize other people don’t have to have, which makes you appear difficult in publishing. Most people don’t have to go back and say I never said she was light-skinned—why is this character so pale on the cover? Or oh, you keep correcting this, which is an “ism” that we use in the Black community—stop correcting. This isn’t an error. Just constantly having to tell people that they have an internal bias that treats things that are true to me as being stylistically wrong and so I have to keep saying something to them about it. Even if your particular editor is great, which obviously I wouldn’t work with anyone who isn’t, people will make ridiculous suggestions. Sales will make ridiculous suggestions, they’ll want to change things so that they sound better, and I have to ask to who? I know who my target audience is. It’s constantly wrangling your missions back from them, constantly wrangling your target audience back into the centre. The unpaid work that they ask for is also absolutely ridiculous. I have a Black publicist, Saraciea Fennell at Tor. We make sure that we are prioritizing Black reviewers and Black bloggers and Black events and book festivals and stuff, and making sure that it actually gets to the people that I want. Saraciea recognized how tiring it is. So she would say, this is a question that Bethany doesn’t want to be asked again, this is something that she’s done a ton of interviews on at this point, you can review this—she doesn’t want to have these discussions anymore. Just her understanding of the emotional labour that would come from having to explain the basics—especially in the month of May and June—was almost like, every other day if not every day. For people who want to be writers and people who want to be traditionally published in particular, and who are people of colour, specifically Black women, you have to find your community within the community, or they will suck you dry.

Are you exhausted every time you feel like you have to explain your entire book to people it’s not aimed at?

I do honestly trust my team at Tor. They know me. So they will tell me if it’s an outlet that should be fine for me. Then other places they’ll say that it’s probably not a good fit. And there are also times when, if they are unfamiliar with an outlet, I get the questions ahead of time, and I’ll be able to say no. Or they will send me previous interviews, which is what they did with this. I don’t ever just go in blind. I can’t afford to do stuff like that, because then that’s made to reflect on me. For everybody else, they’re at work, but for me, we’re talking about things that are literally contested issues of reality that are specific to my lived experience and identity. It’s not the same workplace for me. For the Black people I know who have very different personalities to me, I tell them that you have to be willing to say no. You have to be willing to say stop. For everybody else, it’s this isolated incident. It’s not for us. You can’t let people treat these infractions like they are one-offs because it’s the first time that person said something stupid. The impact on you is going to be very different, and by the time you get fed up, you’re going to be past the point of burnout. And that’s not fair to you, because that is going to impact your career and your productivity and even, for a lot of people, your desire to even do this.

We started this conversation by talking about this idea of actionable plans and actionable change. You wrote an incredibly powerful book. What actionable change do you hope occurs from the people who read this book?

I am going to give you my absolute knee-jerk response to that question. I’m not going to give anyone directions, because that negates what I am asking them to do, which is to engage with the text and themselves come up with an action plan as opposed to me, a Black woman who wrote the book, further exhausting myself to give them ideas. You’re in your seat of privilege. I’m not. You should actually have a pretty good idea of ways that you can affect change in the society that you’re from.