An Interview with Alix E. Harrow

Words By Alix E. Harrow, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

Just in case the person reading this is unfortunate enough to not know anything about you, can you tell us a little bit about how you got into writing?

I am a full-time writer living in Kentucky. I got started writing after grad school when I was having a lot of feelings about the kinds of books that I used to love. I was trying to find ways to regain that sense of wonder but reduce some of the problematic things that I now realize as an adult.

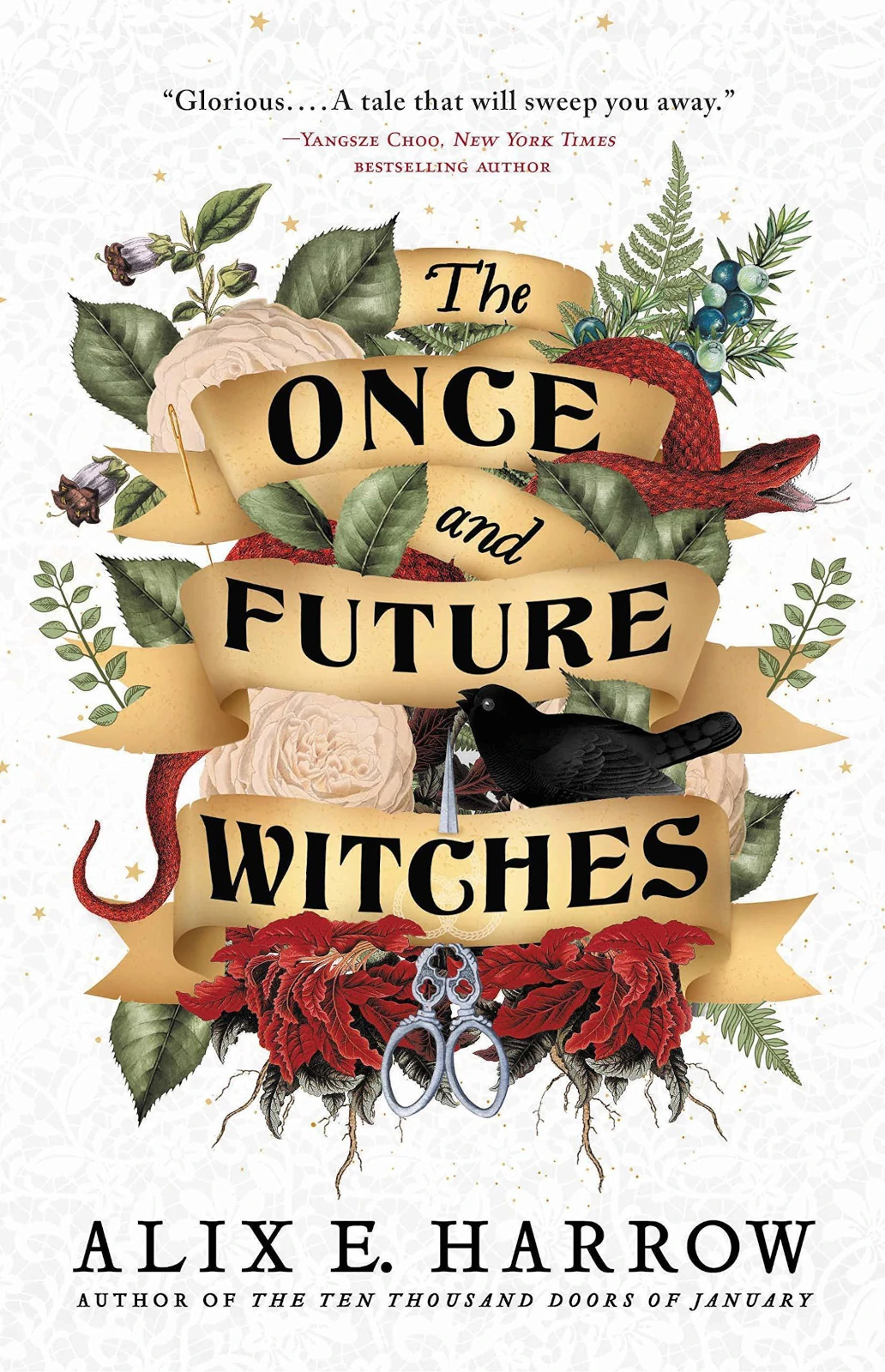

I love that. So of course, The Once and Future Witches is your second book. What other writing have you done before that? What was the trajectory?

