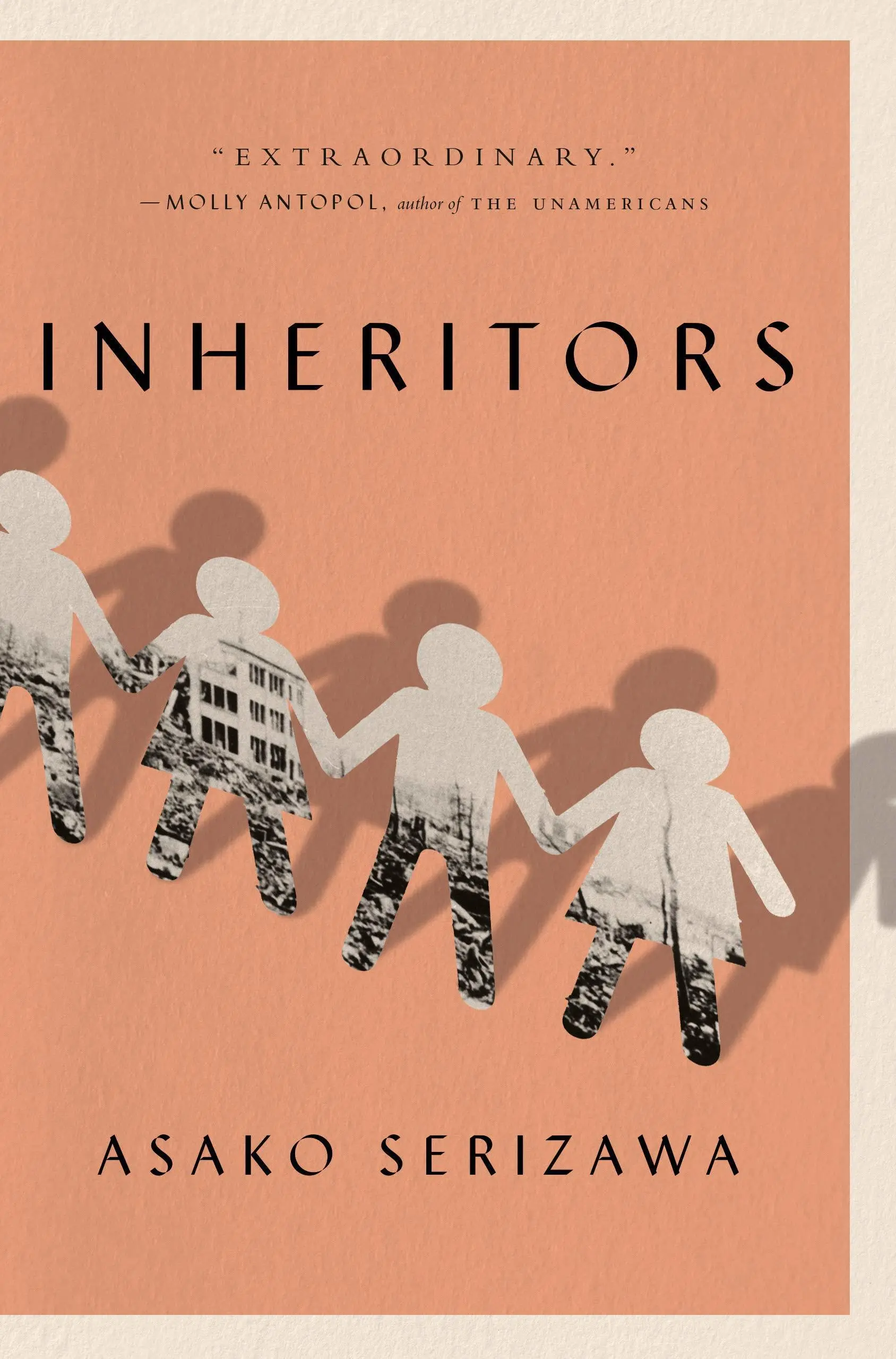

An Interview with Asako Serizawa

Words By Asako Serizawa, Interviewed by Asma Al-Masyabi

Form performs a large role in how the stories in Inheritors are told and the deeper themes of your collection. Why did you feel it was important to tell certain stories in form?

