A Study in Classics: Three Lessons You can Learn from Dracula

Words By Maribel Leddy, Art By Modern Library

Why and when does suspense work in fiction? It’s a question I ask myself a lot—if a story or novel doesn’t have suspense where it should, the reader loses interest. But it can be difficult to determine the line between saying too much and not enough. What information do you keep a mystery for the sake of suspense and when do you reveal important details to hold the reader’s attention? Sometimes the best place to find answers to these age-old questions is in books that are as time-tested as Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

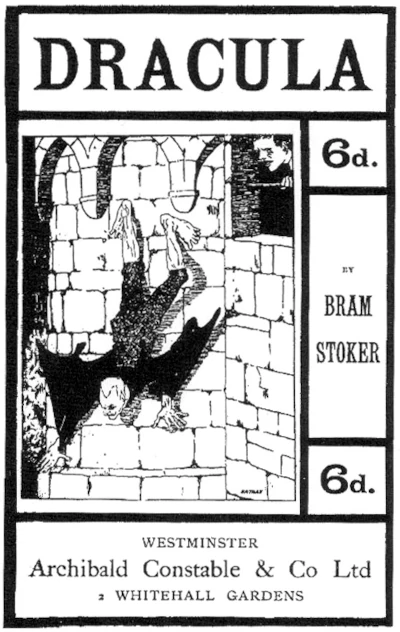

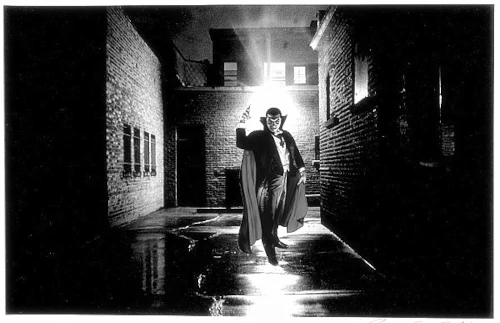

Dracula is one of those novels that everyone knows but few have actually read. Count Dracula himself, of course, has made his mark on popular culture and media, but the protagonists of the novel, with the exception of Van Helsing, have been largely forgotten.

Reading Dracula in a contemporary setting is kind of hilarious. Why? Because knowing what you know about the mysterious figure at its center beforehand makes you scream at the main characters as you read. Seriously, Jonathan Harker, the guy has fangs. He doesn’t try to hide them. Please leave his castle and save yourself.

Even if I pretend that I don’t have preconceptions about Dracula, I still find myself laughing at moments such as the one where the Count flings a mirror out of a window and cries: “And this is the wretched thing that has done the mischief!” Dracula, my guy, I know it must be difficult to maintain that hideous mustache if you can’t see your own reflection, but tone down the saltiness, please! (Or, in this case, would it be garliciness?) Despite this, I keep turning the pages because Stoker has imbued a sense of mystery and suspense into every word of the novel. But how does he do it? And what lessons can a contemporary writer take away from this classic?

Lesson No. 1: In suspense, perspective is everything.

Like many early novels—Austen’s Lady Susan or Richardson’s Pamela, for example—Dracula is written in the epistolary style, with all points of view offered in the form of first person diary entries and letters. The first four chapters come from English solicitor Jonathan Harker’s as he travels to Transylvania to meet his boss’ client, Count Dracula.

I admire Stoker’s dedication to the epistolary form, if not the form itself, because the overall effect is that the narrative is both retrospective and ever-growing. Contemporary horror has, for the most part, left this antiquated style behind, but certain modern adaptations still exist: think of films like The Blair Witch Project, which utilizes a similar effect to keep viewers on the edge of their seats. Knowing that the characters are alive as they write in their journals or respond to letters, but not knowing how long they’ll stay that way keeps the mystery moving and increases the fear factor.

Jon, after being warned by no less than an entire village of people not to go to Dracula’s castle (and not in a subtle way, either, but in a “here’s a crucifix, I’ll pray for your soul” kind of way), arrives and meets the Count. As time goes on, he realizes that he’s imprisoned in the castle and must try to escape if he wants to live. After a fun series of events in which Jon watches Dracula turn into a lizard and eat children, he ends these four chapters on a cheery note: “Goodbye, all! Mina!” before he attempts to escape.

This leads us to…

Lesson No. 2: Let cliffhangers be cliffhangers—but don’t leave them hanging at the end!

The next chapters pick up with a series of letters between Mina Murray, Jon’s fiancée back in England, and her best friend Lucy Westenra. Also introduced are Lucy’s three suitors: Dr. John Seward, Quincey Morris, and Arthur Holmwood, who play roles both in saving Lucy and adding to the metaphorical weight of the novel. For example, Dr. Seward, the director of an insane asylum, has a patient whose fascination with consumption parallels major themes of the novel.

There is more than one cliffhanger in Dracula. At the end of chapter XI, we read Lucy’s parting words after she recollects the events of a terrifying night: “Goodbye, dear Arthur, if I should not survive this night. God keep you dear, and God help me!” This time, Stoker subverts the trope he used in Jon’s situation by resolving the cliffhanger in the next chapter.

But Stoker uses both cliffhangers to keep the reader ravenous for the next bite of the mystery. By taking us to England without knowing what happens to Jon, he’s saying: pay attention, Transylvania and England will eventually overlap. By switching perspectives from Lucy to Dr. Seward following Lucy’s brush with death, he’s saying: pay attention, she avoided death so that something worse can happen to her!

Stoker uses these cliffhangers like threads, weaving them throughout the plot and making sure they connect with each other and the overarching mystery. The ultimate effect is a deep sense of foreboding suspense that is only lifted in the final moments of the novel.

Lesson No. 3: Building an atmosphere is the key ingredient to creating suspense.

If you want to understand why Dracula‘s suspense is so successful, read the first page of the novel. As Jon begins his journey, Stoker introduces three important and lasting themes: waiting, fear, and thirst.

In the very first sentence, Jon’s train to Vienna arrives late, forcing him to wait an hour. He writes, “I waited with a sick feeling of suspense,” and suddenly the reader, too, is on edge with ill anticipation as they wait for the events of the novel to unfold.

Not long after this, in the very first paragraph, Jon introduces fear to the text: “I feared to go very far from the station.” From then on, both Jon and the reader are alert to other frightful happenings, and the closer we get to the castle, the more times the word “fear” appears on the page. In this way, Stoker literally increases the sense of fear and suspense imbued in the text.

Jon then writes that the first food he eats on his journey has made him thirsty. So thirsty, in fact, that he mentions it again on the very next page. The reader’s attention is therefore drawn to the large role that food and drink, or consumption, will play throughout the novel. Stoker capitalizes on this as Jon loses himself in the castle and the reader notices that he begins to eat and drink less and less.

The introduction of these three themes on the first page build the atmosphere of the entire novel. From the beginning, even before the actual events of the story, we understand the dark and fearful world in which Dracula is set.

Dracula answers the why and when of how suspense works in fiction. It’s not only a fun read, but an important one. These lessons on writing suspense are three among many that can be found in the novel. Whether it’s as a timeless horror classic, contemporary comedy, or treasure trove of teaching, Stoker’s magnificent work has something to offer every reader.