A Review of Solutions and Other Problems by Allie Brosh

Words By Allison V. Craig

Published September 22, 2020 by Gallery Books.

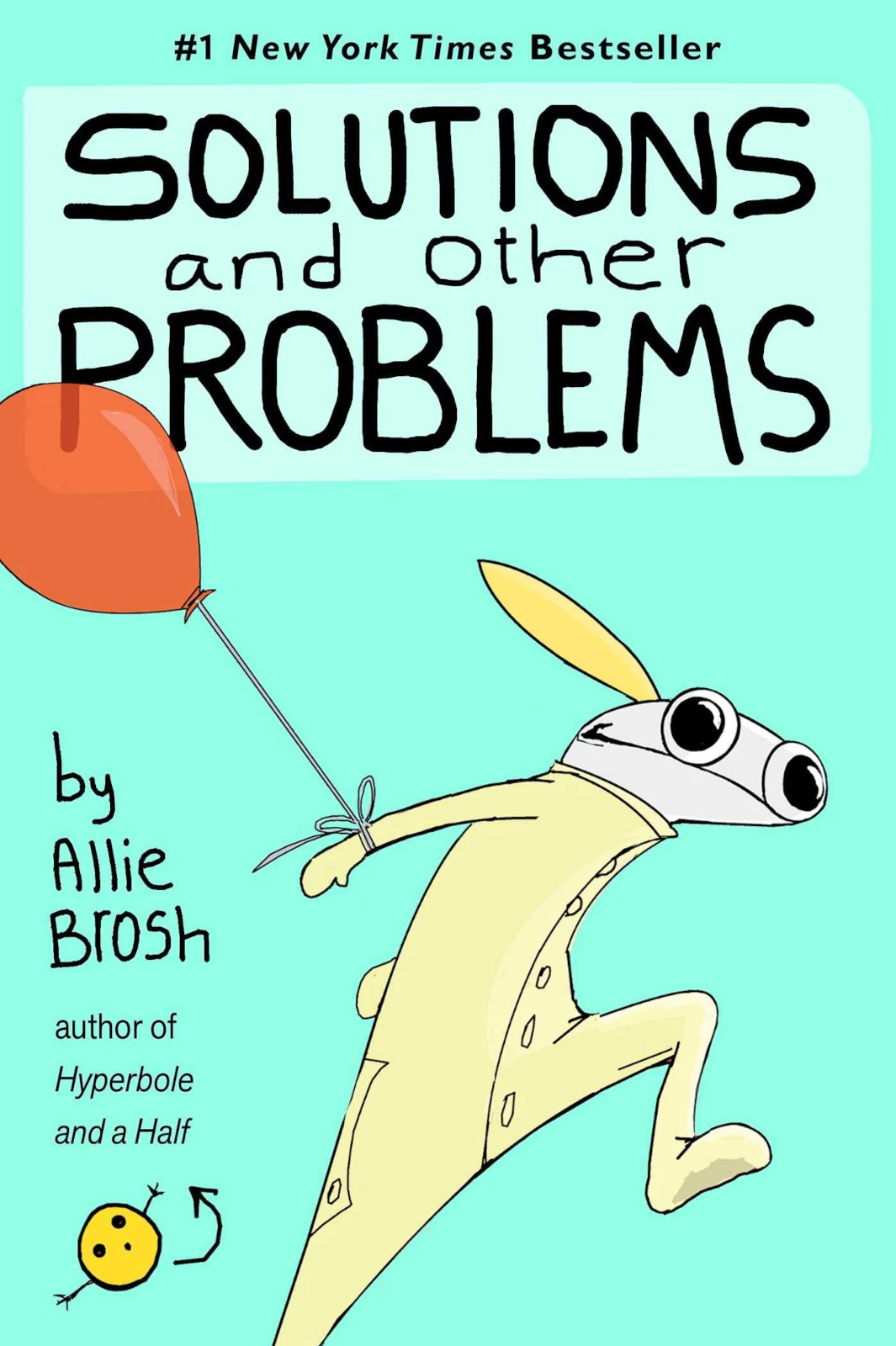

Allie Brosh’s Solutions and Other Problems is the highly anticipated follow-up to the genre-busting, art-blog-turned-New-York-Times-bestseller Hyperbole and a Half (Gallery Books, 2013). Think of it as the narrative-comic equivalent to Alanis Morisette following Jagged Little Pill or Fiona Apple following Tidal. Called “a connoisseur of the human condition” by Kirkus Reviews, Brosh’s autobiographical prose mixed with simple Paintbrush drawings—what Brosh herself has called “stand-up comedy in book form”—is silly, insightful, and poignant. Brosh’s graphic proxy borders on stick figure, with big eyes and a yellow ponytail, and usually wears a vivid pink onesie or, if depressed, a gray hoodie. Indeed, part of Hyperbole’s appeal is Brosh’s candid, humorful, and refreshingly spot-on depictions of her paralyzing anxiety and depression. Solutions and Other Problems is full of Brosh’s trademark whimsy and wisdom and yet is somehow more daring and vulnerable.