Form determines the shape of a story, the way a photograph frames what’s included in/excluded from the visual field; it determines how we understand the story, what it’s telling us about a history, a culture, a people, an event. Also, Inheritors includes a range of underrepresented/marginalized perspectives challenging official and popular nationalist narratives of World War II’s Asia-Pacific side, twinning the question of form and responsibility in other ways.

The main character in “I Stand Accused, I, Jesus of the Ruins,” is a World War II war orphan, a figure routinely subject to roundups in postwar Japan and often depicted as an abject stereotype (dirty, homeless, criminal). The story is written in part as a series of police witness statements because that’s where one might find more traces of his life—a fact integral to his story.

“Willow Run” is similar. For complex reasons, the interviewee’s story is rarely told, except from the male perspective. Among the only places I could imagine her story surfacing in her voice and perspective was in testimonies. To comment on this and on the complex interplay of power that undergirds the construction of testimonies, “Willow Run” is told through one side of a recorded interview.

What and whose story I wanted to tell determined the form, the “how.”

Many of the stories in Inheritors contain an element of mystery. How did you find a balance between telling the reader information, having them figure it out themselves, and withholding it?

Balance—or, more accurately, information management—is such a tricky element. My intention is never to be coy, obscure, or otherwise withholding, but I’m committed to writing fiction that invites readers’ active participation by balancing critical engagement and emotional resonance.

Since Inheritors is historical fiction and based on real events, research must have played a large in the shaping of the book. What did this research look like for you?

Like most fiction writers engaged with history, I spent a lot of time with primary sources. But documents related to war are often unreliable, incomplete, and/or unavailable because they were destroyed or otherwise suppressed, repressed, or shaped, or they were inaccessible to me because they are classified or in archives scattered around the globe.

For these reasons, I spent more time looking at scholarly material around each subject and topic to understand the general field, its issues and fault lines, and its unresolved points of contention. I also researched cultural output to see how the subject and/or topic had been approached and how I wanted to respond or intervene and why.

Many of the topics explored in Inheritors can be considered rather heavy. How did you take care of yourself while writing difficult scenes or topics?

Taking real breaks from the project was essential, alongside maintaining daily physical activity to move the energy, mental and emotional. Most vital was keeping perspective and remembering the larger goal: why I’m engaging with the material and writing these stories in the first place.

Your stories seem to center the human perspective of historical events. Can you tell me a little more about this focus?

In a time of accelerated media consumption and dissemination, active conflict and polarization, when we most need to remember the human costs, it’s alarming how quickly human realities, stripped of nuance and complexity, are transformed into statistics, a news brief, a trope replete with stereotypes. At the same time, human experience is shaped by the individual’s social, cultural, and historical context. And when we focus only on the human experience, our understanding of the context is dangerously prone to fade out of view. I try to keep both in focus and integrated, their complexities squarely centered.

How would you describe the publication process of Inheritors in three words? What didn’t you expect about working on its publication?

Intense, scrambling, and rewarding. I generally try not to have expectations, and when it comes to publication, every book acquires its own twisting trajectory, contingent on myriad unforeseeable factors.

Still, the spiking fear around releasing a book into a fraught world full of unpredictable readers was a surprise. And, of course, no one launching a book in 2020 expected the pandemic.

You’ve described yourself as a slow writer and mentioned Inheritors took you almost thirteen years to write. What does being a slow writer mean to you?

Writing, for me, is 85 percent psychological. Working through doubts, fears, hopes, my sense of responsibility as a writer, and the muddy question of desire versus creative necessity, takes time. As does the reading and rewriting necessary to translate vision into written form. Sometimes, drafts stall because we lack the understanding that can only come from lived experience. Accepting my own process, understanding its merits, and trusting the accretion have been pivotal. A paragraph could take days, a story a year or more, but the work is better for it.

You’ve mentioned that you have a novel in progress! What differences are there between working on a short story collection and crafting a novel?

Each story in Inheritors required a discrete body of research, and for each I ended up doing enough research to write a novel, which had to be distilled and faceted to fit the mosaic of the collection. The novel I’m working on also traverses time and geography, but there are far fewer perspectives, and the research has been less unruly and branching. The canvas of the novel feels vast, but the project itself feels oddly more manageable, though I have to unlearn the impulse to distill—or, perhaps more accurately, learn how to allow.