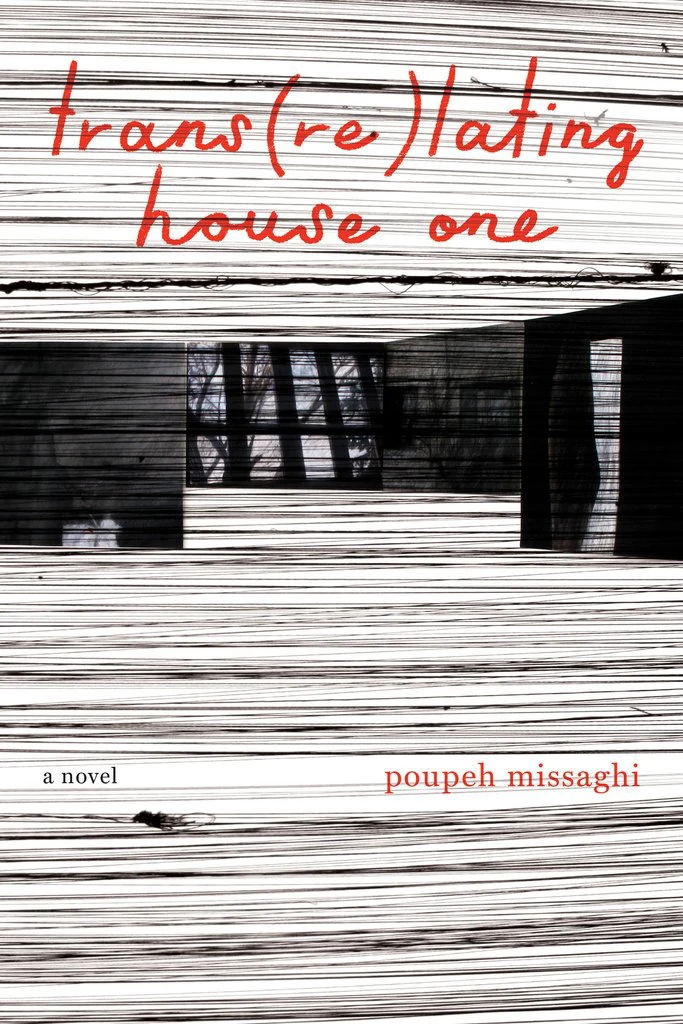

A Review of Trans(re)lating House One by Poupeh Missaghi

Words By Ally Geist

Published February 4, 2020 by Coffee House Press

Trans(re)lating House One is unique in that it is not only a commentary on translating words but also on one’s ability to translate culture and experience. My main takeaway from this novel was that sometimes, it’s not about what we remember—rather, how we remember—that can have a big impact both culturally and personally. This novel is a stunning juxtaposition of different imagery and the collision of Western and Middle Eastern culture and experience. Through Trans(re)lating House One, Poupeh Missaghi seeks to reclaim stories from her culture, to question where those stories come from, and how her culture remembers them.

The novel begins just after the 2009 election in Iran when the book’s unnamed protagonist searches for statues that have disappeared from Tehran. What starts out as a search for tangible objects, though, quickly blurs the lines of reality as it explores the depth of truth and memory. There are two narrative branches that make up the novel: her search for the missing statues and her reflection on memory, grief, and violence. Through different social hubs, in the complex setting of a bustling city, the protagonist asks herself and the reader questions that challenge our understanding of truth, history, stories, and art. The protagonist also questions how our understanding of this history changes with more reflection and retelling, and what the purpose of revisiting art and memory is:

If these deaths have already been researched and documented, why another documentation? If the stories of these bodies have already been told, why tell them again? What is it about translating them anew? (page 97)

By viewing memories as forms of translation, Trans(re)lating House One allows us to think critically about what might be lost in the fog of memory, and how memory might differ from reality. It allows us to consider the stories we may never hear, why they are silenced, and what contributes to cultural and historical erasure. The concept of historical erasure feels especially relevant nowadays, as people have to sift through the noise of media to discover the truth. We see this time and time again with communities of color who have to seek out their stories (apart from the white-washed history lessons in North America), and Indigenous communities who work to reclaim their language, culture, and traditions.

Part of the challenge of reclaiming culture, though, is the lack of a cohesive “translation” from the “norms” that we are taught as a society—this leave us with a lack of words to even describe this loss and reclaiming. When one’s culture is looked at through the lens of another’s, a lot can get lost in translation. This novel works to depict translations across language, culture, and even gender and age. Analyzing these translations made me re-evaluate how I looked at my own bias and judgments. It made me think critically about my own memories, and the histories my culture has entrenched in its memory. It made me want to learn more about the gaps in my education and what I might not know about the history of my own country. This is a jarring but fundamentally important feeling, as cultural change is brought about by questioning the “capital-T” Truth that we grew up understanding, in favor of taking a more culturally relevant approach.

Along this vein, Trans(re)lating House One explores the numerous avenues we can take to come up with a truth or a version of reality. Its underlying philosophy, though, seems to be that we can never capture one concrete image of someone’s story—there will always be something lost in translation. Though this is a difficult concept to wrap one’s head around, Trans(re)lating House One skillfully and thoughtfully guides readers through a self-discovery of sorts.

The title, Trans(re)lating House One is almost a riddle in and of itself. An interesting aspect of the novel’s creation is that it started with Missaghi’s dream journals from 2011 to 2014. According to Missaghi’s interview with World Literature Today, she then put the words from these dream journals into a word cloud generator. Missaghi explains:

The words “house” and “one” come from the word clouds. “One” appears a lot in the dream diary as an indefinite subject, but appearing in the word clouds, I read it also as “house number one,” which reflects both the family house one is born into and one’s homeland, the country that is forever the first home, whose narration is at the heart of my book.

What is refreshing about this novel is that it never attempts to answer questions for the reader; rather, it poses thought-provoking questions that prompt deep self-reflection. This book would be an excellent fit for a book club, as it promotes such insightful conversations. It’s definitely one of my favorite books of the year, and I will be thinking about it for months to come. Coffee House Press has really outdone themselves with this one. If you are looking to curl up with a good book that you won’t be able to put down, Trans(re)lating House One is a great option.