A Study in Classics: Oscar Wilde and Camp

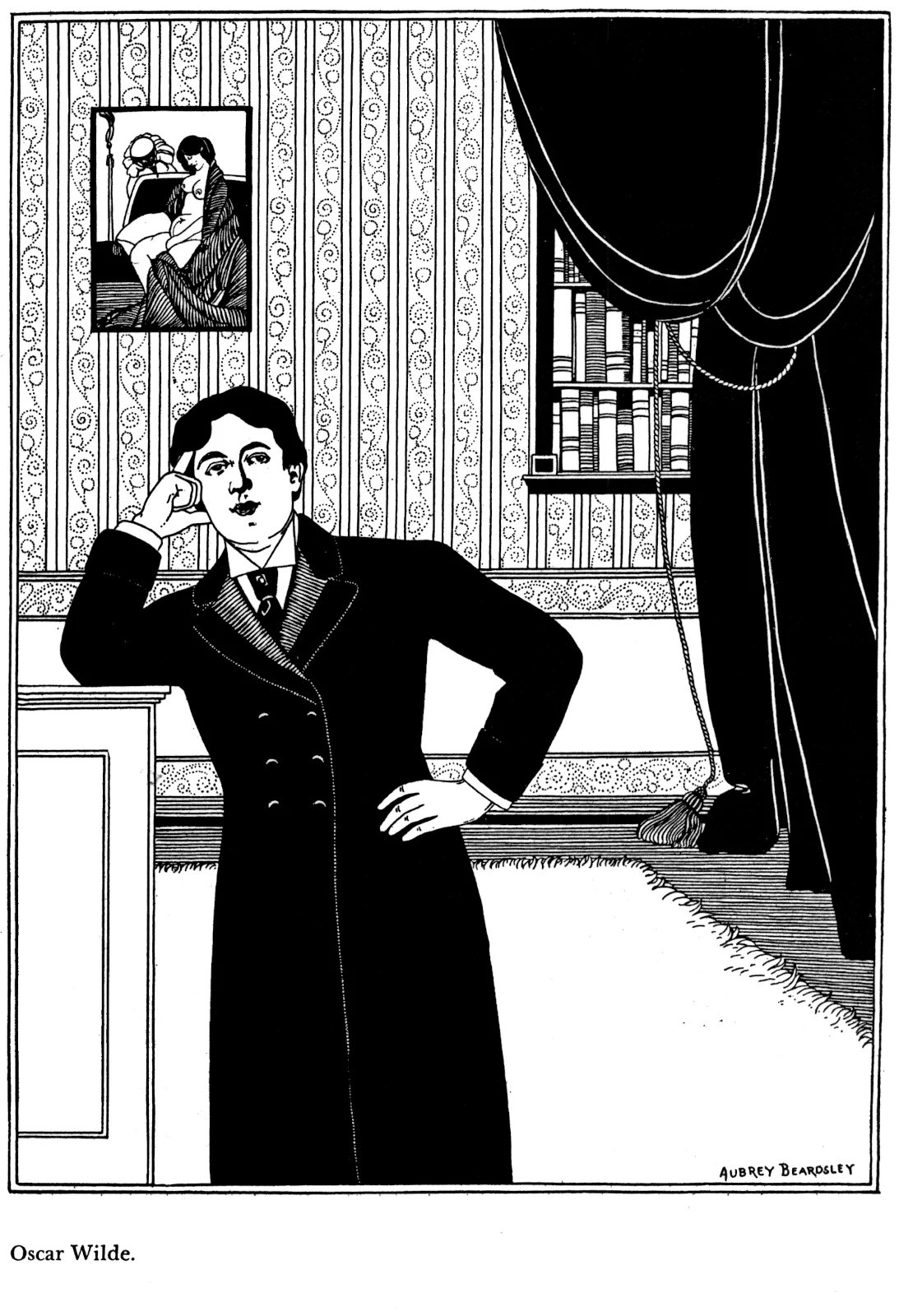

Words By Jerakah Greene, Art By H.S. Nichols

If you had a Twitter in April of 2019, you probably remember this year’s Met Gala, the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual gala to celebrate the year’s newest fashion exhibit, hosted by Vogue editor, Anna Wintour. For weeks, it was all anyone could talk about—the biggest fashion event of the year. As always, it was themed. This year’s was “Notes On Camp.”

Now, if you aren’t a gender studies major, you may have been a tad confused when the theme was revealed. Some Twitter users wondered if the Kardashians would walk the red carpet in camouflage with a grill in tow. But camp, in the Met Gala’s context, was based on Susan Sontag’s essay, “Notes on Camp.”