I knew I wanted to write novels because that’s mostly what I read, but I very arrogantly thought I’ll just start with short stories. Short fiction would be like training wheels, right? It’s not. It’s totally different. But it did afford me the opportunity to practice basic craft-level stuff. So I wrote some short stories, I submitted them, I got rejected a few times, and then, through writing short fiction was actually how I got my first book deal. I sold a story about witch librarians and it went around the internet a little bit. Then I got a DM from an agent and an editor who said hey, you don’t have a novel, do you? And I said give me a week and I’ll be back to you! So I finished revising Ten Thousand Doors of January and sent it to both of them and that led to both of these books.

Where did the inspiration for The Once and Future Witches come from?

I wish I had a story about how it came to me in a dream, or, I don’t know, the spirit of being a woman spoke to me, but I stole the idea from my husband. The witch librarian story did well early on, and Asher said that I should do witch everything: witch garbage collectors, witch activists, like the women’s movement. So when Orbit, the publisher, asked if I had any ideas for a second novel, I thought, suffragettes, but witches. That’s as much as I knew about the book at that time.

At the core, we have Suffragettes and witches. But we also have this very intense and acrimonious sisterhood. Did you pull that from your own life? Tell me the backstory.

Actually, in the first draft, they weren’t sisters. They were just two women with very different life experiences and their ages ranged a lot more. I got maybe 20,000 words in and then realized that it wasn’t working. I realized that other authors are better at creating immediate emotional relationships between characters who are strangers at the beginning, and I just was not pulling that off. I wanted the characters to have some weight between them already. So when I rewrote it, I realized that they need to be sisters. This worked on a thematic level, too: if you’re talking about sisterhood on a large scale, it worked better to also be talking about literal sisterhood. After I wrote the first draft, I also wondered if that had anything to do with the fact that I was, as an adult, rediscovering my relationship with my younger brothers.

One of the things that I really love is this weight these sisters carry between them. What was it like trying to create these heavy backstories and then slowly unravel them to the reader?

One of the questions that I really grappled with in writing this was how dark I wanted it to be. In the early draft, I kept flip-flopping between whether it was a light, magical romp, like Jonathan Strange, where it’s a period piece with magic, or if this was a true exploration of women’s history and the Suffrage movement, which is extremely bleak. I wanted to find ways to acknowledge the heaviness and trauma without reveling in it on the page, so it was important to me that most of the worst things that have happened to these people have happened in their past. This was more of a grappling and healing than a descending-into-darkness narrative.

Early on, Juniper talks about the idea that a woman’s right to vote and magic are essentially the same discussion. Talk to me about how that came together, from stealing your husband’s idea and then making it so poignant.

Yeah, I mean, that’s why I stole his idea. One of the things that makes me like fantasy so much is that you can take invisible stuff and make it be visible through the use of the supernatural or the magical. Women’s power is generally not something you see or feel—the right to vote is in many ways a theoretical and distant thing, so translating that into literal power kind of feels obvious. It’s using the magic to literalize the sense of women’s power.

Another thing that I really love about all your writing, actually, is just this focus on how important names and titles and labeling is. I love how the sisters’ names fluctuate between how they grew up and how they talk to each other, and how that relates to their father. Where does that sort of power come from, and how do you come up with these enchanting names?

I’m just a sucker for alliteration. And, as I looked historically, many witches had alliterative names. It’s part of their connection to folklore. It’s not an original thing in fantasy—it’s a trope. To name something is to know it and to understand it. And I do understand that that’s a very Western lens of knowledge.

Other than theoretically, I also find it to be true of my own name. I have a girl named Alex after her father like James is named after her father in the book, and my family calls me one thing and my friends call me another and I have a publishing name. I just think that names really are a good shorthand for identity in a way.

One of the other things I found striking about all of your writing is how rich the language is. It’s the little bits of alliteration, it’s the fact that so many things are connected to the senses. What was it like to develop your voice, and how did it shift between these two novels?

