An Interview with Ainslie Hogarth

Words By Ainslie Hogarth, Interviewed by Ciena Valenzuela-Peterson

As the author of four novels, how has your approach to writing fiction evolved since your debut? Is there anything you know now—about writing, publishing, or life—you wish you could tell your younger self?

My writing approach hasn’t changed too much—I’m always trying to write something original, something that isn’t just more noise. A piece of practical advice that I wish I knew myself back when I first started is that it’s better to have no agent than the wrong agent.

As a horror fan, I’d love to hear your thoughts on the genre; why do you gravitate to writing horror? When is horror the right choice for a story or a message? And what role does social commentary play in your approach to writing a horror novel?

I suspect the reason I gravitate towards writing horror is simply that I love reading it. It’s a genre that lends itself particularly well to social commentary because of how flexible you can be with reality—it’s easier to make a message hit harder when you have that much play in the story’s world.

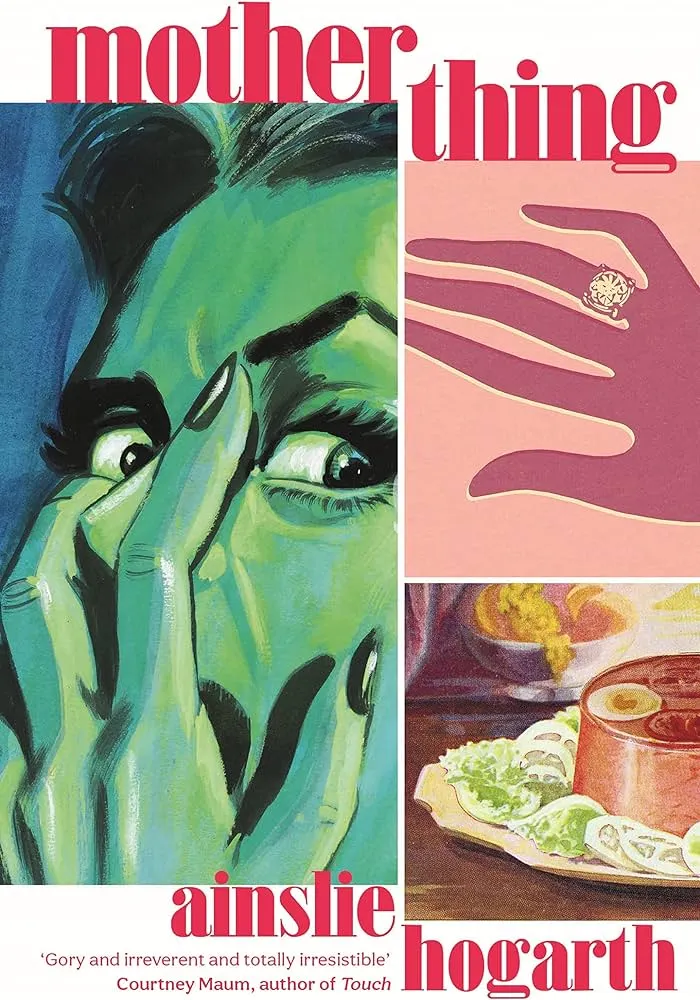

Your most recent books, Normal Women and Motherthing, seem to draw on 1950s aesthetics in both cover design and domestic themes. What inspires you about the 1950s? What does the 1950s lens reveal about our modern era?

The 1950s was the dawn of the advertising boom. Ideas about gender and society were suddenly defined by what could be sold to people, and products became a kind of language to describe complex biological/cultural/socioeconomic narratives. We tend to look at that era as a curiosity, as something far removed from our lives today, but those capitalist prototypes are more like our early ancestors—we live every day with the traces of their vestigial roots.

Much of Motherthing hinges on the role of food in social relationships, from the recipe book promising to “save your family” to the coworkers at the communal fridge. What fascinates you about food? How does it fit into contemporary society, particularly with regards to women? And have you ever really tried jellied salmon?

I haven’t tried jellied salmon! But I certainly would. Honestly, I just love food. I love eating. I’m very fascinated by people’s relationships to food, how food is branded and marketed, and all the ways we can read food now—a person’s cupboards can really tell us something about them, or so we think. Before, all a person’s cupboard told us was that they had a human body.

A common theme in your work is keeping up appearances—not just in terms of physical beauty, but female characters hiding their distress from their husbands and the world around them. What is the appeal of writing these kinds of characters?

I just think that that’s what a lot of women do. I’m a mega fan of the Real Housewives franchises, and each series inevitably becomes a kind of endurance test for who can make their life seem the most enviable for the longest stretch of time—essentially, who can hide their distress most convincingly. Eventually the bell tolls for them all, of course—but oh man, what a ride.

In Normal Women, on face value “The Temple” yoga studio feels like spot-on satire of contemporary mommy culture. Where did the inspiration for “The Temple” come from?

I drew inspiration for The Temple from a few different places—the connection between sexual and spiritual healing has a long, well-recorded history—but in particular, Gwyneth Paltrow’s lifestyle brand GOOP’s white-and-wealthy coded umbrella of wellness really focused it for me. With “The Temple,” I wanted to explore wellness and all the slippery ways people, even well-intentioned people, use the term for themselves.

One of my favorite things about your work is your fearlessness in satirizing the good, the bad, and the ugly about womanhood and femininity, bringing us wonderfully complex and neurotic characters like Abby and Dani. How do you approach writing about womanhood, femininity, and motherhood? In your opinion, what constitutes “good representation” for women in fiction? How do you grapple with that question when writing “dark fiction”?

This is a great question. As a woman writer, it’s hard to get around this idea that you have to be SAYING SOMETHING—in that grand, all-caps way. Good representation, to me, is when a character or a story subverts that expectation, when a character feels truly real enough that they transcend any message. I had a bad review once where someone said my book was so feminist that it circled back into misogyny, and I felt very proud of that!

What is the biggest takeaway you hope readers have after reading Normal Women?

What I really, really hope is readers come away thinking about the divisions of labor in their own relationships. Normal Women is a kind of speculative origin story about women in heteronormative relationships coming to be paid for the labor they’re already doing for free—caretaking labor, emotional labor, sexual labor—but it’s also a study of the uncomfortable hypocrisies inherent in commodifying any service or resource. It’s a challenging book, which demands self-reflection, so I’m not surprised it has been polarizing, but I hope that even people who didn’t like it were still able to take something away from it.

Do you have any advice for all the aspiring writers out there?

Keep at it, despite the rejections and disappointments. That’s all you can do. I’d been at this for almost ten years before Motherthing hit. There aren’t a lot of ways an artist should model themselves after Kanye West, but cultivating a near-psychotic confidence in your own talent is definitely one of them.

What’s next for you?

Next up I’m working on another book that, like Motherthing and Normal Women, doesn’t really fit into any specific genre. My agent pitched it as Notes on an Execution meets Creature from the Black Lagoon!