Camp, stripped down to its bare bones, is an evolved type of aestheticism. Whereas aestheticism values artistic, material, and physical beauty, camp takes it all much, much farther. In fact, Sontag wrote that “the way of Camp, is not in terms of beauty, but in terms of the degree of artifice, of stylization.”

Camp does not simply value the beauty and perfection in things, but the outrageousness of them, the absurdity. Camp is supposed to make you double-take. It’s supposed to make you uncomfortable, aroused, excited, emotional. “Camp,” she wrote, “sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a lamp, but a ‘lamp’; not a woman, but a ‘woman.’ To perceive Camp in objects and persons is to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role. It is the farthest extension, in sensibility, of the metaphor of life as theater.”

It is for these reasons that Susan Sontag dedicated her essay to Oscar Wilde—the King of Camp.

Oscar Wilde was born on October 16, 1854. He came of age at the height of the Victorian era and, while an undergraduate student at Oxford, began to gain some popularity as a poet and scholar. He married in 1884 and, in the years following his marriage and the births of his two children, created a magnificent outpour of prose.

The homoerotic themes in his work were considered immoral, highly contested by Victorian critics and readers—and would play a large part in his imprisonment years later. However, any publicity is good publicity. His next three works—each of them plays, including The Importance of Being Earnest—achieved monumental success. Wilde had solidified himself in the canon of English literature and established a career as a popular playwright.

Around this time, too, he met Lord Alfred Douglass, the man who would become the love of his life. The two were inseparable for four years, before Douglass’s father accused Wilde of homosexuality and Wilde was arrested in 1895. He spent two years in prison, and the last three years of his life in exile. He died on November 30, 1900.

While there is sadness in his story, there is also an everlasting legacy. Oscar Wilde’s literature is painfully clever, sometimes outright hilarious. And, often, it is campy.

In his day, “camp” was aestheticism, which is “the elevation of taste and the pursuit of beauty as chief principles in art and in life.” Oscar Wilde knew, perhaps more than anyone, the importance of appearance. He venerated physical beauty, valued it above everything. To Wilde, art was the most important thing—and the least important. Anything of value had to have artistic beauty—otherwise, what was the point? The preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray explains Wilde’s feelings pretty well:

“Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without being charming. This is a fault. Those who find beautiful meanings in beautiful things are the cultivated. For these there is hope. They are the elect to whom beautiful things mean only beauty.

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

This, of course, makes Oscar Wilde sound extremely shallow. He may have been. But what set Wilde apart from other shallow, conceited, wealthy aristocrats was that his idea of beauty was far from conventional. He was a dandy! He dressed flamboyantly, in outrageous colors and fabrics that made Victorian propriety blush and shudder. Hell—he wrote an entire novel about the corruptive powers of vanity. Dorian Gray’s conventional beauty is, in the end, his downfall.

Nowadays, when we think of camp, we think of drag. Trixie Mattel, one of the most popular drag queens of our age, describes herself as a camp queen, because of her over-the-top makeup looks and outrageous humor. Sontag wrote that camp “is the love of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not.” This applies to drag pretty well, since one of the principle ideas of drag is to turn conventional beauty standards on their head, and to turn the everyday into something absurd. That, in fact, is the entire premise of The Importance of Being Earnest. The plot line is as convoluted as a Shakespeare comedy, but I think this trailer sums it up pretty well.

This video information is available as a Text Transcript with Description of Visuals.

Their costumes! The exaggerated “…fooouuund? In a…handbaaaaag?” This is camp. Wilde’s satirical dialogue lends itself entirely to an over-the-top performance, and audiences have been obsessed for decades.

Camp has evolved since Wilde’s day. When he was gallivanting around England as a dandy, the world thought he was mad. Now, all of the things he loved, the absurdity of Victorian values, bright green suits adorned with carnations, and greatly exaggerated beauty—there is a community that celebrates this kind of outlandish style. Drag is one of the best examples of camp in practice today, and Oscar Wilde would have loved it.

“The hallmark of Camp is the spirit of extravagance,” Sontag wrote. Camp is a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers.” Some attendees simply wore skimpy outfits and doused their hair in oil, calling it camp. Some men wore earrings and were praised for subverting the gender binary. But camp is about the spectacle. Lizzo, in a pink Marc Jacobs cloak with feathers trailing behind her, appeared to be the only one who got it right.