I think that’s one of the coolest things about starting in short fiction. It lets you play with voice a lot. If you sit down and start with a novel, you have to maintain a consistent voice for 100,000 words. Doing short fiction, you can fit your voice to the project, so that was a really fun way to explore. It was actually really hard for me to find the right vibe for this book. Ten Thousand Doors was easy, because in some ways, it was talking really specifically to late Victorian children’s literature, and I knew that the main character’s voice would in some ways mimic those styles. But it took me a while to figure out what The Once and Future Witches was speaking to. It was in the third person instead of first, it was in the present tense instead of past, and it didn’t have an obvious antecedent to me. Until, in the second draft, I figured out that they were going to be retold fairy tales and that the entire thing would be in some ways told like a fairy tale, and so I tried to use more repetitive phrasing the way folklore does and more alliteration and make the figures more distant from you and silhouetted because that’s how I feel like older stories and fairy tales work.

Speaking of older stories and fairy tales, of course, we get interjections of these old folklore pieces throughout. What was it like to do the research on that, and how did you decide what you should borrow, what becomes your own, and how did that whole facet of the book come together?

Slowly. I didn’t have those in the early draft at all. I was trying to jam way too much world-building into the text in a way that felt really forced and terrible. I just felt like stories are how you learn a culture. To me, they’re the most revelatory thing, how we tell stories, and what stories are popular and remembered. I was thinking about how to explain what the perception of witches is and the role of women in this universe. And then I thought, well, I’ll just take familiar stories, things that everybody knows, and show how they would be told in this world. I decided to do this by dragging the witches out of the margins and putting them in the center of the fairy tales. And it was really, really fun.

I didn’t have to do that much research for the more familiar Grimm’s fairy tales, Western ones. Most of the research I did, later there’s a few that are, one that is based loosely on African-American Antebellum folklore, like world traditions, and then there’s one old one from Russian folklore. Those took a lot more research.

I remember very early on when we were talking about Ten Thousand Doors of January, you told me that after you had already moved forward with your agent, she sat down and said that the book was called Ten Thousand Doors but you had very few doors. She said to go back in there and give her more. Was there an equivalent with this book, where you realized, actually, I’m missing this big part of the story?

I actually had to go back way more this time. I really struggled to write this book for a bunch of reasons, one of which was the sort of second-book syndrome thing. Another which is just living in a post-2016 world, I have a two-year-old, and my second kid was born right as I was starting the draft—it was just really hard. It took a while and I kind of struggled through a draft and finished it on time.

I sent the draft to my editor, and she sent back a twelve-page, single-spaced edit letter, which was very intense. Basically, the problem was that there needed to be more everything. I had the same amount of plot, pretty much, and the same characters jammed into about 40-50 thousand fewer words. It didn’t feel great. And in my head, I was adhering very strictly to a word count in my head. I followed my outline, and I should have known that it wasn’t working.

Nothing had a chance to breathe, and there weren’t huge emotional payoffs. I think my editor’s letter said it felt like a mattress shoved into a pillowcase. So the rewrite of this book was pretty much adding more everything—more magic, more emotional connections, more relationships, the rewritten fairy tales. It was awful, because I had to rewrite the entire book in two months, but it was also satisfying work because I was finally making it right. If I just turn off my word counter, it’s way better, because it’s more fun!

What was the first word count you aimed to get when you turned in that draft?

I think I was aiming for 100 thousand and I hit like 110 thousand.

Wow. That’s a tight word count for your genre.

Yeah. Well, they did want it to be lower because they’re sort of aiming for that literary sci-fi. Literary people don’t generally pick up the 500-something page book.

What’s up next for you, a woman who has now achieved her second book?

I’m working on another book, but I can’t really talk about it. The next thing to be published is a Tor.com novella, actually, that was really, really fun. It was the most wonderful thing to write after the second book was just really hard. I got this contract to write what I pitched as Spider-Versing a fairy tale—have you ever seen Spiderman: Into the Spider-Verse? So I get to do a Sleeping Beauty retelling where all the Sleeping Beauties crash through the multiverse and claw each other out of their story. It was so fun.

Not to make you talk about the next book, but is the idea your husband’s?

No, it’s not! The next book came out of a John Prine song, actually. The “Paradise” song, “Take Me Back to Muhlenberg County.”

If you could only say one thing with this book, and that could judge whether or not it was successful, what do you hope that any reader takes out of this?

I hope that you end this book curious but also hopeful.