I was rereading Solutions while waiting at the doctor’s office purposely ignoring the man who, sitting as close as COVID-possible, kept alternately sighing and commenting about HGTV. I shifted ever-so-slightly in my seat to make eye contact impossible. I didn’t care for the shade of blue they chose for the renovation either but knew better than to say so aloud. I had, after all, just finished Chapter 3, the one about Neighbor Kid, who “gets up at 5 in the morning and hangs out directly in front of [Brosh’s] door like a bridge troll—all who wish to pass must answer her riddles, and the only riddle she knows is Do you want to see my room?” Neighbor Kid does this for “7 consecutive months.” “I have never met anybody,” Brosh writes, “who is this determined about anything.” Anybody, that is, except for Brosh herself. For 7 consecutive months, Brosh avoids, refuses, and outright lies to Neighbor Kid so as not to see her room, no matter how many lamps are in there.

Brosh’s work isn’t just for introverts. However, she makes those of us who’d rather not engage in small talk and have resultantly developed a hard exterior as a coping mechanism, feel a little less alone in the world, and, if I’m honest, a little less guilty. Brosh knows that engaging with others leads to more engaging with others, which is the thing she’s trying to avoid in the first place. Sometimes it’s okay not to engage, even, or maybe especially, in the face of a “5-year-old social juggernaut”: “I mean, what’s going to happen? I go look at her room and then she leaves me alone forever?”

To be fair, Solutions and Other Problems is its own kind of unstoppable force, an unconventional, often nonsensical battle wherein cartoon drawings battle real and imagined fears. I’ll admit that, at first, even though I knew it unfair to immediately start comparing the two, I thought Solutions wasn’t matching up to the brilliance of the sidesplitting Hyperbole. The pacing is different, the tone more somber. Despite both being deeply personal and true about life in ways that only Brosh could illustrate, Solutions isn’t a simple sequel. In one of Hyperbole’s most memorable moments, Brosh compares depression to her fish dying, while her friends keep offering useless advice, like “why not just make them alive again,” or meaningless platitudes, like “fish are always deadest before the dawn.” “Let’s keep looking,” one drawing says, “I’m sure they’ll turn up somewhere.” “No, see,” Brosh’s proxy retorts, “that’s a solution for a different problem than the one I have.” We might, then, reasonably expect Solutions and Other Problems to show us the solutions to the problems Brosh does have. And yet, although Brosh may have created her own rules for Hyperbole, she doesn’t stick to those rules in Solutions.

Maybe Brosh “can’t be contained by the rules” because the rules never made sense in the first place. Heck, Solutions doesn’t even have a Chapter 4, “because sometimes things don’t go like they should.” But that statement turns out to have more significance than a mere explanation as to why she skips Chapter 4.

Brosh’s signature art and philosophical narrative have an effect that’s difficult to capture. The combination of oddly appealing drawings interrupting unique but nevertheless strangely relevant experiences is also profound in ways few authors can achieve. If I were to describe Neighbor Kid, for example, I could say she resembles a skeleton with too many teeth and a lot of brown hair and is wearing a purple t-shirt with a heart on it. While that’s not remotely adequate, it’s not entirely off. How do Brosh devotees explain the hilarity of random “fun facts” during the “serious parts”? Fun facts like, “the Orcish word for hospital is ‘GOREHOSPITSTROON,’ meaning place of one thousand tubes and no answers” or “in a world where fruit was money, it would cost too many grapes to buy a giraffe.” Or consider how Brosh tells us about what she had to do to the 2-year-old who’s “apocalypse-level scared of dandelions”: “I trapped her under a towel and dragged her into the woods.” And, well, we get it.

Brosh has a distinctive way of making you laugh out loud one minute and hold your hands over your mouth with despair the next. In the title, solutions comes before, not after, problems, because nothing is resolved. Some things can’t be resolved because, as Brosh writes, “sometimes all you can really do is keep moving and hope you end up somewhere that makes sense.” From childhood kleptomania to divorce to mutually beneficial hostage situations to unfathomable grief and loss, Solutions and Other Problems may have felt like a long time coming, but it was well worth the wait.