An Interview with Benjamin Percy

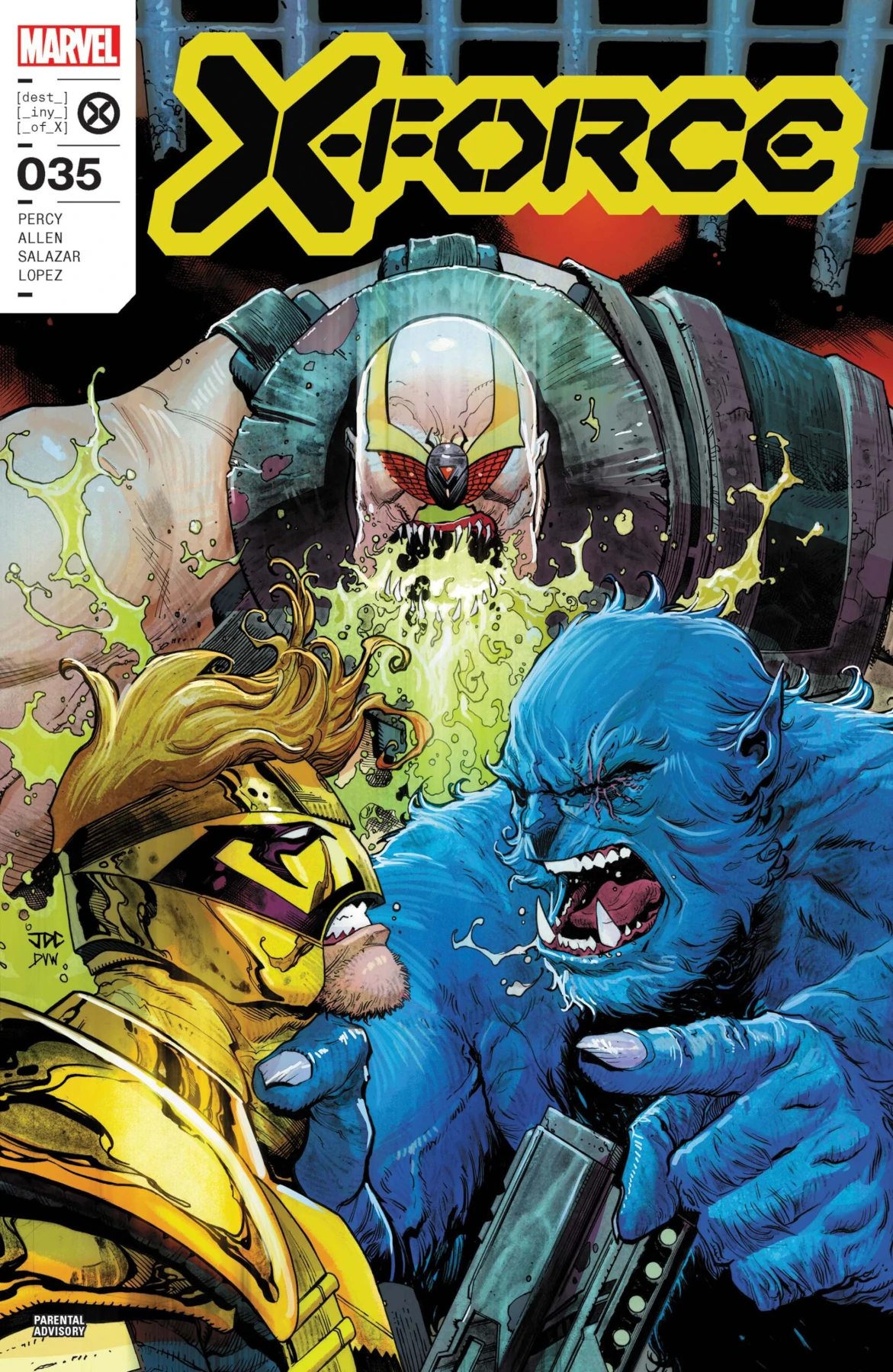

Words By Dominic Loise, Art By Joshua Cassara

Over the decades, we’ve witnessed different versions of the X-Men Beast’s (Hank McCoy) physical changes as he continues to mutate and shift with Hank’s personality. With the nature of comics today, creative decisions and changes to a character comes with the collaboration of different writers and artists. How did creators Stan Lee and Jack Kirby lay the foundation for Hank McCoy in X-Men #1 (1963) with Stan’s verbose, brainy dialogue and Jack’s drawing of Beast’s bulky physical presence?

It’s a wonderful juxtaposition (that would later be improved upon). The brutish appearance and the erudite manner.

I’m thinking of other fictional creations that use a similar technique. Think of Patrick Bateman in American Psycho for instance. He wears expensive, tailored suits and fusses over his face and hair with every manner of product and eats in white linen restaurants…and he also spends his evenings engaged in blood-splattered extracurriculars. A torturer, a murderer.

That startling contradiction is what makes Hank so much fun. You never quite know what to think of him. He might be quoting Homer or Shakespeare, but we’re still worriedly studying him out the corner of our eye, waiting for him to break our neck with a hard kick from one of his Fred Flintstone feet.

The seventies Bronze Age is a beloved era for Hank McCoy fans. He joined The Avengers, experiences a classic bromance with Wonder Man (Simon Williams), and gets more playful banter with catch phrases like, “Oh my stars and garters.” Hank also droped his human-life appearance for his iconic blue fur look. Do you feel this change in appearance and being in the public eye with The Avengers influences Hank’s increase in people pleasing syndrome, where the individual wishes everyone to be happy and sidelines their own needs?

Bouncy Beast is always how I think of this version of him. They took the raw ingredients—established in X-Men #1—and refined and amplified them beautifully into the genius, joyful, gymnastic, blue-furred, simian character that everyone fell in love with.

You could argue that his behavior is a compensation for his appearance. He makes the extra effort to be kind and generous to distract from the fact that he looks like he might chew your face off or pick a flea out of his fur and eat it.

I should say that within the current continuity, the Cerebro cradles contain deep archives of all mutant memories. So, this version of him still exists.

Hank was on two teams in the eighties: The Defenders and X-Factor, which would see the return of the original X-Men lineup together. In The New Defenders comic, Hank struggles to form that classic “non-team” into a regular team like The Avengers while being at odds with Valkyrie for leadership of the team. While in X-Factor, he falls back into a subordinate role to his old teammate, Cyclops (Scott “Slim” Summers). Given Hank is one of the top, brilliant minds in the Marvel Universe, what kept him from being seen as a Reed Richards (Mr. Fantastic) or Tony Stark (Iron Man) during this era? Does it have to do with the stigma of his character design and how quarterbacks and not linebackers are seen as team captains in the field? Or does his playfulness and need for everyone to get along keep him from effectively leading?

I remember reading an article about grooming politicians, and it’s generally considered a poor choice to grow a beard, because you appear like someone who has something to hide. That aligns with your quarterback theory. Beast doesn’t look like a good guy; he doesn’t look like a leader. Maybe, as time goes by, the perceptions of others start to rub off on you and pollute your sense of self and inhibit your potential.

In the nineties, there is a paradox of Hank becoming a guide from the side to allow the comic books to focus on fresh new characters. However, to non-comic book readers he was a face of the X-Men and the first mutant in The Amazing Spider-Man daily newspaper strip. The X-Men: The Animated Series began with Hank in prison and on trial in the media for being a mutant. In the comics, Dr. McCoy was sequestered in the lab trying to cure the Legacy Virus. This era also saw Hank more reserved and bookish, wearing glasses, and quoting philosophers. Hank takes on the role of the public face of mutant kind but does speaking for all mutants affect Hank speaking just for himself?

You’re talking about the comics in chronological terms. That’s interesting to me, because I have no understanding at all of Marvel or DC continuity. That’s because of how I grew up. I moved around constantly as a kid. I didn’t have a comic shop that served as my home base. Instead, most of my comics were erratically purchased from the spinner racks in gas stations and grocery stores or from bins at garage sales and flea markets. Even if I did find a comic shop, I was probably randomly buying back issues, because they were cheaper. I have no idea, as a result, what was published when, because I’d be reading a seventies issue one minute and a nineties issue the next.

So when you say, this is how Beast or Punisher or Spider-Man—or whoever—changed over time, you know more than me. I have a more holistic understanding of characters.

With that said, I religiously watched X-Men: The Animated Series when I was a kid, so that version of McCoy—and his frenemy relationship with Wolverine—probably imprinted itself on me as much as any of the comics. Beast as the statesman and strategist. You certainly see that in my writing of him.

Hank has another mutation in the aughts into his cat-like look. This period also had writers like Grant Morrison in New X-Men (2001), Joss Whedon in Astonishing X-Men (2004), and Ed Brubaker in Secret Avengers (2010) putting Beast front and center. Instead of reverting his demeanor on these teams back to the “beautiful, bouncing Beast” for fans from the seventies and eighties, how do writers respect the creative changes Hank has undergone to present a whole new Beast in both look and personality?

The Morrison and Quietly run is one of my favorites (as some might guess, since I’ve given Kid Omega a lot of real estate in my run on X-Force). The weirdness and darkness are really appealing to me. And the feline appearance of Beast was a fun evolution.

We haven’t talked about Hank McCoy and Professor Charles Xavier yet. How much is Hank, as an adult, a proxy/placeholder for the vision of Professor X in a group like the Illuminati or to other mutants when teaching at The Xavier Institute? Does the shadow of Charles Xavier dictate the history of Hank’s behavior? Should readers not be as surprised when Hank goes on his own to make major changes to the timestream in Brian Michael Bendis’ All-New X-Men (2012) or his recent actions with Krakoa when Beast is looked at through the long lens of having Professor X as a mentor?

I’ve kept Charles mostly off stage for this exact reason.

Every title—and there are a lot of X titles—have their core characters. Sure, Logan can show up in another book, but it’s in the Wolverine mainline where the important stuff is going to happen.

What you’re talking about—with Charles—is pretty significant, and he’s not one of my characters. He belongs more to X-Men or Immortal X-Men. So Gerry Duggan and Kieron Gillen will determine his fate (and his faults).

Krakoa is the mutant nation, and X-Force is its CIA. That was my pitch for the book. Charles gave Beast carte blanche when appointing him as the Director of Intelligence. Hank didn’t have to report to the Quiet Council or get approval for their dark deeds. Did Charles shut off his psychic connection to Hank? Was he unaware of what was going on? We’ll see in the pages of X-Men or Immortal X-Men but not in X-Force.

Every powerful country in the history of the world has killed people and engaged in unsavory, amoral activity that doesn’t square with patriotism and the public-facing view of a nation. At the very least, Charles knows this in the abstract—but perhaps not in the specifics, re: the shadow ops of Beast’s X-Force.

In X-Force 40, we read that Hank has been manipulating the time stream to ensure his plans see their completion, which shows his dimensional chessboard way of thinking. What can you tell us about Hank’s plans and The Ghost Calendars storyline? How has Hank standing against multiple world conquerors over the years shown he’s learned from their mistakes but is also in a place to do what he feels needs to be done, regardless of what others think of him in the vein of a traditional Marvel villain?

Keep in mind that Beast has a utilitarian code. He wants the greatest good for the greatest number of mutants, no matter the cost. That might lead him to assassination, blackmail, timeline manipulation, and genocide. He’ll even kill his own. We’ve seen him murder Wolverine and resurrect a more mindless version of him to serve as a more willing soldier of Krakoa. He’s ruthless. But there is a code. He operates with the cold indifference of a surgeon. Think of him as a Kissinger figure.

He hasn’t become this way out of nowhere. He’s made many decisions over the years that were troublesome. Look at the Legacy Virus, Threnody, and Mutant Growth Hormone. Look at his involvement with the Inhumans and Illuminati. But his current position of power—and the longtime victimization of mutants—have festered and encouraged these darker corners of his mind.

Where can our readers find you online and find more about your other work?

I’m on all the obnoxious social media platforms. I also have a website that I don’t do a very good job of updating: www.benjaminpercy.com . We’ve been talking about comics, but I’m also a novelist, and my newest book—The Sky Vault—releases this September.